What do Mohammad Ali, South Shields and Yemen have in common?

While making a film on boxing great's 1977 visit to a small UK coastal town, Tina Gharavi discovered something else

In 1977, in a typically flamboyant gesture, the boxer Mohammad Ali visited the unsung town of South Shields, near Newcastle, in the northeast of England.

Ali had been invited by one Johnny Walker, a local painter and decorator who knew the legend from his active boxing days, to help raise money for his club in the town. Astonishingly the three-time world champion agreed — touring the borough in an open bus to a rapturous reception from thousands of admirers. He played darts, sparred with a professional fighter and larked about in the ring with the local lads.

Then, the Western world’s best-known and most controversial follower of Islam staged a moment of pure theatre; he walked through the crowds to the small, rather nondescript Al Azhar mosque, where the marriage to his third wife Veronica was blessed.

The world might have forgotten that extraordinary day, but it is still talked about in the town. It, however, certainly came as news to Iranian director Tina Gharavi — whose latest film “I am Nasrine”, about a 16-year-old girl fleeing Iran after she has been assaulted, was nominated for a Bafta award in January — when she moved there as a lecturer in English (Digital Media) at Newcastle University.

“Ali was my hero, so I was really curious to find out more and make a documentary about his visit,” she says. “In the course of my research I used to go to the mosque to talk to those who met Ali as children and I came across these men from the Yemen. I discovered that there had been a population of Yemenis living there for more than 100 years. They had left their homes and settled here, and worked in the shipping trade and fought in the two World Wars.

“Many of them are now very, very old and I realised they would disappear, and their stories, which are absolutely fascinating, would be lost. I thought, someone has got to collate this.”

The result is an exhibition at the Mosaic Rooms, in West London, which combines a documentary on Ali’s visit entitled “The King of South Shields” with videoed testimonies from 14 of the men, the last surviving children of the first generation who settled in South Shields.

The testimonies are called “The Last of the Dictionary Men”, which is taken from a poem by Abdullah Al Baradduni that reads: “Our land is dictionary of our people, this land of far horizons where the graves of our ancestors sleep, the earth trodden by processions of sons and sons of sons.”

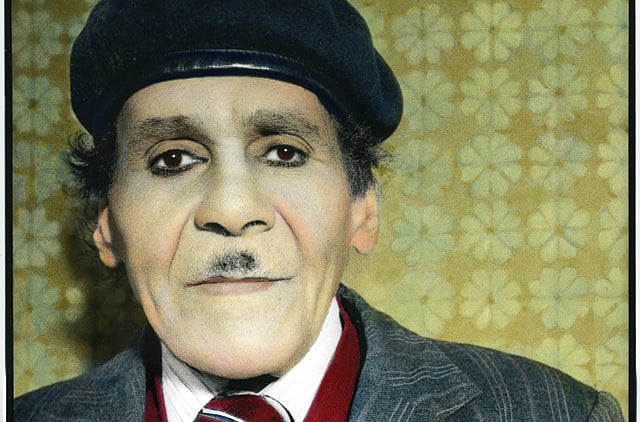

The gallery is lined with evocative original black-and-white photographs of the men which have been coloured by Egyptian Yousseff Nabeel, in the “Hollywood” style popular in the Cairo of the 1950s.

The Yemeni story is one of those curious accidents of colonial rule. In the 1890s, when the country was under British rule many Yemenis arrived to serve in the Merchant Navy. In 1909, the first Arab Seamen’s Boarding House opened in the Holborn riverside district of the town. Disputes over jobs led to race riots in 1919 but attitudes towards the Yemenis became more tolerant and there were no further major outbreaks of violence.

Many more were recruited during the First World War to serve in the merchant ships, and in the Second World War, about 700 of the 4,000 sailors from South Shields who were killed were Yemeni. By the end of the war, the Yemeni population had increased to more than 3,000, although, today, it has dropped to about 1,000. Many Yemeni sailors married local women and integrated into the community.

Just how integrated the town has become can be judged from the film which intercuts scenes of Ali on his visit with those of the Yemeni men going about their daily lives in the shabby streets and in their homes. The older men still wear their traditional headgear and the “thobe”, a long, often white, garment. We see them cooking up bowls of “asida”, a boiled flour pudding, and chatting away in Yemeni. The younger generation, on the other hand, are in jeans and T-shirts and talk with an odd mix of Arabic and Geordie, as the local accent is called.

“There is a boy in the film who was looking at Ali adoringly when he was in the ring,” Gharavi says. “He is still living in the town and I know that like many of the Yemeni he must have found it difficult to fit in. I understand that because I’ve had to fight a lot being an Iranian woman living the West. It’s a trouble with identity that gives you anxiety. You’re different and children don’t want to be different.”

She adds, “Despite the numbers in the town there was no trouble until the attacks of 9/11 when someone tried to burn down the mosque.

“The tragedy is that these guys have been such good British subjects. They have their history of being part of the war effort when Britain really needed them. They helped ensure that we beat the Germans.

“There is a Mr Obeya who I interviewed, who lost seven of his family in the war. What makes me so upset is that they are suffering because of the perceptions of Muslims and Arabs when in fact they have been model citizens, so loyal to their country.”

In his testimony Abdo Ahmad Mohammad Obeya turns out to be a talkative, colourful character in traditional headgear and dark glasses. In 1965 he got a British passport and left his village where he had been a farmer and owner of sheep, cows “and everything” to arrive one cold morning in South Shields not able to speak a word of English. He took a job as a stoker on the ships before being promoted to storekeeper and spent the years travelling to countries such as Russia, Canada, Latin America and Australia. Periodically, he returns to Yemen where he has ten children and a poorly wife.

“I was strong and worked hard,” he says on the video. “I liked overtime. I worked day and night.” And he adds proudly: “I learnt to repair machines. Yemenis are clever. You only have to show them once.”

Has he seen changes to South Shields? There is a poignancy about his answer, given in the short sentences, that shows his lack of fluency even after 47 years.

“We ourselves have changed. I am sick and old. The youth are different. The young see us as old-fashioned. The new generation don’t want us. Sometimes our sons don’t like us. The same goes for South Shields.”

They all seem to be ambivalent about where they truly belong and where they would prefer to end their days.

The mosque is the centre of their lives as it would be back home, and one of the old men talks about the “brotherhood and love between us”. None seem to have shaken off their Yemeni roots but all admire their adopted country. They all seem to agree on how much they appreciate the security that the law gives them and the freedom they have to practise their religion.

As one put it: “Whether black or white, Muslim, Jew or Christian, the law protects us and gives us a sense of order.”

But even then, he admits: “I am British citizen. But I have Yemen in my heart.”

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.

“The Last of the Dictionary Men” will run at the Mosaic Rooms, London, until March 22.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.