The play that shall not be named

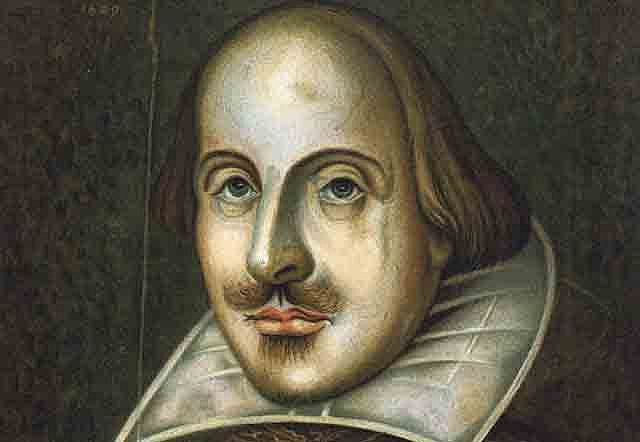

Even today, superstitions among stage actors abound and several have come to be associated with certain plays by William Shakespeare

Dubai: Don’t wish an actor good luck on opening night.

Instead, says Anthony Tassa, associate professor of theatre and performing arts at the American University of Sharjah (AUS), tell him or her to go out there and break a leg.

Stage actors, Tassa explains, are superstitious, and one belief holds that wishing an actor good luck on opening night is tempting fate. In Shakespeare’s time, Tassa says, to “break a leg” literally meant to bow by bending at the knee. Only those actors that had in effect done their job well were entitled to “break a leg” on stage to the applause of the audience, so by telling an actor to do so, one is actually wishing them good luck.

Such superstitions among stage actors abound and several have come to be associated with certain plays. However few plays keep actors on edge in quite the same way as Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Ever since it was first produced in the early 1600s, Macbeth has been the stuff of dark dramatic legend, held responsible for an array of theatrical misfortunes. Thespians have been said to have sustained critical injuries, become deathly ill and even died on opening night.

With a history of theatrical disasters in its wake it is not surprising that stage actors are wary of this play. In fact, one of the oldest theatre superstitions – known as the Scottish Curse – dictates that speaking the very name of the play inside a theatre will bring bad luck, an exception being when the name is spoken as a line in the play.

Thus actors refer to the play by euphemisms such as the “Scottish Play” or the “Bard’s Play.” Variations of the superstition also forbid direct quotation of the play except during rehearsals inside the theatre.

Tassa himself often honors the tradition, though not the superstition, when he discusses the likelihood of AUS producing the play.

“There is a very strong possibility that AUS theatre will be staging the Scottish play in Fall 2011,” he notes. “We are in discussions at present to have the title role played by a guest artist who happens to be a very important Arab film actor, but cannot announce anything until all decisions are finalised.”

Tassa, though himself not a believer in the curse, admits that he has seen his fair share of theatrical misfortunes when working on productions of the play.

“I have worked on five productions of Macbeth to date as both an actor and director, and every time something or the other just had to go wrong,” he recalls.

The first time something strange happened, he remembers, was during a rehearsal of the so-called Cauldron Scene in Act IV Scene I. Thirty minutes into the rehearsal a huge and completely unforeseen snowstorm hit and the cast were forced to leave lest they ended up getting snowed in the theatre.

The second time was in Florida when – again during the cauldron scene – a huge thunderstorm caused a blackout in the theatre, bringing rehearsals to an abrupt end. Another time misfortune struck was when Tassa was playing the title role at Longwood University. On opening night the three washing machines used to clean costumes broke down one after another.

Such instances might get anyone to start believing in the reputed Scottish Curse, Tassa remains resolute in his belief that everything can be explained with proper reasoning.

There are many theatre superstitions, he explains, the roots of which lie in a desire to actually prevent onstage accidents.

“For example did you know that there is a superstition that warns you against whistling on stage?,” asks Tassa. “To do so they say brings bad luck. But what most people don’t know is that stage hands were originally sailors who communicated with each other by whistling.”

So some superstitions can be explained but what exactly is it about the Scottish Play that has earned it such a dark reputation among actors and directors?

Tassa says that the answer to that question lies in the aforementioned Cauldron Scene. It depicts three witches gathered round a boiling cauldron, chanting incantations to create illusions with which to lure Macbeth to his eventual destruction. Tassa explains that there has always been a fear amongst playgoers, ever since the play premiered, that Shakespeare used real witch’s incantations in his text; in response, angry witches supposedly cursed the play. That and the fact that shortly after the three witches are done with casting their spell, Hecate – the goddess associated with magic, witchcraft and necromancy – enters the scene to congratulate the witches on their work.

Tassa reveals that such was the hysteria caused by that particular scene that the spectators actually ran out of the theatre for fear of the curse descending on them. Also not helping matters was the fact that fires often broke out in theatres during this scene. But once again Tassa is quick to point out that the fire had less to do with any curse or superstition than it had to do with the state of the theatres and how special effects were created during that time.

“Most theatres at that time were made out of wood and had thatched roofs. Couple that with the fact that gunpowder was used to create special effects like lightning and thunder and it is not surprising that a lot of theatres went up in flames,” Tassa says.

History

Dr. Fawwaz H. Jumean, head of Department of Biology, Chemistry and Environmental Sciences) at AUS, suggests that the reasons the play earned its dark reputation actually lie in the bloody history of the royal family and Shakespeare’s very motivation to write the play.

Jumean notes that Shakespeare wrote the play mainly to please James I of England, and drew heavily from the history of the royal family. Prior to being crowned King of England after Queen Elizabeth I’s death, James I was James VI of Scotland. His mother, Mary Queen of Scots, was forced to abdicate the Scottish throne in his favor, and was later executed for treason.

“To understand Macbeth one must understand the motive of Shakespeare. We must remember that Shakespeare, more than any other playwright, knew well his audience and was adept at capturing their attention,” Jumean points out.

When writing the play Shakespeare had two goals in mind, Jumean adds. He wanted first and foremost to please the newly crowned King – what better way to do so than by writing a play about a King of Scotland? Secondly, Jumean says, Shakespeare wanted to reassure James with a portrayal of himself as a legitimate monarch. Thus a major character in the play is Banquo, whose descendants were the Kings of Scotland, James among them.

Jumean observes that Shakespeare knew James I to be very superstitious. In 1579 James I had published a book titled Daemonologie, a compendium of learned dialogue, wherein he expressed his awe at witches’ power to manipulate individuals’ will. Shakespeare was also well aware of James’ fascination with the Malleus Maleficarum or the witchcraft manual as it is more popularly known today. Having known these factors, Jumean explains, eventually led to the creation of the cauldron scene in the play, which was in itself unnecessary to the development of the plot.

But both Jumean and Tassa hold that the play’s dark nature can also be attributed to Macbeth representing certain aspects of human nature.

Jumean notes that the play “reminds you that there is a certain degree of darkness within us all. Greed and the quest for power are present within everyone. It’s just that in those times it was easier to attribute them to witchcraft. However, unlike Shakespeare’s other tragedy, in which he injects a degree of opacity into the motives behind the actions (or in the case of Hamlet, inaction) of his main characters, the motives behind the actions of Macbeth are transparent. They are human, real and thus they intrigue and haunt us.”

“It does offer you a valuable warning against unbridled ambition does it not?” Tassa asks. “And it also makes you wonder what you would have done had you been in Macbeth’s position. Would you have allowed the witches to control your end? Or would you have fought against the lust for power?”

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2025. All rights reserved.