Tracking the Mears years

Bushcraft king Ray Mears can survive in the wild and track wolves, but his greatest challenges have been closer to home

Survival expert and naturalist Ray Mears admits that he’s always been a loner. It’s not that he’s unsociable, but he’s happy on his own in the great outdoors.

“I remember walking across an open space where people were playing cricket and somebody shouted out, ‘There’s the local hermit’, and I was quite proud. I thought it was cool. I don’t get lonely,” says the man who has fascinated millions with his bushcraft techniques on TV and through the courses he runs across the globe. “Looking back, I think I strolled into the woods one day and nature saw me and said, ‘Walk this way’.”

It’s now 30 years since he founded UK-based Woodlore, The School of Wilderness Bushcraft, where he teaches his unique skills and also arranges expeditions to places like the Arctic and Namibia. He can carve a canoe or a spoon, start a fire without matches, make a shelter of snow or sticks and track a wolf.

“The jungle feels like the nettle patch at the end of the garden and the desert feels like the rockery. Recently, I was in the desert looking for rattlesnakes and scorpions, but that’s just normal for me now.”

Even as a young boy growing up in Surrey, Mears had a quiet confidence. When he took up judo he learnt about the meeting of mind and body, and being in control of them. “It teaches you to have spirit and determination and not to give in. Judo always teaches humility and a range of traits that are incredibly valuable in life.”

Over the years his ability to survive has been tested to the limits, from encountering snakes and other venomous creatures in the Honduran rainforest to narrowly escaping death in a helicopter crash while filming in the US.

All this is charted in his new autobiography My Outdoor Life. But nothing could have prepared him for the most emotional and traumatic event of his life – the death of his beloved first wife, Rachel, who died from breast cancer in 2006, two years after being diagnosed.

They’d been together for 15 years and Mears, 49, admits that it was incredibly hard to write the moving chapters about her deterioration and his struggle to cope.

After she had a mastectomy, she was told the cancer was terminal.

“I heard the words coming out of the consultant’s mouth but they didn’t compute. It was like having one of those out-of-body experiences people talk about; like I was watching this from afar and it was happening to somebody else,” he writes.

Going against his nature

The trauma temporarily damaged his eyesight and he recalls that Rachel’s decline was as painful to witness as it was rapid. “It was very difficult to write,” he says now. “It was like reliving it. Doing an autobiography is a very stressful process, because I don’t really like talking about myself, and what is past I try to put behind me. I always move forward in life.

He says Rachel’s death changed him in many ways. “It makes you more sensitive to emotional stimuli. Moving movies are more likely to upset me.

“But the most profound effect it’s had is that it has made me intolerant of wasted time.”

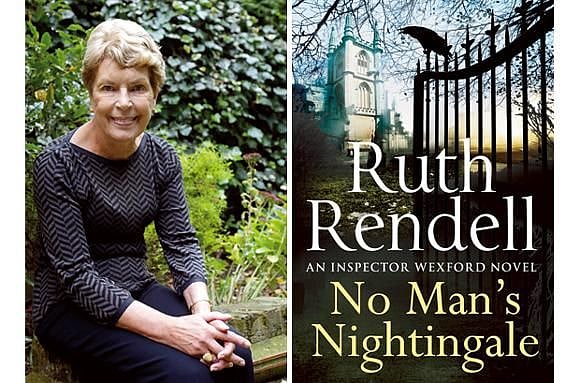

At first, he couldn’t imagine ever meeting anyone else, but 18 months after Rachel’s death, Mears met Ruth at a book-signing. She was a mature student reading archaeology at Durham University.

“I’ve no idea how, but she broke through the fog that had been surrounding me. It was love at first sight,” he recalls.

They went on to marry. “Ruth is part of the new me. I’m very lucky to have had a second chance.”

The son of a printer, Mears spent his first two years of life in Lagos, Nigeria, where his father’s work had been, before the family moved to Kenley on Surrey’s borders.

It was there that his love of nature came into its own, and on leaving school he went on expeditions with volunteering charity Operation Raleigh, before joining World magazine as a photographer, later founding his company, Woodlore. When his bushcraft talent was honed for TV, he discovered his newfound fame inevitably led to a loss of privacy.

“That’s the price you pay,” he reflects. “But for me, it was worth paying because I believe in what I do, and want to bring it to a wider audience.

“I hadn’t realised how widely it would take off and that the programmes would be shown worldwide.”

Real-life murder mystery

The hardest job he’s ever had though, was helping police track murderer Raoul Moat, who’d gone on the run following a killing spree in Northumberland in 2010.

“The stakes were so high. I didn’t seek glory or charge police for my time or expenses. I have a unique skill and was in a unique position to help.

“For 10 years I’d been teaching British special forces how to survive,” he continues, “so I have a good understanding of what happens to people when they try to do what he [Moat] was trying to do.”

In the more comfortable world of TV, Mears has just finished filming a series in America on the Wild West for BBC Four, which will go out next year, but says he doesn’t watch survival shows that create a false sense of jeopardy within the programmes for entertainment’s sake.

“I try to bring people and nature closer together. In the digital age, it’s more important now than ever before,” he adds.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2025. All rights reserved.