The quarter per cent rate rise by the US Federal Reserve was almost a non-event in global financial markets. This much anticipated policy move had already been priced in by the asset markets, both in the developed and developing worlds and reactions from the markets have shown that.

Stock markets globally made gains and the emerging economy currency markets welcomed the news. As such, Janet Yellen, the Fed chairperson, has been successful in implementing a major policy change because no damage has been done to the world economy as a result.

Of course, real success will be judged against the longer term performance of the US economy under higher interest rates. I do not think the global consequences of US monetary policy is going to be, as some Federal officials emphasised yet again, of much concern for Yellen and the US authorities in evaluating the success or the failure of the rate rise.

But it should, because in our highly interconnected world the US cannot continue to make monetary policy decisions solely based on a limited number of US macroeconomic indicators like unemployment and inflation. Also, not everyone in the US is convinced that the reported low unemployment rate is a reliable figure in measuring the health of the labour market and the economy.

The US economy still runs on huge household debt and not on high wages or investments in productive capacity. Therefore the benign immediate reaction from the financial markets to the rate rise only reflects its impact on the money managers’ short-term risk-and-return calculations.

Financial markets are no longer a good gauge of either longer-term health of the real economy or stability of financial markets. In the short-term, the latter will be a major concern for the Fed in this new world of higher interest rates.

Therefore, Yellen was extremely careful in her wording of the rate rise to assure financial markets that this is not going to be followed by sharp successive rises. Her comrades who head the central banks of major economies supported her assurances by announcing publicly that they are not going to follow the US in interest rate policy.

Different routes

Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, made it clear as a bell that the UK would not follow the US route for quite some time. The Bank of Japan announced that its injection of liquidity into the economy will continue and that it considers purchasing even more and riskier assets from banks to keep its interest rates low.

The European Central Bank too is looking for more innovative ways of supporting the Eurozone economy by keeping rates low for a long period of time. Of course these policy announcements do not mean that the currency markets could be kept under control when US interest rates diverge from the rest of the world.

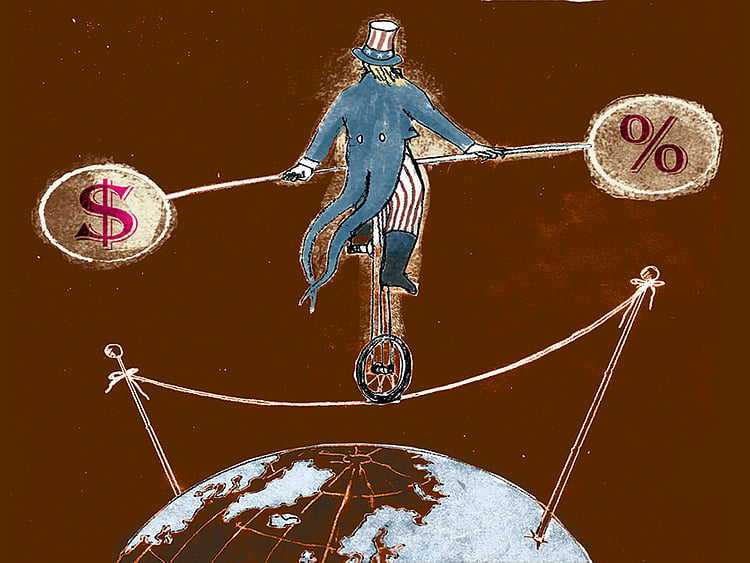

So there is going to be a rough ride for central banks in balancing stability in the financial markets and achieving macroeconomic objectives.

In this new world of slightly higher US interest rates, there would be two immediate major issues to deal with by the US and the rest of the world. The US concern is what the Fed will do with the $2.5 trillion (Dh9.2 trillion) worth of Treasury securities and the $1.8 trillion worth of mortgage-backed securities sitting on its balance sheet as a legacy from the low interest rate period.

To support its low rate policy the Fed needs to sell the securities on its balance sheet back to the financial markets. It has been experimenting with new methods to achieve this. The success of the new methods to reduce the size of its balance sheet will be as important as, if not more than, making interest rate policy announcements in the future.

The Fed can announce policy rates, but there is no guarantee that it will be able to control the pricing of credit risk and liquidity in the US financial system when it starts reducing its balance sheet. There is now increased risk of financial instability in the US economy.

Emerging economies

The second major issue concerns how the rest of the world will adjust to higher US interest rates. With Brazil going through one of the worst economic periods in its history, low commodity prices hurting many emerging economies and the Eurozone and Japan suffering deflation, the global economic growth will not get any support from the US monetary policy.

But this is a more realistic situation. The extraordinarily accommodating monetary policy in the US has created a fantasy world since the 2007 crisis. It is time now for the world and the individual countries to look into the face of structural economic problems that they have so far postponed dealing, rather than debating whether dollar interest rates should go up or down.

The writer is with Manchester Business School.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2025. All rights reserved.