Western critics of Russia’s Sochi Winter Olympics have picked up too much speed and risk skidding off piste. A justifiable attempt to scrutinise the government of President Vladimir Putin has degenerated into an exercise in schadenfreude and ill will. Politicians who have decided to attend the games (including China’s President Xi Jinping, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Turkey’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan) have been level-headed. Those who have ostentatiously stayed away — the UK’s Prime Minister David Cameron, President Barack Obama of the US and France’s President Francois Hollande — are following what the critic Harold Rosenberg once called “the herd of independent minds”.

Media interest in the alleged corruption around Olympic construction has been obsessive. The Washington Post describes the various projects as “Stalinist excess”. At a January press conference, Putin set the cost of the games at 214 billion roubles (Dh22.8 billion) and said related infrastructure ran far higher. Western sources estimate the whole project at $51billion, with some claiming a third of it was improperly diverted. That is a lot. But it is a local story: a Moody’s report last week described the credit impact on Russia’s companies as “mixed” and on its sovereign debt as “neutral”. Nor is Sochi a unique moral blot. The Salt Lake City Winter Olympics of 2002 were marred by a major corruption scandal and the Beijing summer games of 2008 were a more appropriate venue for protests about human rights.

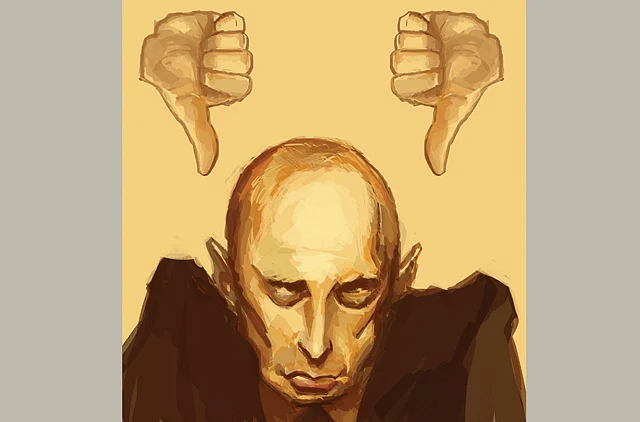

Certainly Putin’s respect for the democratic process has been fitful at best. Political opponents have been arrested and jailed throughout his time in office, even if several were released in December. He cracked down on a peaceful demonstration in May 2012, and eight of those arrested are still facing trial. Such conduct merits scrutiny, even if an Olympics is not the best forum. Of course, Putin did not come out of nowhere. “As a result of the Yeltsin era, all the fundamental sectors of our political, economic, cultural and moral life have been destroyed or looted,” wrote Alexander Solzhenitsyn in 2000, after Russia spent a decade following western advice. “Will we continue looting and destroying Russia until nothing is left?” Putin, who won an election that year, was Russia’s way of answering no.

Putin’s detractors have paid less attention to this history than to a short list of causes beloved of western elites: the EU, free trade, gay rights and Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the oil tycoon Putin jailed a decade ago and pardoned in December. Recently hundreds of writers, including Salman Rushdie, published an open letter in the UK’s Guardian newspaper deploring a Russian law against “so-called gay ‘propaganda’” (the actual text of Article 6.21 forbids promoting “non-traditional sexual relations” to children) and another against blasphemy. “As writers and artists,” the petition ran, “we cannot stand quietly by as we watch our fellow writers and journalists pressed into silence or risking prosecution and often drastic punishment . . . .A healthy democracy must hear the independent voices of all its citizens.”

Spirit of censorship

But “stand quietly by” is what many of these writers did when the UK’s Labour government passed a blasphemy law just eight years ago (the Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006), at the behest of some of the very groups (including the UK Action Committee on Islamic Affairs) that tried to ban Rushdie’s novel, The Satanic Verses, in 1989. That the UK House of Lords added amendments limiting the law’s reach does not change the spirit of censorship in which the bill was advanced.

Western commentators complain that performance artists of Pussy Riot, now touring the US, were arrested for disrupting a religious service in Moscow with what The New York Times calls an “anti-Putin song” and the band members call “a fun song”. Too bad they did not take advantage of the air of freedom to sing on US TV the scatological “prayer” they sang on an altar in front of worshippers two years ago.

There may be an unwitting tribute to Putin in the intensity of his detractors’ rage. Those countries lecturing him about “healthy democracy”, as Rushdie et al put it, have lately shifted power from legislatures to executives and from voters to bureaucracies.

In Europe it has been done through delegations of power to the EU. In the US, it has been done through judicial reversals of democratic election results (including on gay marriage) and congressional abdication (on trade, warfare, healthcare and intelligence gathering).

Putin presents himself as a defender of sovereignty, an example to those who do not wish to be forced to submit to the ways of Washington and Brussels. Western societies remain more liberal and democratic than Russian society. But the difference is not quite so obvious as it was 10 years ago.

— Financial Times

Christopher Caldwell is a senior editor at The Weekly Standard.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2025. All rights reserved.