Band Baaja Baraat turns 15: Ranveer Singh’s debut, Anushka Sharma’s vibrance and a romance Bollywood lost

Where did the days of real, grounded fun in Bollywood films go?

“Tere bin kissi cheez mein mauj nahin hai. Na chai mein, na chowmein mein…”

(Without you, there’s no fun in anything. Not in tea or chowmein).

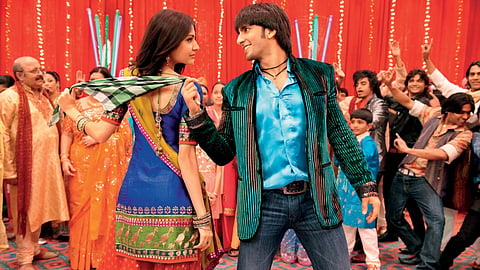

A rather repentant Bittoo (a debuting Ranveer Singh at the time) confesses this to his wedding planner partner Shruti (Anushka Sharma, also in her debut), after she verbally raps his knuckles for assuming he’s entitled to her love. It’s a kind of love admission that feels almost extinct in Bollywood today: fresh, innocent, disarmingly simple.

Bittoo just says what love really means to him. To him, love is being praised and acknowledged for doing good work. It’s feeling at ease with someone. It’s finding joy in the everyday — tea, conversation, the mundanity of shared silences. “If this is what love is, then that’s what I want,” he says, defiantly and without flourish.

It has been 15 years since Band Bajaa Baraat, and Bollywood’s romantic imagination has shifted dramatically. Love stories are no longer its default currency, routinely sidelined in favour of chest-thumping spy sagas and gritty crime thrillers. When romance does arrive, it often feels like an afterthought—or worse, a throwback in the most regressive sense.

Take Harshvardhan Rane’s Deewaniyat. A love story that leans heavily on dated ideas of obsession and entitlement, it feels less like a revival of romance and more like a reminder of how easily Bollywood slips backwards when it tries. And yet, it works. The film finds an audience, suggesting not approval of its politics, but something more unsettling: a hunger for love stories so acute that viewers are willing to accept whatever version is offered, however poorly imagined.

That hunger is hard to miss. Saiyaara crossing Rs 500 crore globally makes the point plainly—even as the film problematically muddles post-traumatic stress disorder with Alzheimer’s, audiences show up, dewy-eyed and hopeful. The message is clear: people still want romance. They just aren’t being given enough good ones.

Meanwhile, films like Jab We Met and the adrenaline-fuelled romance of Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani have been pushed into the safe, glassy cabinet of nostalgia, resurrected only through sequel speculation—discussions one hopes never materialise. Not because these stories don’t deserve revisiting, but because they belong to a time when Bollywood understood that love stories didn’t need spectacle or saviours. They just needed honesty.

In this nostalgic haze, Band Bajaa Baraat fits. With wedding bangers, (Ainvayee, hello)bread kaore ki kasam vows and ‘bijiness’, all set in the raw realism of West Delhi that had a personality of its own. Singh and Sharma’s debut film was built on a simple premise: a fiercely goal-oriented woman and a self-proclaimed loafer start a wedding planning business. The business thrives. Their relationship doesn’t. A crucial misunderstanding following a night of passion drives them apart. Shruti realises she’s in love; Bittoo insists he isn’t — and is visibly unsettled by the possibility that she might be. When Shruti reassures him that she isn’t, his relief turns into ecstasy. That ecstasy, in turn, pierces her. And so, she ends the partnership.

Of course, the love story has a happy ending—but not without a harsh confrontation. Bittoo is forced into a reckoning, a reality check that feels almost extinct in today’s Vanga-Animal–Kabir Singh era, where pulsing, angry men are allowed to be relentlessly aggressive, only to be miraculously redeemed at the very end, after a catalogue of inexcusable behaviour. Kabir, perpetually hot-headed, creates a scene at every turn and repeatedly resorts to the character assassination of his girlfriend, Preeti. He still ends up with her.

In the time of Band Bajaa Baraat, however, there was at least a clearer sense of acceptable flaws—and firm deal-breakers. The woman wasn’t expected to save anyone. The man had to figure out his own feelings.

Bittoo’s entitlement gets the better of him when he audaciously snatches Shruti’s phone, convinced that her decisions revolve around proving something to him. He is promptly sent away with a flea in his ear. Redemption here doesn’t require grand gestures or prolonged suffering. It’s realisation, followed by accountability—and a quick reconciliation.

And the film never tried to position itself as a game-changer. It promised little, yet delivered so much. Even its aesthetic choices reflected this grounded honesty: Sharma’s bright kurtas and neatly tied dupattas in Ainvayee mirrored Delhi’s middle class, a far cry from today’s parade of slinky blouses, skirts, and perpetually half-buttoned kurtas.

Where did this Bollywood go? Why do its softness, its songs, and even its clothes now exist largely in memory, while we’re left contending with loud, interchangeable clichés that look suspiciously like the film before them?

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox