Is there anything on earth more indulgent and sumptuous than letting a piece of rich, dark chocolate roll over your tongue? With its complex flavours and aromas, it is a sensation that to this day constantly calls for revised descriptions.

From the moment when Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés revelled in the unusually bitter cacao drink in Montezuma's court in 1519, this classic delight has become a culinary coup d'état in the European quest to master the processes of preparing this exotic bean.

But who could have foretold the extent to which the humble South American cacao bean (Theobroma cacao) would fuel global infatuation, stoke fierce culinary competitions and create a cult of connoisseurs who incessantly debate the finesse of its methods of production?

Europeans were initially sceptical when they were first presented with the bitter cacao beverage from an unknown land, causing superstition to shroud the curious bean. They nevertheless saw the potential for experimentation and consequent monopolisation.

Despite the discovery of the first cocoa bean then, it was a few hundred years before chocolate as we know it was produced. It made its grand entry into the homes and parlours of bourgeois Europe as a drink similar to the bitter product in South America, infused with honey and herbs.

It wasn't long before confectioners became intrigued by its prospects and soon they were adding sweeteners such as sugar and vanilla to make the product more palatable. Cacoa became coveted, its flavours and processes were sought to be perfected in a cut-throat industry of rival confectioners. Chocolate meant exclusivity, which translated into a money-making enterprise given its reservation for the wealthy.

Intrigue in its magical properties was cultivated, and it wasn't long before physicians began to propose its myriad health benefits, fuelling the fascination further.

The allure of experimenting with the bean drew confectioners from far and wide, and so the term ‘chocolatier' came to be. In 1788 the first chocolate press was produced by Doert, a Frenchman. From that time chocolate-making gained momentum.

Dutchman Coenraad van Houten discovered in 1828 that when the fatty matter (cocoa butter) was separated and removed, the leftover mass could be ground into powder. This was not entirely unheard of, since the Aztecs had added wood ash to achieve a similar by-product centuries before. Van Houten patented the revolutionary wooden screw press as a result of his discovery.

The process of separating cocoa butter was hence termed ‘Dutching' and alkalised cocoa (or European-style cocoa in other countries such as the US) was coined. Dutching allowed chocolatiers to achieve a milder, less gritty taste. The hunt for the perfect means of production had begun.

Without a doubt, the majority of aspiring chocolatiers and confectioners flocked to Switzerland, which fast became the haven for chocolate pioneers. The sprouting factories in Switzerland declared the Swiss as the forerunners of the industry by the turn of the 20th century.

At the forefront of indulgence

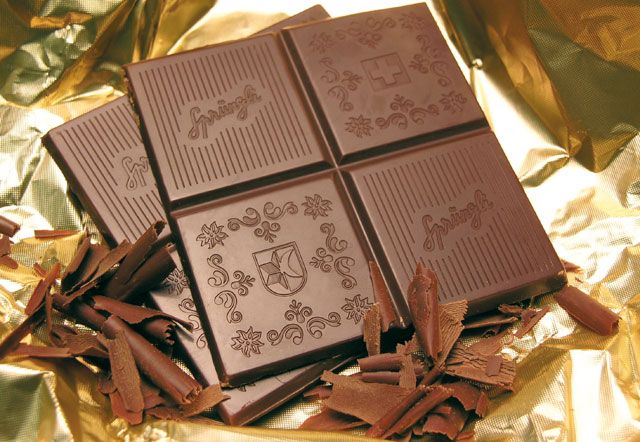

One such leading chocolate production house that cropped up during this time was Sprungli, which opened in 1836 when David Sprüngli and his son Rudolf established the Sprüngli and Sohn confectionery business in Marktgasse in Zurich. Today, Confiserie Sprüngli owns 17 shops throughout Switzerland. It is also considered to be one of the best places for budding confectioners to learn the trade.

The Maître Confiseur for Confiserie Sprüngli, Sepp Fassler, started in 1983 at Sprüngli as an apprentice. From his first day on the job, he says that he was passionate about chocolate. He is particularly passionate about cocoa beans from Callao Salvaje in Spain, called Criollo Al Salvaje. On a recent visit to Dubai after promoting the Swiss National Day celebrations in the emirate, Fassler discussed his lifelong passion.

He begins by explaining the difference between a chocolatier and a chocolate maker. "A chocolate maker produces the chocolate from the raw material - the cocoa bean. A chocolatier works with the finished product - chocolate already in existence," Fassler explains.

"The chocolate that was being made at the beginning of the 19th century in central Europe was not chocolate as we know it now. It was harsh and very bitter and was not as smooth as the chocolate produced today," he says.

A crucial discovery was when confectioners realised that chocolate could be melted with milk and cream at a very controlled temperature. That was the moment when Swiss chocolate began its success as a forerunner in the industry. Prior to this discovery, many people did not like chocolate - it was very much an acquired taste.

It was no small coincidence that the son-in-law of the famous Rudolf Lindt discovered the milk combining process. Lindt was the one who refined the process of chocolate making when he discovered ‘conching'. Conching is the process of moving the chocolate mass about at a controlled temperature. "Through this kind of massage, the bad aromas are released," says Fassler.

"The fineness of the chocolate improves through conching and the grittiness is done away with. Basically, the finesse of the chocolate improves."

From processing to palate

In Switzerland, chocolate makers still use the same machine that Lindt used when he invented it. In technical terms, a conche is an agitator that evenly distributes cocoa butter within chocolate, and may act as a polisher of the particles. It promotes flavour development through frictional heat by releasing volatiles. There are numerous conch designs. Food scientists are still discovering precisely what happens during this process and why.

The word arises from the shape of the vessels initially used, which resembled conch shells. Legend has it that Lindt mistakenly left a mixer containing chocolate running overnight, and though he was initially distraught at the waste of energy and machine wear and tear, he realised that he had made a major breakthrough. Lindt's invention rapidly changed chocolate from being mainly a drink, to bars and other confections.

The chocolate mass spends 72 hours in the conch. "This is an expensive procedure because nobody wants to invest three days," says Fassler. Thus the machines have become more developed to do the job quicker and with less labour. I can say that a good chocolate needs time - to make and to work with - for the end product to be truly appreciated and enjoyed," he says.

Tempering is the process of moving the cocoa mass and this is how cocoa butter is prepared. "When you work with chocolate, it naturally has to be in its liquid form," explains Fassler.

There are set steps to tempering. "The first is to melt it at 45˚C," says Fassler. "You move the mass constantly so that it doesn't separate. The crystals of the cocoa butter build while heated at this temperature.

The temperature is then lowered to 32˚C, breaking down the cocoa butter's sugar crystal structure. It has to be a very specific consistency - more like dough than liquid. The temperature has to be controlled at 32˚C for a certain length of time to achieve a homogenous, silky glow and a clean break, which defines an excellent chocolate. It is a time-consuming process to get it to that perfect result. You should never stress the mass."

A growing culture

The quality of the cocoa bean also plays a critical role. The better the quality of the cocoa beans used, the finer the final product will be.

Refined chocolate makers are very selective with the cocoa they use. For example, at Sprüngli only Criollo and Trinitario cocoa is used. These beans - Criollos, Trinitarios, and some subspecies of Forasteros - are mostly imported from the tropical rainforests of West Africa, the Caribbean, Ecuador, Java, Madagascar and Venezuela.

The soils and climates in which they grow produce beans that yield the greatest nuances of aroma and flavour. In 2008, the cocoa harvest was 3.6 million tonnes. Three per cent of this was Criollo and 10 per cent were Trinitario beans. They are the rarest and most sought-after cocoa varieties. The rest is consumer cocoa, predominantly from the Ivory Coast.

Chocolatiers, quite simply, are like bloodhounds when it comes to cocoa. "Each cocoa bean has its own character," says Fassler. "We can clearly smell the difference between mass-produced beans and Crillio and Trinitario beans. The quality of chocolate is determined by the type of bean and the climate in which it is grown and produced."

Matters of taste

"There is a culture of appreciation surrounding chocolate in the same way that one can appreciate gourmet food," says Fassler.

Chocolate tasting clubs have become increasingly popular worldwide, particularly in Europe. "In Switzerland, we have a panel who define the differences between cocoa varieties," says Fassler. "It's a very exclusive board of chefs, cocoa connoisseurs and chocolatiers who are driven at ensuring that the highest quality of cocoa is used in Swiss chocolate."

Naturally, every chocolatier has their own ideas and selective tastes, but the panel presents a forum for discussion; there are no concrete guidelines.

"When you start working with cocoa mass, you can alter the taste by the length of time you conch the chocolate mass. But to think that the longer you conch the chocolate, the finer the product, is a grave misconception," says Fassler.

"There is a school of thought that believes that if you conch cocoa mass for a full 72 hours, it's too long, because the cocoa will have already reached its peak. I believe this to be true, so some chocolate producers have reduced our conching time to 60 hours. According to my tastes and my experiences and what I smell, the penultimate result is achieved after 60 hours. We believe that after 72 hours, the mass starts deteriorating."

Sprüngli general manager in the Middle East, Ester Crameri, adds: "The discovery and importing of the Grand Crux cocoa bean which began in 2003 changed the face of chocolate production even further. Prior to this, there were only milk and dark varieties. With this new line of dark cocoa, there is a whole new dimension to it. This brand of bean is less sweet and offers a fireworks show of flavours!"

People have become more sensitive to sweetness, particularly when one considers the rapid increase in diabetes, says Crameri.

"There is no such thing as sugarfree chocolate, except for those varieties which include alternative sweeteners. But with really dark chocolate, the sugar content is lower because there is more cocoa in this variety, making it a lot healthier for you."

Couverture chocolate is made with the best beans and is therefore of the highest quality. It is ground to the finest particle size and has a higher cocoa butter content. These qualities enable it to be used for delicate work. Very dark gourmet chocolate is 65 per cent cocoa, while milk chocolate has 37 per cent. But in industrial dark chocolate, the cocoa content only measures at around 40 per cent and in milk chocolate it is even less. The rest of the bar comprises cocoa butter and sugar.

Some schools of thought argue that ‘white chocolate' is not chocolate at all. All white chocolate is sugar, cocoa butter and milk powder; the cocoa mass, the essence of ‘true chocolate' is missing. "A true chocolate lover will not eat white chocolate as there is no cocoa mass in it," says Fassler.

There is most certainly an element of snobbery involved in chocolate appreciation, agrees Fassler. "If we see someone go crazy for white ‘chocolate', we shake our heads, bemused by their ignorance." The debate rages on as to what constitutes good chocolate, and what processes produce the best result. There's no one answer.

"I can say that Swiss chocolate, when compared to other varieties, is world-renowned for its smoothness," says Fassler. "We defined smoothness by patenting conching and it's evident hundreds of years later by how our chocolate melts in your mouth. I don't like to compare one chocolate brand to another. I prefer to focus on the way we make chocolate and on achieving the best results," says Fassler.

Death by chocolate

Good chocolate. What is that? Sepp Fassler from Confiserie Sprüngli explains what defines good chocolate…

The type of cocoa used

The dedicated passion put into the process

The ‘knak' of the chocolate, which is the sound heard when you bite it. "It must be a clear crack," he says.

The smoothness, which is measured by how it melts in the mouth.

The taste on the tongue

The fresher the chocolate, the better it is. In time, the flavours evaporate and it loses its brilliance, Fassler explains

The darker the chocolate the better: the higher the cocoa content, the less the sugar and artificial additives and ultimately, the better it is for you

Good for you

Chocolate is good for circulation. Dark chocolate has been found to have a high level of antioxidants, specifically from its flavanol content. "Of course, like all things, it should be taken in moderation," advises Fassler. It is considered to be a largely psychoactive food.

Studies show that verbal and visual memory are increased by eating chocolate. Impulse-control and reaction-time are also improved.

A symposium at the 2007 American Association for the Advancement of Science presented evidence that chocolate consumption can also be good for the brain.

Experiments with chocolate-fed mice suggest that flavanol-rich cocoa stimulates neurovascular activity, enhancing memory and alertness.

So the next time you feel guilty for indulging in that wickedly delightful slab (providing it has high cocoa content) relax a little… it's all in the name of brain food!

Why is Switzerland renowned for its chocolate?

"In Switzerland, we're raised in an environment of chocolate appreciation," says Fassler.

"Our palates are trained from a young age and are as result, naturally very refined when it comes to chocolate tasting. As an example: when Lindt relocated one of the chocolate factories to Germany, there was an outrage, because connoisseurs all over were saying that the chocolate was not that same. This is because the milk and the cream used - as well as the climate - differed. Swiss people eat so much chocolate that they realised the difference. It's an intuition we grow up with," says Fassler.