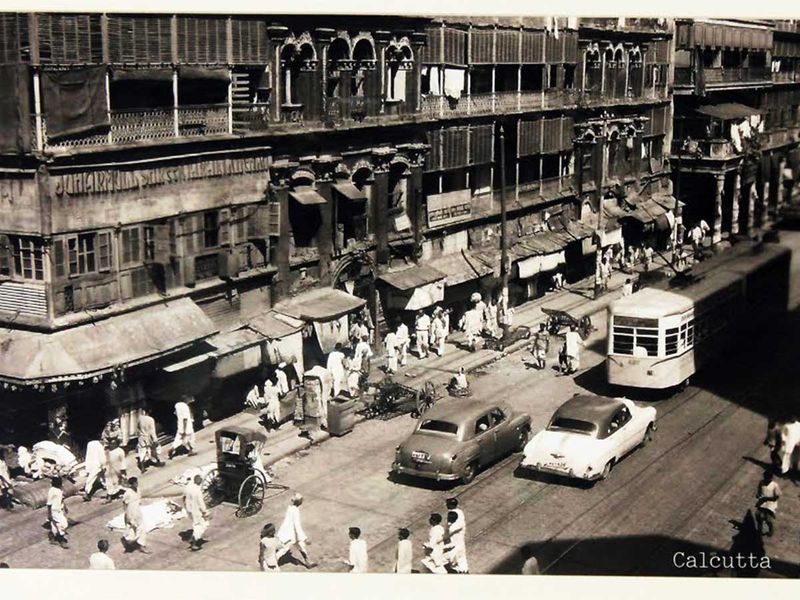

Kolkata: The tram rattled along College Street, passing dozens of book stalls and announcing itself with the quaint chime of a bell. A gentle breeze from its open windows and antique ceiling fans cut the humid summer heat.

Sounds and smells from the streets wafted in - fresh fish splayed out on the sidewalk, the muezzins’ call to prayer - as the tram passed vegetable wagons and ornate colonial buildings.

“You get all the flavours of Calcutta here, so it’s the best way to travel,” said a medical student, Megha Roy, riding the tram with two friends. She used the Anglicised version of Kolkata, which residents deploy interchangeably with its current spelling and pronunciation.

The three friends had jumped onboard spontaneously, with no clear idea of where the tram was going or when it was scheduled to get there. But it didn’t really matter. The ride itself was an unexpected treat.

“It’s like a fairy tale,” Roy said.

But in reality, Kolkata’s trams - the first in Asia and the last still operating in India - are in trouble.

In recent years, hit by natural disasters and official neglect, the city’s tram system has become little more than a nostalgia ride, its passengers more often looking for a lark than an efficient trip home.

And authorities say that while trams should remain a part of the transit mix, buses and the city’s metro system better serve 21st-century riders in the city of some 15 million people.

The tram system, built in 1881, was instrumental in Kolkata’s growth into one of the world’s most populous cities, cutting the path for the development of a metropolis on the move.

“We grew up as a city with the tramways,” said Aranda Das Gupta, some of whose earliest memories are of the tram rolling past his great-grandfather’s bookstore, which opened just five years after the tram first arrived. “It’s the heritage of Kolkata.”

A few committed riders are fighting hard to preserve that heritage.

Light rail

Pointing to cities from San Diego to Hong Kong, they say light rail is being reevaluated globally and argue that Kolkata’s 140-year-old system makes sense for a city struggling with pollution and overcrowding.

In an age of growing concerns about climate change, the emission-free trams, powered by overhead electric lines, are a better option than diesel-fuelled buses and private cars, activists say. The trams were briefly pulled by horses, an experiment that ended in less than a year after too many horses succumbed to the heat.

“Scientifically, economically, environmentally, there is no reason to convert the tramways for buses,” said Debasish Bhattacharyya, president of the Calcutta Tram Users’ Association.

But the scene at one tram stop suggested commuters may feel differently. Fewer than a half-dozen people were waiting for the tram, while nearby, hundreds were piling onto buses that sagged under the weight of so many passengers, belching black plumes of diesel exhaust as they careened over the tram’s tracks and onto the street.

Admittedly, neither speed nor punctuality are hallmarks of the trams, which must contend with a melange of traffic on their routes: trucks, buses, cars, vintage yellow Ambassador taxis, rickshaws manual and electric, pedestrians, herds of goats and the occasional cow.

“Nobody knows when the next car will come,” Bhattacharyya said. “They say this is the control room, but nothing is controlled; everything is scattered,” he said, gesturing to a hub of the tram system in central Kolkata.

Rajanvir Singh Kapur is the managing director of the public enterprise that oversees the tram and bus system. His office is perched on the third floor of the stately Calcutta Tramways headquarters building, little changed in outward appearance since the 1960s, when the company - now known as the West Bengal Transport Corp. - was a huge employer of organized labour that spawned some of the era’s powerful leftist leaders.

Kapur said Kolkata used to be a public transit-oriented city, long run by the Left Front, an alliance of communist and left-leaning parties that, he joked, made it into the Cuba of India.

But, he said, the city’s trams - a relic of the British Raj repurposed for a postcolonial era - “could not keep up with the pace of development.”

As a result, cyclone-battered electrical lines have gone unrepaired. Tracks have been dug up to build underground metro lines. And traffic police have canceled routes, saying the tram takes up too much space on Kolkata’s crowded streets.

Control room

Inside the tram system’s control room, employees worked the phones to coordinate trips. The system has become so haphazard that there is no longer a functioning timetable.

“At present, in my view, it’s dying,” said a control room officer who requested anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to reporters.

“Nothing is here. You cannot compare what we had with what we have now,” he said, looking out wistfully through the big picture windows at palm trees swaying over an active tram line - and an empty commuter parking lot.

Aboard a tram crawling along Lenin Sarani, one of central Kolkata’s main thoroughfares and named in honor of the Russian revolutionary, Sumit Chandra Banerjee, a ticket taker, said he looked forward to mandatory retirement when he turned 60 in October.

“Tram service is very poor, but once upon a time, the tram was one of the best,” he said, turning to pull a white rope to sound the bell for a stop. “Now, poor tram, poor service, the number of trams cut,” he said, crossing his forearms into an X shape.

Monthly tickets have disappeared, but at 7 rupees a ride - about 9 cents - it is still one of the cheapest ways to get around.

In the Shyambazar tram terminus, ticket takers, accountants and conductors escape the midday heat to drink tea in a room framed by portraits of Hindu gods and prominent Bengalis, like philosopher and poet Rabindranath Tagore.

While the tramways are no longer the mega-employer they once were, government jobs are still highly coveted in Kolkata and across India since the private economy has fallen short of meeting the great demand for safe and decently paid work.

Six tram routes remain operational in a system that used to resemble a bicycle wheel. Now most of the spokes have been broken off, leaving vast swaths of the city uncovered by tram lines.

But to preservationists, what’s left of the trams - as much a Kolkata institution as the universities the steel carriages trundle past, or the city’s cantilever bridge - must be saved.

“If they announce the discontinuation of tram service, there will be public unrest,” Bhattacharyya predicted.

So instead of any sudden shutdown of service, he argued that authorities are allowing the system to disappear quietly, by failing to make critical repairs.