The Hague: War crimes judges said on Thursday that a Malian militant was liable for €2.7 million (Dh11.58 million) in personal damages for destroying Timbuktu’s fabled shrines in 2012, as they ordered reparations in a landmark ruling.

The International Criminal Court ordered that the victims of the razing of the fabled West African city’s historic treasures be paid “individual, collective and symbolic” reparations.

But the judges at The Hague-based tribunal also recognised that Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi — jailed last September for nine years — was penniless, saying it was now up to the Trust Fund for Victims to decide how the outstanding amount will have to be paid.

The fund was created in 2004 by the ICC’s state parties with the aim of addressing harms resulting from genocide, crimes of humanity and war crimes.

It implements any reparations ordered by the court — including financial payments — and aids victims. Funding comes from public and private donors as well as court-ordered fines and forfeitures.

The fund now has until February 16 to come up with a plan how to implement Thursday’s reparations award.

Judges further ordered the Malian state and the international community be compensated with a symbolic amount of €1 each for damages suffered.

‘Terror and helplessness’

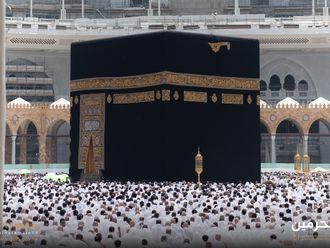

Militants used pickaxes and bulldozers against nine mausoleums and the centuries-old door of the Sidi Yahya mosque, part of a golden age of Islam after over-running northern Mali in 2012.

Timbuktu, founded by Tawareq tribes between the fifth and 12th centuries, has been nicknamed “the city of 333 saints,” referring to the number of Muslim sages buried there.

During a halcyon period in the 15th and 16th century, the city was revered as a centre of Islamic learning — but for 21st century extremist militants, its moderate form of Islam was idolatrous.

The assault on the Unesco World Heritage site triggered global opprobrium, but also led to a legal precedent.

Al Mahdi’s case was the first to come before The Hague-based ICC as a crime of cultural destruction.

He was jailed for nine years in 2016 after he pleaded guilty to directing attacks on the world heritage site and apologised to the Timbuktu community.

The destruction of the shrines carried “a message of terror and helplessness and destroyed part of humanity’s shared memory and collective consciousness,” judge Raul Pangalangan said.

“It renders humanity unable to transmit its values and knowledge to future generations,” he added.

Jailing Al Mahdi sent a strong warning that destroying cultural heritage would not go unpunished, and reparations will aim to “alleviate the lasting imprints” of the crime, Alina Balta at Tilburg University’s International Victimology Institute said.

Compensation question

According to the court’s 1998 founding accord, the Rome Statute, judges can determine that victims are entitled to reparations including “restitution, compensation and rehabilitation.”

The court can also hand out an order directly against a convicted person, demanding similar reparations.

Thursday’s award will now be closely scrutinised, given concern about whether substantial funds can be secured, and the time it will take to reach victims.

The security situation in northern Mali “poses serious challenges,” the Trust Fund for Victims has warned.

“The chamber notes the information received that the security situation in Timbuktu makes travelling there or contacting victims difficult,” the judges said.

Symbolic damages

The reparations will only be the second such award in the history of the court since it began work in 2002.

In March, the ICC awarded symbolic damages of $250 (€212) to each of the 297 victims of former Congolese warlord Germain Katanga, who is serving 12 years for a 2003 attack on a village.

The court estimated the damage caused in the attack at $3.7 million, and found Katanga liable for $1 million of that total — but at the time also acknowledged he was penniless.

Al Mahdi was a member of Ansar Dine, one of the Al Qaida-linked militant groups which seized territory in northern Mali before being mostly chased out by a French-led military intervention in January 2013.

The shrines have now been restored using traditional methods and local masons, in a project financed by several countries as well as Unesco.