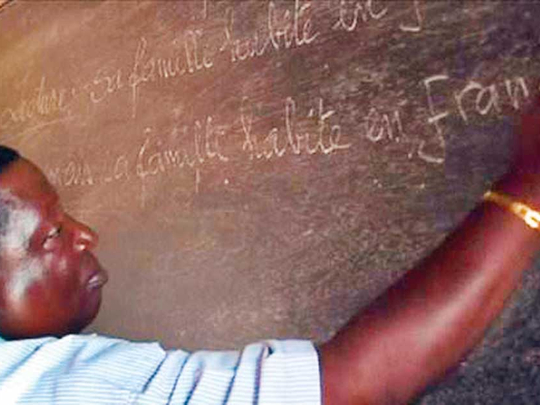

CANCHUNGO, Guinea-Bissau: The school year is ending in the West African nation of Guinea-Bissau, but some pupils will hardly notice the difference.

Long-running pay disputes have kept teachers out of the classrooms for long stretches of the last four decades in this former Portuguese colony, where a dysfunctional government struggles to provide basic services to its citizens.

The problem is so acute that despite widespread poverty, parents have launched an initiative to pay all, or part of teachers’ salaries directly, hoping their children will not miss out on more precious years in the classroom.

“We thought it was necessary to create a sustainable programme to try and give our children a year at school, asking for a contribution from each parent,” said Alberto Suleimane Djalo, head of the parents’ association at Ho Chi Minh high school in the northern town of Canchungo.

“We have around 150-200 parents who support us,” he added.

Local official Pedro Mendes Pereira described the Canchungo school community as heavily drawn from “impoverished” rural areas in the West African nation, who nonetheless began making payments “so that the teachers don’t go on strike”.

Teachers’ salaries are erratic if they are paid at all and drawn-out strikes are common in this small, unstable nation.

An ongoing government shutdown and, in previous years, a succession of coups d’etat have eroded the normal functioning of the state — and its ability to pay salaries.

Meanwhile, the country’s national parents’ association is experimenting with autonomous schools in the northern Cacheu and southern Quinara regions, setting households a monthly fee of 500 CFA Francs (75 euro cents) per child.

“We want to roll this out in every region of the country,” said Papa Landim, the president of the national parents’ group.

The refusal by many teachers to show up for work has also prompted innovative schemes by parents to help staff return to their place at the front of the classroom.

In the village of Eticoga on the distant island community of Orango Grande, six hours by boat from the capital Bissau, parents contribute five-kilogram (11-pound) sacks of cashews, rice, fish or palm oil, which is sold at market in the closest town or on the mainland.

The money collected is kept in a communal pot guarded by the village chief and used to pay the costs of a dozen teachers in charge of almost 300 children in the local area, as well as school maintenance.

“If we cancel our lessons and go back to Bissau, it would be very difficult for us to come back to work once the strike was suspended because of the remoteness of the islands and difficulties of transportation,” said primary school head teacher Joao Gomes.

“So we prefer to stay in the village and reach an understanding with the parents of the pupils,” he added. “There is trust, and that makes it work.”

The farmer and fishermen parents of Orango Grande’s schoolchildren are well aware that things are unlikely to change anytime soon after what UN education and culture agency, Unesco, has described as “40 years of institutional instability”.

The National Institute for the Development of Education (INDE in its Portuguese acronym) says just 30 per cent of the curriculum on average was completed in primary and secondary schools in the last 20 years.

And parents in a country, where the average citizen makes just $620 a year, according to the World Bank, frequently cannot make up the massive shortfall.

“Most of our classmates ended up leaving because they can’t pay,” said Eugenio Gomes, a pupil at the Ho Chi Minh school.

A Unesco report from November last year showed that Guinea-Bissau’s households nonetheless contributed 63 per cent of the country’s total educational expenditure.

Even taking into account the country’s “meagre” budget, the report said, the proportion earmarked for education was one of the lowest in Africa.

Against this backdrop, “life expectancy is 50 years, 70 per cent of the population live below the poverty line and 50 per cent of adults can neither read nor write,” it added, hindering the country’s development.

“Successive governments tout education as one of their priorities, but they don’t care if the teaching is of good quality or not,” said Braima Djalo, of the National Institute for the Development of Education.