Highlights

- At only 20 years old, Raymund Narag started spending the next 7 years of his life in pre-trial detention, with some of the Philippines' most violent criminals.

- Inside the notoriously crowded Quezon City Jail, he learnt about internal workings of the criminal justice system, and why cases drag for years.

- Through his work, Prof. Narag is now a recognised international criminology expert who aims to introduce positive changes to the criminal justice system in the Philippines and, through his students, the world.

In 1995, Raymund Narag failed to attend his university graduation. He was the valedictorian of his high school class. Within his first week as a freshman in the University of the Philippines Diliman campus, he joined a fraternity. And though he earned his university degree with honours he skipped the graduation ceremonies.

The reason: he, along with 10 others, faced arrest warrants following the death of another student from a rival fraternity.

7 years in detention

He spent the next seven years in pre-trial detention in the notoriously congested Quezon City Jail, living with some of the country’s toughest criminals.

“I saw first-hand the harrowing emotional and psychological impact of prolonged trial detention in overcrowded jail centres,” he told Gulf News.

A Regional Trial Court (RTC) eventually found him innocent of any crime. Narag, now 46, hails from Tuguegarao City in the Philippines’s northern Cagayan province.

He has gone a long way, having completed his PhD in the US. As assistant professor, he now mentors criminology students from different countries in America. He remains grateful for the experience. It shaped who he is today. “What happened was a blessing in disguise,” he said.

Life-changing experiences

The journey from tragedy to blessing was long. For a 20-year-old then, facing a warrant of arrest was crushing. “I was a grim-and-determined idealist. I was an atheist during my college days. I had a clear plan set for my life: Become a lawyer, practice law, run for congress in my province, then maybe, eventually, run for president… But God has a different plan for me,” Narag recalls to Gulf News.

His nearly 2,500 days in pre-trial detention marked by numerous delays did not destroy his inner grit. If anything, it stirred up a firm resolve to help improve the system — one inmate, one family, one lawyer, one judge, one institution at a time. He was determined to do something that would bring about positive change.

Life under detention

Life under detention made him a keen observer — and a doer. Narag used his leadership skills to organise peace and order councils among detainees. He taught fellow inmates, even wrote letters at the back of cigarette packs for them to their families — asking for forgiveness, even if the inmates didn’t say it. This helped break walls: reconciliation happens during the next family visit.

He taught fellow inmates, even wrote letters at the back of cigarette packs for them to their families — asking for forgiveness, even if the inmates didn’t expressly say it. This helped break walls: reconciliation happens during the next family visit.

“It felt like I was in a real-life school — in a prolonged immersion with fellow inmates. I tried to understand why riots, noise barrages and gang wars happen. How people end up in a life of crime,” he said.

Guidance, academic pursuit

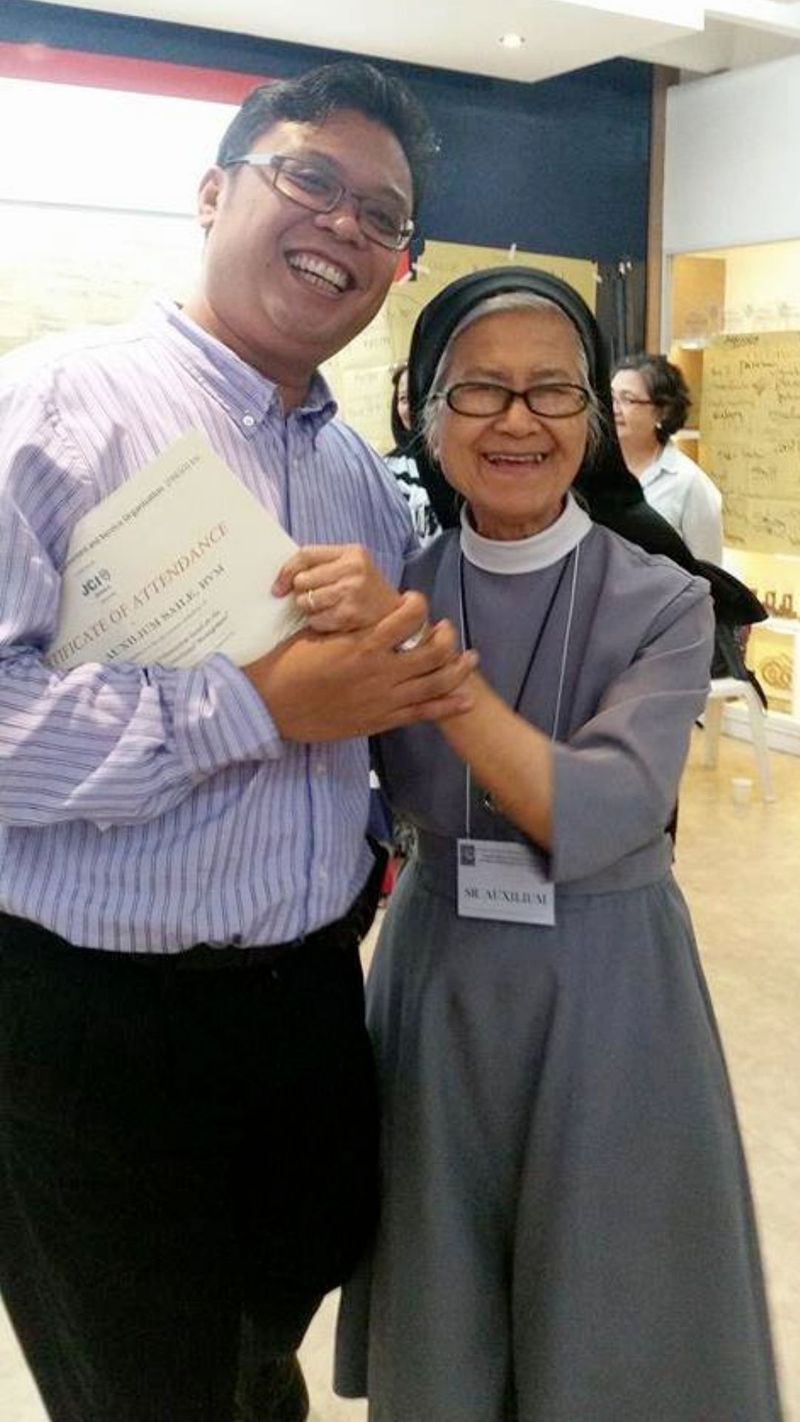

His detention, from 1995 to 2002, gave Narag much time to reflect on his life, too. While there, he found a personal guide in an elderly nun, Sister Auxilium Sayle who regularly visited them at the Quezon City Jail. “She told me: ‘To whom much God has given, much is expected.’ That stayed with me, till today.”

After his release, Narag worked his way through post-graduate school, completed his Masters degree at Michigan State University in East Lansing in 2007 and his PhD in 2013 from the same university.

In the process, he has conducted extensive studies on Philippine jails. It became his lifetime devotion — besides data-gathering, he conducts trainings for the officers of the BJMP (Department of Interior and Local Government), the provincial jails, the BuCor (under the Department of the Justice) and formed a foundation supported by judges to create a community bail bond system and help improve the administration of criminal justice overall.

From prisoner to professor

Recently, Narag was appointed associate professor in the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice in the School of Justice and Public Safety at the Southern Illinois University.

It's mix of grit and destiny. For the last 20 years, he has conducted extensive research, many of them funded by grants, with the Philippines’ Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP), the provincial jails and the Bureau of Corrections to help “persons deprived of liberty” (PDLs) get speedier trial, like the one he never had.

Digitising court calendar

To avoid delays in court hearings, he offered a rather simple solution. Narag has helped digitise a court calendar system — so all the parties are informed and reminded a day before a court session, thus avoiding unnecessary postponements. The courts have adopted his digital court calendar as “heaven-sent”.

Narag and his geek friends are now spearheading software development to turn the digital calendar system into an app that pings mobile phones of people concerned in each case with reminders.

Average: 529 days in detention

Data from his study of 6 Metro Manila jails suggest that persons deprived of liberties (PDLs) — people still presumed innocent, and in the process of determining guilt or innocence — stay in detention for an average of 529 days before their cases are decided upon.

The top 20% of the cases register an average stay of 5 years or more.

“In my research, I’ve seen some PDLs who had stayed in detention for more than 15 years, only to be found innocent of the charges filed against them. Prolonged pre-trial detention has perverted the processes and dynamics of the criminal justice system.”

To deny or grant bail: 120 days for bail hearings alone

Moreover, the system has turned the denial or grant of bail as the most important decision point — even more important than establishing guilt or innocence, he pointed out.

“In the Philippines, the Constitution mandates that bail is a matter of right, except for those charged with capital offences — and when the evidence of guilt is strong.”

Thus, the accused charged with capital offences are automatically held in detention as “non-bailable”. Narag’s research shows that, on average, bail hearings take at least 120 days. In some cases, it can drag up to 6 years.

One result: defence lawyers shy away from invoking bail petition — as it only prolongs the case. Under the current system marked by simple calendaring inefficiencies that lead to numerous postponements, many lawyers find it "almost futile," he said.

Another reason: most of the indigent accused cannot post the amount of bail — should their bail petition be even granted. To solve this no-money-for-bail challenge, Narag helped set up the PRESO Foundation, pulling in judges and lawyers to support him, and has raised more than P1 million ($20,000), sourced via crowd-funding which he started.

Piecemeal hearings: postponement

Philippine criminal justice system is well known for piecemeal hearings during which an accused is denied bail as he undergoes the full length of trial proceedings.

The key problem is not the hearings, but the postponement of piecemeal sessions, Narag found. As hearings come once every 2 to 3 months — only to be postponed — creating a vicious cycle and unnecessary expense of taxpayers’ money. “So in one full year, PDLs can have 4 to 6 hearings scheduled, with only 1 or 2 hearings pushed through. This is especially true for drug cases,” he said.

120 days

Average period it takes for bail hearings to complete in the Philippine. In some cases, it can drag up to 6 years.Forced to make guilty plea

Thus, in order to be released on bail, after languishing in jail for 2 to 3 years, most PDLs are broken enough — and simply plead guilty to a lower offence. “They are transformed ‘from prisoners that were never convicted, to convicts that were never tried.’ This is a sorry state, indeed,” he said.

Reasons for postponement:

His continuing research among criminal justice actors show the key reasons for perennial postponement — structural, organisational and cultural.

1. Structural

Narag cited reasons for postponements based on structural reasons include: lack of equipment (say, lack of computers and internet access for online hearings), lack of jail personnel to bring PDLs to court, lack of judges, prosecutors and lawyers, and other vacancies in offices, and lack of resources in general.

2. Organisational

Organisational reasons include failure of coordination among agencies, such as police and jail officers not able to receive notice of hearings from the court; courts “over-scheduling” of hearings in a day; that is, scheduling more than 20 hearings in a day (which naturally leads to the “lack of material time” for the other accused), and many other lapses in managing the court and jail dockets. There’s also a dearth of judges, with more than 20% of judge positions left unfilled or “disorganised”.

3. Cultural

This, he said, the toughest part. In Narag’s study, culturally-driven postponements lead to purposeful delays. “Cultural reasons of postponements are the most pernicious: they are part and parcel of the litigators’ techniques to win a case, generate income, and indirectly and informally punish the accused.” It also widely known that prosecutors and defence lawyers ask for postponements to wear out the witnesses of the other party — waiting for the witnesses to move out of the country, die, or simply get disinterested.

Lawyers paid per appearance

In the Philippines, lawyers make money per “appearance" — regardless of whether a hearing is pushed through or postponed. As a result, a speedy disposition of cases is disincentivised, said Narag.

It then creates a vicious cycle. While prosecutors are usually content in prolonged trials as long as the accused is detained, defence lawyers, on the other hand, are content with prolonged trials as long as the accused is bailed out. What is important is that they regularly collect their fees.

Judge’s role

Narag stressed that, in this case, the judges' role is key. A judge must take command of the proceedings — to guard against frivolous postponements. This translates to a “court culture of efficiency" where strict schedules are adhered to, litigators’ attempt to delay is penalised, and models a behaviour of being on time and being morally incorruptible. This, he said, is the ideal set-up.

However, if judges become lenient, and allow postponements as “professional courtesy” (to lawyers who make a living), a culture of leniency emerges. “Prosecutors and defence lawyers use all the legal gobbledygook available in the rules of criminal procedures to request for postponements and delay proceedings,” he explained.

Speedy Trial Act

Narag cited the efforts by the Philippine Supreme Court to introduce the "Continuous Trial," "Justice Zones," and "Task Force Katarungan and Kalayaan.” Their initiatives need the support of trial judges, prosectors and defence lawyers, he said.

In 2017, the Philippines passed the Speedy Trial Act which calls for “continuous trials” to speed up resolution of criminal cases. As a result, trial in many drug cases are being resolved within 2 to 2-1/2 months from the time of filing, as required by the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act. Trial in other criminal cases are finished within six months, pursuant to the Speedy Trial Act.

“Our next step is to pull the latest data set, so we could know the average stay of PDLs today.” (Narag poured through nationwide data from 135,000 PDLs with the BJMP from 2013-14).

• A homicide case becomes a murder case.

• A simple theft becomes a qualified theft.

• Acts of lasciviousness becomes rape.

• A section 16 (drug use) becomes a section 5 (drug sell).

These legal strategies are often used to ensure the accused is denied bail by default. That way, the courts are mandated to decide — much later in the proceedings — whether to grant bail or not.

The culture has been that the longer a case drags, the more chances to earn, the longer the time an accused stays in detention, the more the taxpayers’ expense on food and meds for inmates, the greater the overcrowding in jails. In a pandemic, in which a deadly virus is airborne, one infection in a crowded jail could be deadly.

“The filing of the ‘nature of charges’ (homicide vs murder) and the succeeding grant or denial of bail is a weaponised tool of the different dispensers of political power in the Philippines,” he said.

Supervised release

Narag advocates for the Philippine Supreme Court to allow all the accused languishing in jails nationwide who had stayed in jail for 3 years (if accused in Regional Trial Courts, RTC), and 6 months (if accused in Metropolitan Trial Courts, MTC) to go through a "supervised release,” where the accused be monitored by a custodian — with a condition to appear in court, and to not engage in a new crime.

Many inmates are detained more than 6 months, even if their cases are lodged in MTC; and numerous people detained more than 3 years, whose cases are with the RTC.

Community Bail Bond

Dr Narag has spearheaded the Community Bail Bond programmme, under the Preso Foundation Inc., to bail out bailable PDLs. With P1 million in initial funding, the program has helped 69 people post bail so far.

The move also helped the government save Php800,000 for the inmates’ food and medicines alone (75 pesos per day per detainee). “We identify low-risk, first-time offenders (from P2,000 to P100,000 bail bond per offender).”

While in jail, foundation volunteers visit and assist inmates; talk to the Public Attorneys Office (PAO) lawyers who file a petition for bail, or motion to reduce bail. Once bailed out, volunteers provide monitoring, livelihood, and education assistance for them and family.

Upon release from detention, the participants are also referred to partner agencies for educational, emotional and livelihood services. So far, the results had been positive, he said: when there’s a hearing, the program volunteers make sure the accused attend (online). “Our appearance rate is 100%, it’s the judges who postpone.”

“These activities increase public safety and prepare the participants for reintegration into society as law-abiding citizens.”

Though the initial funding had been used up, now some of the money is coming back (bond money goes back whether an accused wins or loses). “It shows that when properly monitored and supervised, PDLs show up in court voluntarily and do not attempt to jump bail. We’re looking at ways to further expand this programme, with the help of concerned citizens.”

Useful members of society

The idea, he said, is that while awaiting trial, the accused can find employment, be responsible members of the community, and contribute to society, even when they are accused of a crime.

Today, Dr Narag teaches a dozen subjects on criminal justice and public administration in Illinois. He has sat on at least 16 Master’s and PhD Committees including students from Japan, the US and the Philippines.

He has been a member of the American Society of Criminology and sits in the Steering Committee of Asian Criminology Society. He has consulted for the Philippine Supreme Court, the Philippine Department of Justice, the Asian Development Bank and the Philippine Bureau of Corrections. He has published articles in various journals including Laws (Open-Access Journal, Punishment and Society and International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology.

Digital tools

He said innovative digital tools do help the courts and other criminal justice actors. “If they view the situation with an open heart and mind — and if they are ready to try new mechanisms outside the box — as exemplified by many court actors I have worked with, there are multiple ways to address this endemic problem,” he said.

He stressed: “We, the people, should support all our criminal justice actors who painstakingly perform their jobs despite the threats in their personal and family safety. They are putting their lives and limbs in the line of duty daily. If they succeed, we all reap the benefits of a safe society.”

Honours and awards

Narag received various awards. He was named outstanding Citizen of Quezon City in 2005, during which he also became a Fulbright scholar. He was recipient of the Dr. Martin Luther King Student Leader Award in Michigan State University in 2005, the university’s Best Student Paper award in 2010, Dangal ng Lahing Cagayano (Outstanding Cagayano Award) in 2019, and earned the “Living Hero” from the J. Amado Araneta Foundation in 2020.

“There’s huge backlog in the appointment of judges. But since you can predict when a judge retires — 20 judges retire each month in the Philippines — you can, in theory, have a system of replacement. The Judicial Bar Council of the Supreme Court (SC) submits a list of new judges to Malacanang Palace for approval, there should be improved coordination between the palace and the SC,” he said.

The Philippines has no judges-in-waiting system, where posts of retiring judges are filled immediately. Research shows it takes at least one year to fill a judge’s post in the Asian country.

Does he harbour any hatred, or bitterness?

"I had no hatred and bitterness," he said. "I was also a victim here — but a victim who will use his wretchedness to 0make positive changes in the society." Narag's life story was featured in a Philippine TV episode.