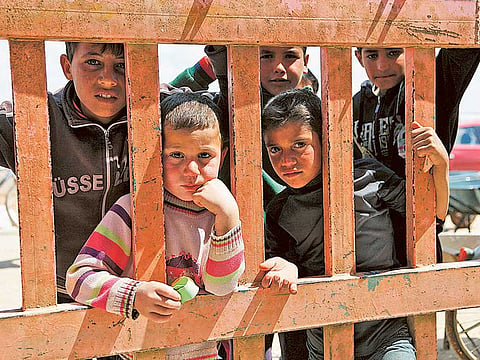

Syrian refugees caged in Jordan’s Village 5 camp

Camp-within-a-camp was part of an uneasy trade-off between Jordan and aid agencies to speed up admissions of stranded refugees

Azraq Refugee Camp, Jordan: A barbed wire-topped fence encircles a section of this bleak UN-run camp, isolating thousands of recent arrivals — whom Jordan considers a potential security risk — from other Syrian refugees.

This camp-within-a-camp, called ‘Village 5’, was set up in late March as part of an uneasy trade-off between Jordan and international aid agencies trying to speed up admissions of tens of thousands of refugees stranded in remote desert areas on the kingdom’s border.

Under the deal, Jordan agreed to let in about 300 Syrians a day, or five times more than before, on condition that newcomers are isolated in Azraq for more security checks. Jordan says strict vetting is crucial to prevent Daesh extremists, who control large areas of Syria, from infiltrating the kingdom.

In turn, aid agencies agreed to put traumatised war survivors behind barbed wire, if only temporarily.

Yet neither side expects the new admissions deal to empty out two rapidly growing encampments on the Syrian-Jordanian border. Instead, the population there — currently at 64,000, half of them children — is expected to reach 100,000 by the end of the year if fighting in Syria continues.

The two encampments sit between low earthen mounds, or berms, that run in parallel lines, about two kilometres apart in an area where the border isn’t clearly marked.

Refugees live in tents or shelters made of tarp, wood scraps and even women’s scarves, exposed to the desert’s extreme cold, heat and sand storms. Lack of latrines and trash collection has led to the spread of diarrhoea and infections.

Delivering aid to the berm has become one of the UN refugee agency’s most challenging and costly operations in the Middle East, said spokeswoman Ariane Rummery, citing “remoteness of locations, extreme weather conditions, lack of access roads, and risk of escalating insecurity.”

Other aid officials worry that ramping up support will inadvertently transform the jumble of shelters into de facto refugee camps in unsafe areas.

Yet saving lives trumps any misgivings at a time when Syrians are increasingly trapped in their homeland, said the officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorised to talk to reporters about the conditions at the berm.

Neighbouring Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan, which have absorbed the bulk of close to 5 million Syrian refugees since 2011, have severely restricted admissions, while doors to Europe are slamming shut.

Jordan has taken in about 650,000 refugees and says it has already done more than its share.

Those now waiting at the border are the responsibility of the international community, said Jordanian government spokesman Mohammad Momani. In allowing some asylum seekers to enter, “Jordan is doing its best to balance its security needs with humanitarian concerns,” he said.

Jordan argues that all those at the border are still on Syrian soil, a claim disputed by the international group Human Rights Watch. The border is believed to run between the two berms and most tents are pitched closer to the southern, Jordanian-controlled berm, said researcher Adam Coogle.

The head of the Norwegian Refugee Council in Jordan, Petr Kostohryz, said Jordan is “perhaps the only country in the region retaining at least partially open borders.”

At the same time, refugees live “in the middle of the desert, with zero access to services, with high degrees of crime and exploitation,” he said.

Refugee Khalid Mallak, 34, his wife and six children were among those who made the dangerous trip from Syria to the Azraq camp in Jordan’s eastern desert.

The Mallaks left the Syrian capital of Damascus in mid-January and reached Hadalat three days later. “The area was full of insects and even rats,” Mallak said of the border camp.

After three months, the family was admitted to Jordan and was moved to Azraq, the only permitted destination for refugees. In fenced-in Village 5, they received food and basic supplies, but often waited for hours to collect them, said Mallak.

The family was allowed to leave the restricted area after a month, and now lives in a part of Azraq where they have greater freedom of movement.

A Jordanian security officer prevented Associated Press reporters from approaching Village 5.

Azraq consists of rows of white prefab shacks that can house up to 51,000 Syrians in four sections, or villages. Only two villages were populated after the camp’s opening in 2014.

However, a third section, Village 5, filled up over the past six weeks, as Jordan admitted more than 16,000 refugees under the new policy, said Kostohryz, the NRC chief.

Last week, the first group of 1,500 refugees was allowed to move out of the restricted area, in what the NRC hopes will be the start of integrating all newcomers into the camp.

Meanwhile, aid agencies are facing growing challenges at the berm, a 2.5-hour drive from the nearest Jordanian town, including an 80-kilometre stretch over unpaved desert.

Aid workers cannot enter the camps for security reasons, and set up distribution points near the southern berm. Jordanian troops stand atop the earth mounds and screen refugees.

Refugees permitted to climb over the berm fetch water or line up, often for hours, to register with the UN or receive canned food, dry rations and fruit.

Crowds have repeatedly surged toward aid workers amid rumours that distribution was ending for the day, an aid official said. Troops have responded with tear gas or warning shots.

During Ramadan, which begins next week, refugees will be lining up in scorching temperatures while fasting during daylight hours.

A lawless atmosphere prevails in the camps, said aid officials, citing accounts by refugees. War profiteers with no intention of seeking asylum steal rations from the most vulnerable, the officials said.

Some refugees at the berm don’t seek asylum, for fear of being rejected by Jordan and sent into a more dangerous area of Syria.

Momani confirmed that some have been rejected on security grounds, but did not provide figures. He argued that this does not amount to expulsions — problematic under international law — because Jordan never admitted them as asylum seekers.

It’s not clear how long the faster pace of admissions will last. Jordan promised the United States earlier this year to let in at least 20,000, aid officials said. White House officials declined comment.

Existing shelters in Azraq can now house several thousand more refugees” the camp is designed for an additional 75,000 people.

However, Jordan is unlikely to let in large numbers of refugees. It says it has confidential evidence that IS sympathisers posing as refugees are trying to infiltrate the kingdom, which is a member of the US-led military coalition against the extremists in Syria and Iraq.

Even if most of those waiting at the berm were moved to Azraq, many more would likely take their place, Momani said.

“If we let all of these people into that camp [Azraq], what’s going to happen a week after that?” he said. “You will get 120,000 stranded people on the border.”

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox