No solution in sight as Nile dam standoff deepens

Ethiopia’s power generation sparks Egyptian-Sudanese ire

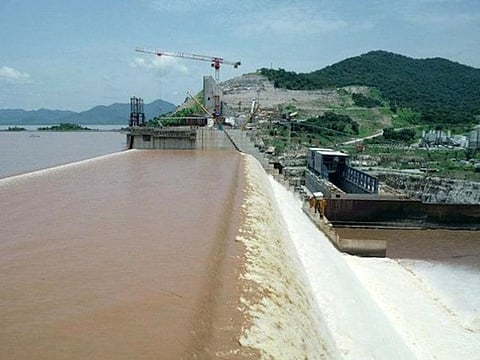

Ethiopia’s start of generating power from a contested dam built on the Blue Nile has fueled worries in downstream countries Egypt and Sudan and diminished prospects for a negotiated solution to the long-running dispute.

Over the past 10 years, the three riparian countries have held on-and-off talks to resolve the row over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), but without achieving a breakthrough.

Unilateralism reigns supreme

On Sunday, Ethiopia announced the onset of electricity production from the mega-dam, a step that both Egypt and Sudan decried as unilateral.

“Egypt confirms this unilateral step is considered an insistence from the Ethiopian side on breaching its obligations under the 2015 agreement on declaration of principles,” the Egyptian Foreign Ministry said, referring to a framework pact signed by the three countries in the Sudanese capital nearly seven years ago.

Ethiopia has already unilaterally carried out two fillings of the multi-billion-dollar dam, raising worries in Egypt and Sudan over shortages in their water shares. Ethiopia reportedly plans a third filling later this year.

Sudan has called Ethiopia’s partial electricity generation a “substantial violation” of Addis Ababa’s international legal obligations.

“Sudan stresses its rejection of all one-sided measures related to the filling and operation of the dam,” the Sudanese government said.

“The latest measure starting the operation of the electricity-generating turbines contradicts spirit of cooperation and constitutes a substantial violation of Ethiopia’s international legal obligations,” it added.

Egypt and neighbouring Sudan have been pushing for a binding legal accord before the filling and operating of the Ethiopian hydropower dam.

Egypt relies heavily on the Nile to cover the water needs of its population of over 100 million people. As many as 97 per cent of Egyptians are living along the banks of the Nile where the country’s most fertile farmland is.

Blaming Ethiopia for the current stalemate after nearly a decade of talks, Egypt has demanded that any new negotiations be conducted within a specific timeframe. Negotiations, brokered by the US and the African Union on the dispute, have led to nowhere. No fresh talks are expected any time soon while Cairo accuses Addis Ababa of seeking to impose a status quo solution.

Development with strings attached

“Egypt agrees on the use of the dam for generating electricity, but without harming Egyptian and Sudanese interests,” ex-Egyptian irrigation minister Mohammed Nasr Eddin said this week. ”The Ethiopian government does not want to reach a fair solution to the dam crisis,” he told Egyptian private TV station Saada Al Balad.

In 2011, Ethiopia started building the GEDR apparently taking advantage of the unrest in Egypt, which followed mass protests that forced long-time president Hosni Mubarak to step down.

Ethiopia said the dam on the Blue Nile near the border with Sudan is necessary to meet electricity needs of its population. When completed, the dam will be Africa’s largest hydropower plant, generating around 6,000 megawatts of electricity, with potential for exports.

Ethiopia has also denied Egyptians’ worries and defended its construction of the $5 billion dam as being vital for its development and lifting its population of around 103 million out of poverty.

After he took office in mid-2014, Egyptian President Abdul Fattah Al Sissi sought to improve ties with Ethiopia and opted for negotiation to resolve the dam dispute.

The Egyptian leader has repeatedly acknowledged Ethiopia’s right to development, but without harming his country’s Nile share. On March 23, 2015, Al Sissi, Sudan’s then president Hassan Al Bashir and the then Ethiopian prime minister Hailemariam Desalegn signed in Khartoum the agreement on Declaration of Principles, to help solve the GEDR crisis.

Existential issue for Egypt

As negotiations hit a dead end, Al Sissi warned that resolving the dam dispute is crucial for regional stability and called for international pressure on Ethiopia.

He has contended that the Nile waters are a “matter of life” for Egyptians, cautioning that harming Egypt’s share is a “red cross” that must not be crossed.

A drop in the Nile flow to Egypt will take a toll on its access to freshwater, farming output and power generation by the High Aswan Dam, according to experts. With its mushrooming population, Egypt is seen heading towards absolute water scarcity, even without GEDR fallout.

Egypt argues that the Ethiopian dam compromises its historical rights to the Nile. Under a 1959 treaty, Egypt gets 55.5 billion cubic metres of the Nile waters each year. According to a 1929 treaty, Egypt has the right to veto any project by the Nile upstream countries that would affect its share of waters.

Ethiopia and other Nile upstream countries have dismissed both accords as colonial-era legacy and urged the riparian countries to ratify a comprehensive framework agreement to replace the 1959 treaty that gives Egypt and Sudan the lion’s share of the Nile waters.