Crackdown brings apparent lull in Karachi violence

Operation by police and paramilitary government Rangers seems to be having some positive effect

Karachi: Rampant violence has terrorised Karachi, Pakistan’s biggest city and economic heartbeat, in recent years, but a recent security crackdown seems to have brought a lull in the bloodshed.

Kidnappings for ransom, sectarian attacks and gang warfare have spiralled since 2008, terrifying the city’s 18 million inhabitants and prompting tens of thousands of businessmen to flee to the safety of Punjab province.

The city claimed a grisly record last year as 2,124 people were murdered on its streets, according to the Citizens-Police Liaison Committee (CPLC), the highest number since records began nearly 20 years ago.

“The merciless killings have turned this ‘bride of cities’ into a city of ghosts and darkness,” said Tauseef Ahmad Khan, a political analyst, referring to Karachi’s Persian nickname.

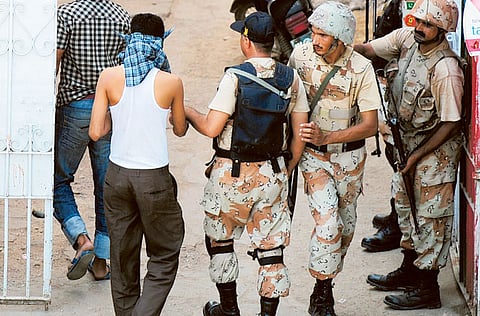

But an operation by police and paramilitary government Rangers in the city’s tangled maze of teeming streets, launched early September on the orders of the central government, seems to be having some positive effect.

The CPLC said that in September 155 killings were reported — down from 280 in August. With a total of 2,058 murders up to the end of September 2013 it is on course to beat last year’s record, but the crackdown appears to have at least slowed the killings.

Aftab Chunar, the head of the autopsy department of the city’s largest state-run Civil Hospital, said that before the operation he was receiving 16 to 18 bodies a day. Now the figure has fallen to three or four.

On the streets, there is relief.

“After a long time there is a feel of normalcy in the city. Now it seems that criminals are on the run and I pray that the good old times return to the city,” said Aziz Rana, a 45-year-old bank worker.

Under the military rule of general Pervez Musharraf, the murder rate hit a low of just 76 killings in 2003 before rising to 777 in 2008, when he was ousted.

The figure shot up from 2010 onwards as criminal gangs backed by rival political parties grew in power and sectarian and ethnic violence swelled.

Amir Ahmad Shaikh, until recently the police chief of southern Karachi, the worst affected part of the city, said gangsters backed by political clout had held Karachi to ransom.

Extorion became a hugely lucrative source of earnings for the gangs, with one intelligence official said around $14 million a month was extorted in Karachi.

Traders and businessmen are the ideal prey for the extortionists, and many have fled the city, which accounts for more than 40 per cent of Pakistan’s GDP.

“Some 40,000 to 45,000 traders and shopkeepers have migrated from Karachi to the Punjab province as their properties and lives both are not safe and secured here,” said Atiq Mir, chairman of Karachi Traders Alliance, a representative body of the city’s small to medium traders.

The crackdown has seen Rangers use powerful motorbikes to chase suspects down the narrow, twisting streets which remained off-limits in previous missions using heavy vehicles.

Hundreds of alleged target killers, extortionists and gangsters have been arrested since the start of the operation, Rangers and police say.

Fateh Mohammad Burfat, professor of sociology and criminology at the state-run Karachi University, said the crackdown seemed to be working.

“Peace seems to have returned to the city and the common man, after a long time, has breathed a sigh of relief ever since the operation began,” he said.

“It is the neutrality of the operation which is key to its success and so far the police and rangers are executing the operation indiscriminately and with objectivity.”

Others are not convinced the lull will last. Making arrests is one thing, but getting convictions in Pakistan’s sclerotic legal system is another.

Police say more needs to be done to protect witnesses, currently too scared of reprisals to give evidence.

Tauseef Ahmad Khan, a professor at Federal Urdu University in Karachi and a prominent newspaper columnist, said the real proof of the operation’s effectiveness would come with the Islamic holy month of Muharram, due to start in early November.

“It seems artificial to me though there are some vital signs as they have arrested criminals even-handed,” professor Tauseef Ahmad Khan said.

“But one would like to see how the month of Muharram passes and it would be a good litmus test of the ongoing operation.”

Muharram, which culminates with Ashura, the holiest day in the Shiite Muslim calendar when the faithful march to mourn the seventh-century killing of Imam Hussain, is frequently a flashpoint for sectarian violence.