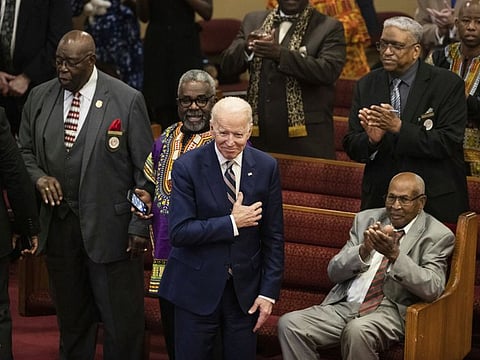

Can Biden sustain double-digit lead?

Trump’s poor handling of pandemic may have broken political stalemate

Washington: Joe Biden’s commanding advantage in the race for the White House shows no sign of abating. He led by 15 percentage points in an ABC News/Washington Post survey of registered voters on Sunday, and he has held a nearly double-digit lead in an average of polls for more than a month.

The last time a candidate sustained such a large advantage for so long was nearly 25 years ago, when Bill Clinton led Bob Dole in 1996.

After a quarter-century of closely fought US elections, it is easy to assume that wide leads are unsustainable in today’s deeply polarised country. Only Barack Obama in 2008 managed to win the national vote by more than 3.9 percentage points. The other big leads all proved short-lived.

But as Biden’s margin endures well into its second month, it becomes harder to assume that it is just another fleeting shift in the polls. Perhaps the lead is not just different in size and length but also in kind. It’s possible the nation’s political stalemate has been broken, at least for now, by one issue: President Donald Trump’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic.

With over three months to go, there’s still more than enough time for the race to change in the president’s favour. The race has already shifted quite a bit over the last three. The possibility that the president could enjoy a turnout advantage or a relative advantage in the battleground states may mean that it wouldn’t take much to bring about a more competitive race. But the race might not inevitably revert to competitiveness, as it has so many times since 1996, without deeper changes in the underlying dynamics of the contest.

Obama and Clinton campaigns

After all, Obama’s victory in 2008 was the exception for a reason. It was underpinned by a huge change in the fundamentals of the race: The economic collapse resulting from the financial crisis. In other recent races, polling shifts were usually the products of events, whether it was a successful convention, a cringeworthy gaffe or a wave of unflattering news coverage. Once the news environment returned to normal, so did the polls.

Hillary Clinton, for instance, briefly held fairly sizeable leads, peaking at around 7 percentage points in early August and mid-October 2016. In each case, she at once benefited from favourable, event-driven news coverage — the Democratic convention and her perceived victories in the presidential debates — and a wave of unfavourable, event-driven coverage for Trump, who feuded with the family of a Gold Star soldier in late July and faced the “Access Hollywood” revelations in early October. The news environment did not remain so favourable to Clinton for long. Neither did the polls. She wasn’t able to sustain more than a 6-point lead for a full month of polling.

It remains possible that Trump’s current slump is just a larger and more protracted version of the news-driven shift that we’ve seen many times in recent years. Biden’s lead has lasted long enough to cast some doubt on that interpretation but not necessarily so long to preclude it.

Negative coverage

The president has undoubtedly faced a steady stream of negative coverage over issues like the Bible photo op at Lafayette Park, his reluctance to wear a mask during the pandemic, his administration’s spat with Dr Anthony Fauci. For the purpose of understanding the president’s standing in the polls, perhaps there is some similarity between the Trump administration’s feud with Fauci and Trump’s attacks on Khizr Khan or former Miss Universe pageant contestant Alicia Machado four years ago.

At the same time, Biden has avoided the limelight. If Biden becomes the focal point of the race and the string of bad news for Trump comes to an end, perhaps the polls might revert to where they were in April or May.

The other possibility is that Biden’s lead is more like Obama’s in 2008. If so, it is not the result of the vagaries of the news cycle. Instead, Biden’s lead might follow from a fundamental change in the underlying dynamics of American politics, much as the financial crisis reshaped the race in 2008. This time, it wouldn’t be the economy, but the coronavirus.

Pandemic fight could decide contest

In this sense, the fight against coronavirus has the potential to define American politics the way an armed conflict might: It poses a threat to the health and safety of the public, and voters support the effort to defeat it even at a significant economic cost.

Unlike a recession — but again somewhat like a crisis or war — the emergence of the coronavirus was not necessarily bad news for Trump. It offered an opportunity for non-partisan, presidential leadership on a pressing issue that transcends traditional political divisions.

Not even a high death toll was necessarily a problem for the president’s political fortunes. Gov. Andrew Cuomo seems to have emerged with stronger ratings in New York despite tens of thousands of deaths, just as Franklin D. Roosevelt and George W. Bush emerged stronger after the catastrophic Pearl Harbor and 9/11 attacks. Winston Churchill presided over his troops’ defeat in France in 1940 and still claimed his place as a prominent figure in world history in the very same month.

For the same reasons, crisis, war and the coronavirus offer as much downside as upside for elected officials. They eclipse the usual political fights, and if voters lose confidence in their leaders during crisis, it can be the end of their careers, whether it be Lyndon B. Johnson or Neville Chamberlain.

Politics of coronavirus

The coronavirus is not war. Many Americans, including the White House, dispute the pandemic’s severity. But the politics of coronavirus nonetheless seem simple: It has become the dominant issue in American life, and voters have reached an overwhelmingly negative view of how the president has handled it. Not surprisingly, Trump’s standing has suffered. His approval rating has fallen to around 40% among registered voters. His position against Biden has deteriorated at a similar pace.

As Harry Enten of CNN has pointed out, poll after poll shows a tight relationship between presidential vote choice, approval of the president’s handling of the coronavirus, and judgements on which candidate would do a better job on the issue. The relationship between attitudes about the coronavirus and the presidential race is clearer than for any issue in recent memory.

Trump’s only hope

If the coronavirus is the problem for Trump, then his challenge is straightforward: His numbers could suffer so long as coronavirus remains the dominant issue and so long as voters believe he has handled it poorly. A change in media coverage might not only be insufficient, but also less likely, since the recent wave of bad news is a reflection of the underlying state of the country. Instead, the president’s prospects for a comeback seem to hinge on a more favourable judgement from voters on his handling of coronavirus or on the virus becoming a less important issue to voters.

Whether it’s realistic to expect the public to revisit its attitude about the president’s handling of coronavirus at this stage is an open question. Whether the coronavirus eventually becomes less salient to voters is probably a question for epidemiologists as much as any political analyst.