A kneed to know

Ancient legs found in Nefertari’s raided tomb are probably the last surviving remains of the egyptian Queen, says a new study

CAIRO

In 1904, the pioneering Italian archaeologist Ernesto Schiaparelli cracked open a tomb in Egypt’s Valley of the Queens. The crypt, which had been lost for millennia, showed signs of long-ago disaster. Two things were clear to the archaeologist: This tomb was once the final resting place of Queen Nefertari. And, plunderers looted the burial site in antiquity, possibly within a few hundred years of its royal inhabitant’s death.

The 3,200-year-old room was ransacked to its walls. The chamber, once covered in murals memorialising the queen’s beauty, was two-thirds bare. The pillagers left behind broken furniture, and reduced her rose granite sarcophagus to pieces.

Not everything, however, was destroyed.

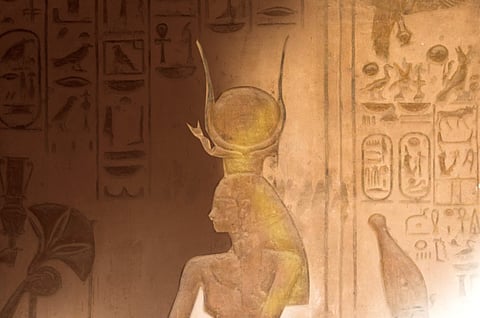

The surviving wall paintings, of the queen and a menagerie of animal-headed gods, have been described as the ancient Egyptian equivalent of the Sistine Chapel. Schiaparelli recovered an enamel disk bearing the name of King Ay, a few dozen figurines and some cracked vases. He found a pair of sandals. And in the funeral chamber sat a pair of mummified legs, little more than knees connected to fragments of femur and tibia.

Since the time of Schiaparelli’s discovery, most archeologists assumed that the legs were the last surviving remains of Nefertari. The queen lived in the 13th century BC. Though her husband, Pharoah Ramses II, had many wives and children — he fathered about 100 descendants — Nefertari was his favourite consort. (As evidence, archeologists point to her lavish tomb as well as a temple Ramses II dedicated in her honour.)

Probability

But it would take more than a hundred years, an international team of scientists say, for the assumption about Nefertari’s legs to become scientific probability. They are quite likely the queen’s knees, according to the group of archaeologists and chemists who recently published an analysis in the journal PLOS One.

Simply because the legs were found in the tomb was not conclusive, argued study author Joann Fletcher, an Egyptologist at the University of York, Britain.

“We had no way of knowing if these were Nefertari’s remains or not,” Fletcher said to NPR. “They could have been washed into the tomb at a later date during one of these occasional flash floods that do occur in that part of Egypt.”

The scientists performed a detailed X-ray exam of the legs. The images indicate the remains came from the same body, and likely belonged to a person who died between the age of 40 and 60. Due to the thinness of the bones, the scientists posit these were “high status” knees, not those of a labourer who lived outdoors.

Comparing the knees to modern and ancient bone samples, the researchers estimated the person was about five-feet, four-inches tall. This is taller than most ancient Egyptian women and the same height as the average ancient Greek or Egyptian men. (Nefertari was, by the wall mural’s accounting, statuesque.)

The elaborate sandals, the study authors wrote with a “certain reservation,” would have fit a woman about five-and-a-half feet tall.

DNA tests on 1-centimetre-square slices of skin and muscle were inconclusive. But a chemical analysis of the embalming agents uncovered animal fat and little else, consistent with mummification practices during the time of Ramses II.

And radiocarbon dating ruled out an older burial, or the idea that remains wound up in the queenly tomb much later in history.

All told, the study authors say the clues stacked up in Nefertari’s favour. “Thus, the most likely scenario is that the mummified knees truly belong to Queen Nefertari,” they wrote. “Although this identification is highly likely, no absolute certainty exists.”

(To that point, a University of Liverpool archaeologist told the Guardian that a lack of DNA results did not push the conversation beyond the starting assumption: that the bones, found in the queen’s tomb, were her legs.)

Stripped back

At the same time, the fractured bones and missing remains came with a grim corollary. The scientists believe robbers quickly stripped the dead queen of her raiments, dismembering her mummy as though it was some sort of pharaonic piata. The shredded legs were left behind after everything else of value was taken.

“You do get that feeling that there’s a real degree of ripping apart human remains to get to the wealth,” Fletcher said to NPR.

As advanced CT scans and other analytical techniques become cheaper and more widely available, scientists are able to non-invasively tease out secrets locked within ancient sarcophagi. In what was long thought a jar of organs, Cambridge archaeologists discovered a tiny Egyptian mummy in May. The embalmed foetus, as young as 16 weeks, is the smallest yet found.

A few months later, Dutch museum curators were shocked to see the bodies of 47 mummified infant crocodiles lining the walls of a sarcophagus. The curators were expecting to find just two adolescent reptiles.

—Washington Post