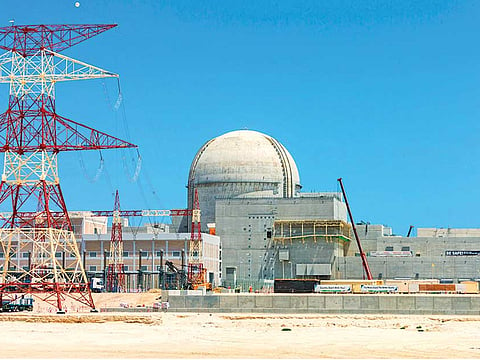

The core of UAE’s nuclear aspirations

The Barakah plant is entering its final stretch of build out

As infrastructure projects go, the Barakah nuclear plant in the UAE is big and certainly makes a bold statement in a region that sits on nearly two-thirds of the world’s proven oil reserves.

In total, the plant will have four nuclear reactors, built with 1.4 million cubic yards of concrete, 250,000 tonnes of reinforced rebar and at its peak employed 22,000 construction workers.

The UAE chose to embark on this project with the South Korean energy group Korea Electric Power Corporation or KEPCO, the first time the Asian country exported its nuclear technology.

The 42-year-old Mohammad Al Hammadi is marking his tenth year as CEO of Emirates Nuclear Energy Company, with the first reactor scheduled to come online in 2018.

The US-educated electrical engineer, like the leadership in the UAE who championed this idea, firmly believes there’s a strategic importance in diversifying the country’s energy mix to reduce its reliance on oil.

Diversification

“The UAE growth and demand for electricity is three times the global average and that growth is the development of the nation,” he said in front of a state-of-the-art simulator centre, “That growth is being met by renewable energy, by gas, by nuclear and that will diversify the energy policy for the country.”

There are a few items worth exploring from the chief executive’s statement. Due to its skyrocketing energy demand and over reliance on hydrocarbons, the UAE is eager to come off the list as a Top 10 emitter of CO2 emissions on a per capita basis according to the World Bank.

At the same time, it will eventually reduce the current reliance on natural gas imported from Qatar, where relations remain strained due to the economic embargo in place.

When the country embarked on this $20 billion investment back in 2008, a key component was to bring nuclear power to the fore to save the UAE’s over 97 billion barrels of proven reserves for export, about 6 per cent of the global total. The belief was, why burn $100 a barrel crude to meet domestic energy needs?

Hammadi said that strategy remains in place despite the more than 50 per cent drop in prices with a facility that has a lifespan of six decades. “We will have different energy prices, different economic situations and conditions, but these investments are done for the long term,” he said.

After the Fukushima Daiichi disaster in 2011, many claimed this marked the beginning of the end for nuclear energy.

ENEC officials, most notably Hammadi, stress that Japan’s facility represented the first generation of nuclear technology and it was the tsunami that toppled the plant; something that they underscore is not a risk at their facility which sits on the calmer waters of the Gulf about 280 kilometres from the capital.

But there is much more at stake here beyond supplying a quarter of the country’s energy needs and reducing hydrocarbon emissions by 21 million tons a year.

When completed, the UAE will be the first Arab state with a nuclear power programme in a region rife with unrest and plenty of ongoing questions from the Trump administration about Iran’s long term plans about its nuclear development.

Abu Dhabi signed the so-called “123 Agreement” with the US back in 2009 which has strict safeguards on nuclear enrichment and led to further international support thereafter including a greenlight for development by the Vienna based IAEA.

“The UAE’s programme has often been referred to as the gold standard,” said Robin Mills, CEO of Qamar Energy. “They have been very concerned to stress that this is not about proliferation and weapons but that it is a very clean programme.”

Hammadi went further to stress “it is illegal to enrich or reprocess any uranium here in the country” under the law passed by the President of the UAE and enforced by the domestic regulator. No one, however, can dispute that the decision to proceed with such a project has triggered a race to roll-out plans for nuclear power in the region.

Saudi Arabia for example, as part of its 2030 diversification plan, wants to construct 16 nuclear power reactors over the next quarter century. Oil importers Jordan and Egypt also have nuclear ambitions to follow suit over time but don’t have the cash reserves of the Gulf oil exporters.

It is a concept that the world is still trying to get its head around. A region that sits on an abundance of oil and has year-round sunshine for solar power is on a nuclear energy development path when others like Germany are saying “nein”.

The writer is CNNMoney’s Emerging Markets Editor.