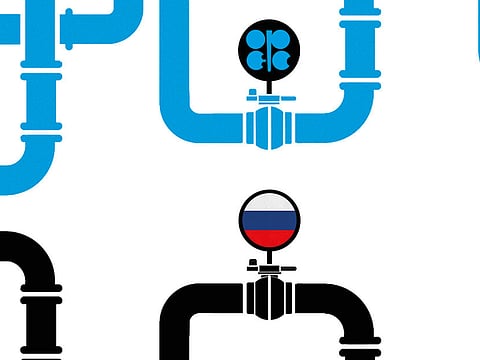

Opec should keep building its bridges with Russia

They are certainly not getting much by way of help from the US

A global recession, both $140 (Dh514) and $30 oil, the US shale revolution, a market share war, and output cuts. Opec’s 60-year history has rarely confronted a more challenging period than the past decade.

Now, instead of enjoying the higher prices resulting from 18 months of joint production cuts with a coalition of other major producers, the alliance faces new problems. A tweet-happy American president is ramping up geopolitical risk, renewed sanctions are hammering Iran’s exports, Venezuelan production is tanking as its economy collapses, and a political attack from Washington in the form of the “NOPEC” bill.

The alliance of exporters met on Sunday (September 23) in Algeria to consider its response to these challenges. The Opec response to crises over the past decade offers clues to the path it might take forward.

Ten years ago, a banking crisis triggered a global economic downturn and a crash in oil prices as demand was obliterated. After peaking at a record $147.50 a barrel in July 2008, Brent crude fell as low as $36.20 by year-end. Facing catastrophe, Opec members put aside internal squabbles and agreed production cuts that were historic in their speed and scale — output fell 16 per cent in just eight months.

It worked, and prices began to recover in 2009 even as the world was mired in recession. After Chinese consumption came roaring back in 2010, the group was able to open its taps again as the cost of crude surged back toward $100.

From 2011 onward, Opec enjoyed years of riches and relative stability as oil traded near $100 a barrel, but a threat was emerging. A new generation of wildcatters from North Dakota to Texas was deploying innovative fracking technology to tap previously inaccessible shale oil deposits. Opec was blind to the danger at first, then downplayed the risk even as some members raised the alarm — reasoning that shale was an expensive business and the alliance simply had to bide its time.

By mid-2014, US production had jumped more than 50 per cent, crude prices were teetering on the brink and it was clear this new industry was reshaping the global market as Opec stood by and watched.

By late 2014, there was a global oil glut, prices were collapsing and US shale was showing no signs of slowing. Pressure increased on Opec to respond as it had done in 2008 and cut output, but Saudi Arabia had a different plan.

Energy minister Ali Al Naimi rejected requests from fellow members and opened the taps in a war for market share. At first it seemed to work — the price slump worsened and put immense financial pressure on Opec, but also triggered a collapse in US drilling and forced producers to close the taps.

By mid-2016, the gambit looked shaky. Crude still languished near $40 a barrel, putting some Opec members on the brink. However, US production was rising again after drillers made huge cost cuts and bloated crude stockpiles threatened to depress prices for years to come.

A new Saudi minister, Khalid Al Falih, was appointed and set about engineering a historic agreement including major producers from outside the group. By late 2016, he had secured the cooperation of 10 other nations, most importantly Russia, who agreed to remove 1.8 million barrels a day of supply from the market.

Thanks to this deal, crude has staged a spectacular recovery from its bruising slump. In April, Opec and its allies concluded they had achieved their goal of rebalancing the market and even higher prices beckoned.

If only it was that simple. Opec’s moment of celebration faded fast as US President Donald Trump threw a spanner in the oil market. Accusations on Twitter that the body was artificially inflating prices were followed by his renewal of sanctions on Iran’s exports and additional penalties that worsened the decline of Venezuela.

Within a month, Saudi Arabia and Russia were signalling their intention to roll back the cuts, and in June they successfully pressured the rest of the group to agree. After 18 months of fairly harmonious supply restraint, some Opec members were hastily reopening the taps, while others were hesitant.

Where does Opec turn now?

Lessons from the group’s history point eastward, toward a permanent partnership with Russia, said Harry Tchilinguirian, head of commodity strategy at BNP Paribas SA. It’s the most effective counterbalance to the shale revolution, which continues to reshape the market, he said.

“US shale oil will be reaching the Atlantic Basin, and Asian markets alike, more regularly and in greater volumes as pipeline connections to the Gulf Coast and oil terminals are built or expanded,” Tchilinguirian said. “This competitive challenge, along with demand dynamics that accompany the transition to cleaner energy, give Opec an incentive to establish a permanent relationship with Russia and a growing number of non-members,” he said.

Whether such an alliance would actually prove effective at managing the market in the long term is another matter, said Bob McNally, president of Rapidan Energy Group.

“The jury remains out as to whether this new Saudi-Russia led entity will succeed longer term at preventing future booms and busts or, like a number of other temporary ad hoc institutions since oil’s earliest days, it will succumb to indiscipline,” McNally said.

— Bloomberg