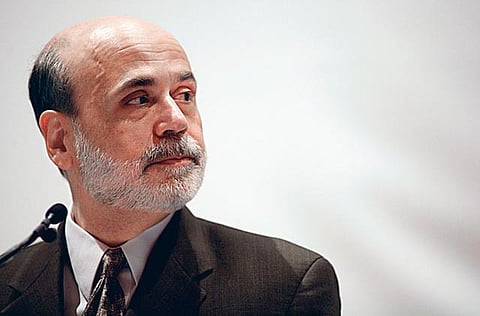

Bernanke argues from a realty bubble

Bernanke said the linkages between monetary policy and home prices were weak

You can almost hear the collective sigh of relief emanating from the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, and the nearby offices of Alan Greenspan, to Fed chief Ben Bernanke's elegant, econometric argument that low interest rates didn't cause the housing bubble.

The Fed, in other words, is guilty of one count of regulatory oversight failure. As to the charge of using interest-rate policy to inflate the housing bubble that burst and destabilised the entire financial system, the defendant is not guilty.

In a speech to the American Economic Association's annual meeting in Atlanta last weekend, Bernanke said the linkages between monetary policy and home prices were weak. His conclusions, based on econometric models and statistical analysis, may resonate with his AEA audience. For the rest of us, they leave something to be desired.

For example, Bernanke takes great pains to rebut criticism that the funds rate was well below where the Taylor Rule, developed by Stanford economist John Taylor, suggested it should be following the 2001 recession. The Taylor Rule uses actual inflation versus target inflation and actual gross domestic product versus potential GDP to determine the appropriate level of the funds rate.

Substitute forecast inflation for actual inflation, and the personal consumption expenditures price index for the consumer price index, and — voila! — monetary policy looks far less accommodating, Bernanke said.

It's always easier to start with a desired conclusion and retrofit a model or equation to prove it.

Monetary policy

More than half of the countries with tighter monetary policy than the US witnessed greater house price appreciation. For Bernanke, this proves "the relationship between the stance of monetary policy and house price appreciation across countries is quite weak".

What if easy money is a necessary but not sufficient condition to explain the magnitude of housing bubbles across countries?

Unlike his predecessor, who argued that low short-term interest rates could not have caused the bubble because housing is a long-lived asset, Bernanke acknowledged the effect on adjustable-rate mortgages. ARMs as a share of total mortgage volume rose from about 15 per cent in mid-2003 to more than 35 per cent in 2004 and early 2005.

It wasn't the prevailing rates on the ARMs that exacerbated the bubble, Bernanke argued. It was the exotic nature of instruments such as pick-a-pay and negative amortisation ARMs, along with lax underwriting standards. These were regulatory, not interest rate, failures.

I know Bernanke has given this issue a great deal of thought and devoted the Fed's resources to finding the correct answer. Still, the defence sounds divorced from reality.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox