Cancer's new nemesis: mRNA-based jab zaps tumours, enters human trials

mRNA-based vaccine designed to fight a wide array of solid tumours go for Phase 1 trial

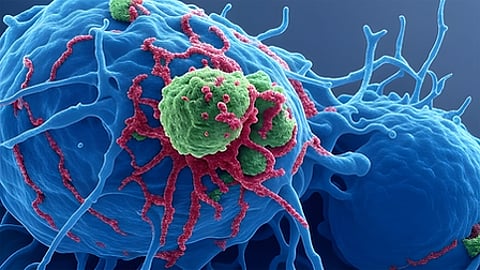

In a groundbreaking development that could revolutionise cancer treatment, researchers have advanced an mRNA-based vaccine designed to combat a wide array of solid tumours without the need for personalisation.

This “off-the-shelf” approach aims to trigger a broad immune response against multiple cancer types.

One study recently published in Nature, led by Adam J. Grippin of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, shows that existing SARS‑CoV‑2 mRNA vaccines (like COVID shots) can make some cancers more responsive to immune‑checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) drugs, even though the vaccines are not cancer‑specific.

In a Phase 1 trial, researchers closely monitor participants for adverse reactions and determine the best way to administer the treatment (e.g., pill, injection) before moving to larger trials.

Immune‑checkpoint drugs

Immune‑checkpoint drugs (such as anti‑PD‑1/PD‑L1) work best when a patient already has some anti‑tumour immune activity; “cold” tumours with weak immunity often do not respond.

Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors unleash the immune system's T cells to attack cancer by blocking proteins that tumours use to hide from immune detection.

In a nutshell: these drugs target "checkpoints" such as PD-1 on T cells and PD-L1 on tumour cells, which normally act as "brakes" or "checkpoint" to prevent overactive immunity.

Cancer exploits this by ramping up PD-L1 to signal T cells to stand down, allowing tumours to grow unchecked. Blocking the interaction removes the brake, reviving T cell aggression against the tumour.

Personalised mRNA cancer vaccines can heat up these tumours but are slow and complex to make.

Researchers found that in mouse models (in a lab), SARS‑CoV‑2 mRNA vaccination triggered strong type I interferon signals, activating innate immune cells, which then primed “CD8+ T cells” to attack tumour antigens, especially when combined with ICIs as tumours upregulated PD‑L1.

Better survival

Similar immune activation patterns and increased tumour PD‑L1 were seen in humans after vaccination.

Among patients who received an mRNA COVID vaccine, within about 100 days of starting ICIs, had better median and three‑year survival, including those with immunologically cold tumours, researchers found, citing "retrospective" clinical data.

mRNA vaccines gained global recognition during the coronavirus pandemic for their ability to instruct cells to produce proteins that stimulate an immune response.

Now, this technology is being “repurposed” for oncology.

Unlike traditional cancer vaccines, which often require tailoring to an individual's specific tumour mutations — a process that is time-consuming and expensive — the new vaccine targets common mechanisms across various cancers.

Pre-clinical studies have shown promising results.

In mouse models (in lab trials) of melanoma, brain cancer, and bone cancer, the vaccine boosted the production of “type-I interferons”, key immune signals that help identify and eliminate tumour cells.

When combined with immune-checkpoint inhibitors — drugs that remove brakes on the immune system — the vaccine demonstrated enhanced efficacy, shrinking tumours and preventing regrowth.

These findings suggest the vaccine could complement existing therapies, potentially improving outcomes for patients with hard-to-treat cancers.

Current human trials

The UK-led trial of mRNA-4359 is testing the vaccine in patients with advanced solid tumours, including melanoma and lung cancer.

This phase 1 study focuses on safety and initial efficacy, enrolling participants to evaluate how well the vaccine primes the immune system without causing undue side effects.

Milestone

While results are pending, the transition to human trials represents a milestone, as most experimental cancer vaccines fail to progress beyond animal testing.

This isn't an isolated effort.

Researchers at the University of Florida have reported a surprising discovery that could pave the way for a similar universal vaccine.

Their mRNA approach sensitised tumors to immunotherapy in mouse models, enhancing the immune system’s ability to attack cancers broadly rather than targeting specific markers.

Advances

In another advance, a blood-cleansing method using light-inactivated tumour cells is entering its first clinical trial as a cancer vaccine, aiming to harness whole-tumour antigens for a comprehensive immune response.

At Johns Hopkins, a novel liver cancer vaccine has achieved responses in a rare pediatric disease, with 25% of patients showing deep responses and potentially becoming cancer-free.

Meanwhile, the 2025 ESMO Congress highlighted immune-modulatory and mRNA-based vaccines that could boost the benefits of immune checkpoint inhibitors across solid tumors.

These vaccines, including those from Moderna and other biotechs, are showing improved responses in patients who recently received mRNA COVID vaccines, suggesting cross-priming of the immune system.

Cancer vaccine research: The big picture

The field is bustling with innovation. A nanoparticle-based vaccine from the University of Massachusetts Amherst prevented tumour growth in mice across melanoma, pancreatic, and triple-negative breast cancer, achieving rejection rates up to 88% in some models by fostering long-term immune memory.

Similarly, UCLA's off-the-shelf vaccine ELI-002 2P elicited strong immune responses in patients with KRAS-mutated cancers, safely training the body to fight tumour-driving mutations.

Personalised mRNA shots

Personalised mRNA vaccines are also progressing, with potential to revolutionise treatment if regulatory hurdles are cleared.

However, the push toward universal options addresses scalability issues, making treatments more accessible.

As noted in a comprehensive review, mRNA therapies are on the cusp of approvals by 2026-2027, with key trials shaping the future.

Biotech firms are leading the charge, from antigen-targeting to AI-assisted discovery of universal targets.

Geopolitics

mRNA cancer shots have become a hot-button geopolitical race.

Russia has also announced plans for a free global cancer vaccine, though experts emphasise the need for large-scale trials and verification.

Skepticism remains, as some claims outpace evidence, but the accelerating pace of breakthroughs in 2025 — spanning AI, biotech, and materials science — signals rapid progress.

Challenges

Despite the excitement, challenges persist.

Cancer's ability to mutate and evade the immune system means no single vaccine may eradicate all forms.

Trials must demonstrate long-term efficacy and safety across diverse populations.

Regulatory bodies like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will scrutinise data, especially amid debates over mRNA technology's broader support.

If successful, a universal cancer vaccine could shift oncology from reactive treatments like chemotherapy to proactive immune training, reducing side effects and costs.

Pivotal moment?

It might prevent metastases and relapses, offering hope to millions. As one researcher put it, "Cancer has a Gator problem," referring to UF's aggressive pursuit of these therapies.

While still early, the entry of mRNA-4359 and similar vaccines into human trials represents a pivotal moment.

Combined with ongoing research, it fuels optimism that a universal cancer vaccine could soon become reality, transforming how we combat one of humanity’s deadliest diseases.