Ravi Shankar was the master of sitar

Revered in the East, hailed in the west

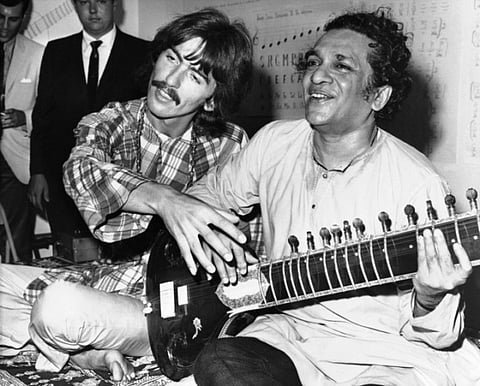

Dubai: George Harrison called him the godfather of world music, Yehudi Menuhin compared him to Mozart and John Coltrane named his son after him.

He was at ease whether performing for half a million people in New York’s landmark Woodstock of 1969 with Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix, or an intimate concert for less than a hundred people in India with the legendary table maestro Allah Rakha by his side, or teaching the intricacies of the sitar to Harrison.

For Pandit Ravi Shankar considered music as the essence of being, and bridging the gap between the musical languages of east and west was for him the ultimate celebration of life.

The Indian sitar legend died on Tuesday at the age of 92 in California. He was suffering from respiratory problems and wore an oxygen mask for his last public performance at the California State University last month.

“His health has been fragile for the past several years and on Thursday he underwent a surgery that could have potentially given him a new lease of life,” daughter Anoushka Shankar and wife Sukanya said in a statement sent to Gulf News. “Unfortunately, despite the best efforts of the surgeons and doctors taking care of him, his body was not able to withstand the strain of the surgery. We were at his side when he passed away,” they said, calling him “husband, father and musical soul”.

Millions of fans across the world yesterday paid tributes to the man who popularised the sitar — a seven stringed instrument musically linked to the lute — and Indian music beyond the borders of east and brought them to the global stage.

“Although it is a time for sorrow and sadness, it is also a time for all of us to give thanks and to be grateful that we were able to have him as a part of our lives. His spirit and his legacy will live on forever in our hearts and in his music,” Anoushka and Sukanya said in the statement.

“On and off stage, uncle was essentially two different personalities,” Shankar’s niece and Uday Shankar’s daughter Mamata Shankar told Gulf News yesterday. “When he was playing the sitar, it felt like he was engaged in a deep conversation with God. Off stage, he was just like a child — full of life, indulging in fun and gossip, filled with curiosity about the latest gossips and jokes,” said Mamata, herself an acclaimed dancer, choreographer and actress. “My father was 20 years older than Ravi Shankar, and he used to love him like a son rather than a younger brother. Today, it feels like we have lost our father again,” she said.

Born to a musical family in the Indian city of Varanasi on the banks of the Ganges, Shankar soaked in the traditions and nuances of Western music and life when he began touring Europe and America in the 1930s with the dance troupe of brother Uday Shankar. It was during these tours that he discovered Western classical music, jazz and cinema.

In 1939, music maestro Ustad Allauddin Khan took Shankar under his tutelage. Spending more than seven years in rigorous and isolated training, Shankar mastered the sitar and the surbahar — another plucked string instrument often described as the bass sitar. He often studied and practised with Khan’s children Ali Akbar Khan — who would become one of the most accomplished musicians of his generation but shun the limelight and awards — and Annapurna Devi, who would become Shankar’s first wife.

The musical career that Shankar began with his first public performance in 1939 would only end a month before his death. But it was his association with the Beatles, particularly Harrison, his participation at the Woodstock and the Bangladesh relief concert of 1971, and his collaboration with musicians of all genres — ranging from Menuhin to André Previn — that brought international fame and attention to Shankar and his craft.

Harrison’s fascination for India and Shankar’s subsequent emergence as the darling of the hippie movement of the 1960s is the stuff of legends, and left its footprints in Beatles tracks such as ‘Within you, Without you’. Dozens of musicians would travel to India to record with Shankar or discuss ideas for collaboration: he was the face of Indian musical tradition and its many possibilities to the world. The venue of his performances would vary from the US to the USSR to Japan and Europe.

But eventually disillusioned by the drug-obsessed and stunt-savvy world of pop music, Shankar began concentrating more on classical music from mid 1970s. This is the period that would consolidate his legacy — in music concerts, film scores, including the music for Lord Attenborough’s award winning ‘Gandhi’, and in bold experimentations which would win him three Grammys.

Paradoxically, he would stay most of his years in the West rather than in India, where some classical purists scoffed at his interpretation of the ragas and found his performances stylized to suit the Western ear. He set up a music school in Los Angeles, as well as one in Mumbai.

His personal life was never easy.

He separated from Annapurna Devi a few years after marriage, and following a formal divorce in 1982, he married Sukanya in 1989 and they had two daughters. In between, he lived with dancer Kamala Shastri in the late 1940s, while an affair with New York-based concert producer Sue Jones led in 1979 to the birth of Norah Jones. Her 2003 Grammy awards brought an unexpected burst of publicity for Shankar, who reunited with his first daughter after many years.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox