Through the lens of identity

Pema Tseden is first Tibetan director to graduate from Beijing Film Academy

Beijing: Pema Tseden, the Tibetan filmmaker and writer, felt ashamed.

For years, he had written stories and screenplays switching between Chinese and his native Tibetan with a nimble linguistic ambidexterity. But lately, grueling filming and publicity schedules had worn him down, leaving him with the time to write only in Chinese, his second and sometimes preferred working language.

The feeling that he was neglecting his native tongue peaked recently when he found himself at an event to introduce a Tibetan edition of his book Tharlo, which had been translated from the original Chinese.

“Someone else had to translate my own novel into my native language,” the soft-spoken director of critically acclaimed films like “Jinpa” and “Tharlo” said in a recent interview. “It felt a bit absurd.”

It seemed almost like a confession of guilt, coming from someone whose Tibetan identity has been central to his work and life. And it underscored the contradictions that crop up regularly for a new generation of Chinese-trained Tibetan filmmakers.

Tseden, 49, is thought to be the first Tibetan filmmaker working in China to shoot a film entirely in the Tibetan language and the first Tibetan director to graduate from the prestigious Beijing Film Academy.

He is an example of an increasingly rare type in China: an art-house director who has managed to work within the censorship-heavy system while still producing films and stories that resonate with audiences far beyond the system’s confines.

He has done so by avoiding overt references to politics in his films despite pressure from some Tibetans abroad to speak out about what they say are increasingly repressive conditions at home. Though all of his movies are set in Tibet or Tibetan areas - among the most sensitive topics in China - they do not mention the Dalai Lama, whom the Chinese government accuses of supporting Tibetan independence, and they rarely depict characters from the Han Chinese ethnic majority.

But most Tibetans agree: Tseden’s films are rare in that they offer a Tibetan’s view of Tibet, painting an unvarnished, sometimes angry, portrait of a windswept plateau on the fringes of a fast-encroaching modernity.

“Pema Tseden’s films are authentic in the sense that they capture the social issues that bind every Tibetan,” said Tsering Shakya, a professor of Tibetan literature and society at the University of British Columbia.

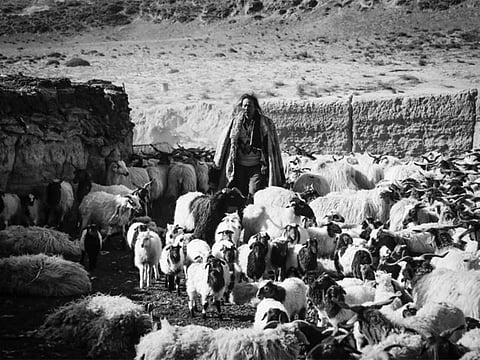

Shakya pointed to Tseden’s film Tharlo about a shepherd who makes a rare trip out of his isolated mountain home to a police station in town where he is told that he must register for a government-issued identity card.

“I know who I am, isn’t that enough?” says the unassuming shepherd, played by Shide Nyima.

What may seem like a harmless observation takes on a deeper meaning against a highly politicised background. The Red Army seized Tibet in 1951, and China has ruled it ever since. Tensions have grown in the region since a 2008 rebellion by Tibetans, which prompted a government-led security clampdown and a number of self-immolations by Tibetans in protest.

Cerebral and bespectacled, with thick eyebrows and a calm demeanour, Tseden took a sip of tea in a small rented high-rise apartment in a gated complex not far from Beijing’s glamorous shopping and entertainment district. In addition to making films, he is also a prolific writer and translator. The first English-language anthology of his short stories, Enticement: Stories of Tibet, was published last fall.

Many of Tseden’s stories draw on his experience growing up the son of nomadic herders in Qinghai, high on the Tibetan plateau. Back then in his remote mountainous village, he recalled, books were so rare that a dictionary could be traded for a yak. He credits his grandfather, a monk who had him spend hours after school copying Buddhist scriptures by hand, with instilling in him an appreciation for Tibetan language and culture.

“I think I was a literati in a past life,” Tseden said with a smile.

The first in his family to finish college, Tseden worked for nearly a decade as a schoolteacher and civil servant in Qinghai before moving to Beijing for film school. He brought with him a desire to break the stereotype of Tibetans encapsulated in “Serfs,” the classic 1963 Chinese film about the exploitation of a Tibetan serf and his emancipation by the People’s Liberation Army.

“Whenever I introduced myself as a Tibetan in middle school and high school, the first word everyone would blurt out was: ‘serf,’” Tseden said. “For many people, their understanding of Tibet is still stuck on that level.”

Through his films, Tseden sought to portray a Tibet stripped of sentimentality and stereotypes. In The Silent Holy Stones (2005), his first feature film, crimson-robed monks binge-watch television shows - a far cry from the heavenly, mist-shrouded Himalayan paradise of popular Western imagination and the far-flung region of former serfs of popular Chinese imagination.

In September, he won the award for best screenplay in the Orizzonti section of the Venice Film Festival for his latest film, “Jinpa,” about a Tibetan truck driver who accidentally runs over a sheep and picks up a hitchhiker who is on a mission to kill his father’s murderer. The driver, already worried about bad karma from killing the sheep, wonders if he should stop the murder.

Today, Tseden is often credited with bringing up an entire film industry on the Tibetan plateau, a region where movies were once so irrelevant that they were synonymous with television shows. His films are now made almost entirely with Tibetan actors and crew members, something that was impossible 20 years ago, he said. He also mentors younger Tibetan filmmakers in China who are striking out on their own, like Sonthar Gyal and Lhapal Gyal.

Because Tseden’s films touch on issues related to ethnic minorities, they are vetted through a stricter-than-usual censorship process. Every line in the script is scrutinised.

Despite the intense scrutiny, all six of Tseden’s feature films have received the official “dragon seal” of approval from Chinese censors - a testament, critics say, to the subtlety of his cinematic expression. (His films have had limited box office success in China, though, in part because of their slow pacing and art-house aesthetic.)

In conversation as in his films, Tseden is cautious. When asked about what some critics say are China’s increasingly assimilationist policies toward ethnic minorities, he said that he felt “very helpless.” He added, “When you are a relatively small subject and you encounter something with greater power, of course you have no choice but to change and adapt.”

But his films can be direct. A sense of despair pervades the 2011 film Old Dog, in which a shepherd would rather kill his beloved nomad Tibetan mastiff than see it stolen or sold to meet the growing black market demand among Chinese businessmen. “A grim and uncompromising allegory of the waning of Tibetan traditions and values,” critic Jeanette Catsoulis wrote in a New York Times review.

The Tibetan language also features prominently throughout Tseden’s films. His insistence on shooting in Tibetan, particularly his native Amdo dialect, comes as bilingual education for ethnic minorities in China.

Though the boundaries of what is acceptable are constantly shifting, for now, Tseden said, “It’s possible to still express yourself without touching on the so-called sensitive stuff.”

Several years ago, Tseden moved from Beijing to Xining, the capital of Qinghai, not far from the secluded mountain village where he grew up. Moving back at a time when more Chinese artists are thinking about moving abroad was a natural decision, he said.

“Being an artist in the system in China is a difficult life,” he acknowledged. “But freedom is a relative concept. And this is the land I belong to.”

The New York Times News Service