Same differences

Scientists see twins as the perfect laboratory to examine the impact of nature versus nurture

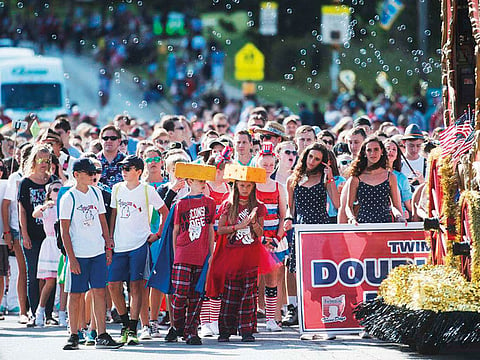

Every August, for the past 43 years, Twinsburg, Ohio, has hosted the biggest gathering of twins in the world. Two decades ago, organisers added an attraction to the lineup of parade, talent show and hot-dog dinner that drew more than 2,000 pairs this year: The chance to participate in research. Scientists vie for tent spots to test such things as twins’ exposure to the sun, their stroke risk and their taste preferences.

“Every year we get more (research) requests than we can handle,” says Sandy Miller, a Twins Day Festival organiser and mother of 54-year-old twins. “We just don’t have room for all the scientists who want to come.”

The research tents are a big hit, says Miller. “The area is always crowded, and every year, people call in advance to see which programmes will be featured,” she says. “The twins do it because they want to. They know the outcomes help everyone — not just twins, but you and me as well.”

Since English scientist Francis Galton published a paper on the heritability of traits in 1875, researchers have been fascinated by how the behaviour and health of identical twins differ throughout their lifetimes.

The intense interest in how genes affect our lives has inspired scientists around the world — including in the United States, the Netherlands, Denmark, China and Cuba — to create large national registries of twins. The largest of these, which has data on 85,000 pairs of Swedes, is being used to research allergies, cancer, dementia, cardiovascular disease and other topics.

Sandy Miller of the Twins Days Festival says the research tents are a big hit. “The area is always crowded, and every year, people call in advance to see which programs will be featured,” she says. “The twins do it because they want to. They know the outcomes help everyone - not just twins, but you and me as well.”

What are twins?

“Twins are nature’s experiment,” says Australian neuropsychiatrist Perminder Sachdev, who runs the Older Australian Twins Study, which was started ten years ago and has recruited more that 300 pairs of twins older than 65 to analyse how physical activity, psychological trauma, alcohol use and nutrition affect their brains, psyches, metabolisms and hearts.

Because identical twins are the result of a single egg that splits into two, they share the same DNA and provide a perfect laboratory to answer age-old questions about the roles of genes and environment: Why does one twin get breast cancer and not the other? How does obesity increase one’s risk of Type 2 diabetes? Do genetics really determine whether you are more likely to own a gun or go to college?

“When you do a study in the general population, you’re comparing people of different ages, sex, backgrounds, dietary histories, educational and socioeconomic levels,” Sachdev says. “But with twins, you automatically control for many of these variables.”

Identical twins are 99.999% the same: Till one ends up in a space flight, other does not

Genetic-sequencing tools that plumb our biology in more detail than ever are providing new answers to why we get sick or act and look the way we do. In this era of molecular genetics, scientists can pinpoint which genes are linked to diseases — and more recently, whether certain genes are turned on and off over time, a field known as epigenetics.

“We can tease out more of the genetic components of nature versus nurture,” says Christopher Mason, a geneticist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. When identical twins are born, they’re 99.999 percent the same, but as they age, the effects of lifestyle, trauma, stress or disease cause their genes to be expressed in distinct ways. “They experience the slings and arrows of the environment differently,” he says. “Twin studies help you see the drivers of change.”

Identical twins Scott Kelly, US astronaut, and his twin Mark (right), at ‘Global Roadshow’ in New York.

In one of the purest twins experiments ever designed, Mason was part of the team that compared the effects of a year spent in space on 52-year-old US astronaut Scott Kelly with the Earth-based experience of his identical twin, Mark. Researchers discovered that Scott Kelly’s time on the International Space Station had altered the expression of 7 per cent of his genes, including those involved in blood oxygenation and DNA repair. “It was surprising how many genes responded to the stress of spaceflight,” Mason says.

Mason says the research offers insight into how to study the effects of harsh environments. “We want to leverage the capacity of twin studies to understand human physiology at extremes, such as scuba diving, climbing Mount Everest or flying fighter jets,” he says.

What happens to twins separated at birth?

Studies of reared-apart twins have shown that in general, half the differences in personality and religiosity are genetically determined, but for a trait like IQ, about 75 per cent of the variation, on average, is genetic, with only 25 percent influenced by the environment.

Sudies of heart disease in twins have shown that genes confer a potential, but the environment often determines whether that potential is expressed.

Studies of heart disease in twins have shown that genes confer a potential, but the environment often determines whether that potential is expressed. For example, perfect pitch tends to run in families and may even be tied to a single gene, but without early musical training, the trait is unlikely to be expressed.

In the documentary Three Identical Strangers, the triplets separated at birth revealed differences in their susceptibility to mental illness, with the one who was reared by an authoritarian father more seriously affected than the two with warmer, more nurturing parents.

Decades-long studies of identical and fraternal twins — and in some cases, triplets — who had been separated at an early age and reared in what were often strikingly different environments have documented the important interaction of nature and nurture and help to explain the relative contributions of each to how a child develops.

Nancy Segal, a psychologist at California State University, Fullerton, and herself a fraternal twin who has made a career of twin studies, starting with the Minnesota Twin Family Study, is the author of Born Together — Reared Apart: The Landmark Minnesota Twins Study, published in 2012. She has also written Twin Misconceptions: False Beliefs, Fables and Facts About Twins. She said the studies highlight the importance of keeping twins, especially identical twins, together when adopted.

As was depicted in this year’s US documentary Three Identical Strangers, about identical male triplets separated at birth and their growing up, Segal said, “The triplets deeply resented having been separated. They lost out on wonderful years they could have had together. There was an immediate bond, an understanding of one another, that was obvious as soon as they found each other.”

49% nature and 51% nurture

Twins studies have been so popular that one 2015 meta-analysis found that researchers had looked at no fewer than 17,800 traits — including depression, cardiovascular disease and gun ownership — involving more than 14.5 million twin pairs over the past 50 years. It concluded that both “nature” (what you’re born with) and “nurture” (what you’ve been exposed to as you age) are nearly equally important for understanding people’s personalities and health: The variation for traits and diseases was, on average, 49 per cent attributable to genes and 51 per cent to environment.

But Segal has another view.

“A strict dichotomy between genes and environment is no longer relevant; they work in concert,” she said. “It’s trait-specific,” with different ratios depending on the characteristic in question. “In an individual person, the contributions of genes and the environment are inestimable,” Segal said, “but on a population basis we can estimate how much person-to-person variation is explained by genetic and environmental differences.”

There can also be changes in the genome of an identical twin when the egg divides, resulting in a defect in a particular gene, Segal said.

Twins studies or general population studies: Where should the dollars go?

Despite a consensus on the value of twins studies, there’s disagreement over where research dollars should be focused. Some scientists believe genetically sequencing large numbers of unrelated people — in what are called genome-wide association studies, or GWAs — will result in the next wave of scientific progress.

“Instead of doing another study looking at the heritability of schizophrenia with twins, let’s do a very large GWA study with 250,000 people and identify where it exists in the genome,” says University of North Carolina psychiatrist Patrick Sullivan, who founded a consortium of 800 researchers studying mental-health disorders. “We can get directly into the biology. That’s something twin studies can’t do.”

But John Hopper, an epidemiologist and director of Twins Research Australia begs to differ. He terms the practice of sequencing people by the thousands as a “sledgehammer” approach.

Twins add important context about their life experiences that might be missed in these larger studies, he says. For example, to assist an international study based at the University of Southern California, he is recruiting pairs in which one twin has breast cancer and the other doesn’t.

“We’ll be able to fill in the gaps by asking, ‘Who went through puberty first?’ “ says Hopper. “The magic of studying twins is that you get insights into the causes of disease that you couldn’t get any other way. There’s gold among twins.”

— Washington Post

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox