The one thing the director Ron Howard wanted to get right about Star Wars was the Kessel Run. In the original 1977 film, Harrison Ford’s Han Solo boasted of having navigated this apparently deadly hyperspace route in “less than 12 parsecs”. But in the Solo spin-off, audiences would get to see the escapade first-hand — and discover it hadn’t been quite the breeze Han’s vague, offhand bluster had implied.

“The idea that you’d heard him casually bragging about this thing, and then would discover what a near miss it had been, and all the obstacles he’d had to outwit — I loved that,” says Howard. “I just liked the idea that everything was far more complicated than he would ever dare let on afterwards.”

Funny, that. Howard isn’t an obvious kindred spirit to Star Wars’ foremost smuggler and scoundrel: the 64-year-old former Happy Days star is Hollywood’s level-headed all-rounder-in-residence, with a directing CV that encompasses Splash, Backdraft, Dan Brown, Frost/Nixon and the Oscar-laden A Beautiful Mind. But Solo: A Star Wars Story has been his own personal 12-parsec Kessel Run — a breakneck rip through some of the most treacherous blockbuster-making conditions around.

This time last year, Solo was in crisis. Its original directors, the Jump Street and Lego Movie duo Phil Lord and Christopher Miller, were taking their signature improvisational approach to the material. But on a production with this many moving parts, it had slowed down the shoot to a crawl, while the all-important Star Wars tone was getting lost in the zany high jinks.

For five months, everyone pressed on in hope, but things reached an impasse in June 2017, so Lucasfilm president Kathleen Kennedy met Howard for breakfast in Los Angeles, to put some feelers out. “Basically halfway through the meal she said, ‘I think we’re going to have to make a change, and we’re building our list of candidates to quickly go to, so would you like to be on it?’,” Howard recalls.

His instinct was to say no: he had never taken on a half-finished film before, and “the whole idea made me feel a little uncomfortable,” he admits. But he agreed to read the script, and as he did, the prospect of taking on Solo started to feel like “an interesting test of my mettle”, especially as he hadn’t made a large-scale fantasy adventure since Willow in 1988. Two days after Lord and Miller were officially removed from the project, Howard told Kennedy he’d do it. Four days after that, he was standing on set.

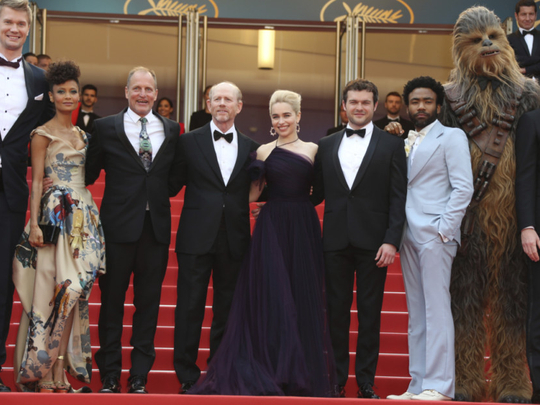

I meet Howard the day after Solo screened at the Cannes Film Festival, on the Carlton Hotel’s seventh floor terrace. It’s a bright afternoon, and John Williams’ Star Wars theme drifts up from an advertising installation on the Boulevard de la Croisette. Alden Ehrenreich, aka Han 2.0 — and a former leading man for the Coen brothers, Francis Ford Coppola and Warren Beatty — is on the terrace too, contemplatively chewing on a grapefruit, while actor-comedian-rapper Donald Glover, who plays Han’s unscrupulous sometime-ally Lando Calrissian, is indoors reclining on a sofa. “Don’t get too relaxed!” a publicist advises Glover, only half-jokingly. Everyone laughs. Solo’s making-of story is a hard one to tell — at least for the time being, while the wounds are still fresh. But all three are here to tell it.

Not that theirs has been the only disturbance in the Star Wars franchise since Disney’s multi-billion takeover of Lucasfilm in October 2012. Rogue One, the first of the stand-alone Star Wars Story films, underwent considerable last-minute reshoots, during which the film’s co-writer Tony Gilroy informally took the reins from director Gareth Edwards. And two more directors, Colin Trevorrow and Josh Trank, have both been removed from their respective franchise entries — the forthcoming Episode IX and a mystery side-project — at the pre-production stage.

But the Solo farrago was by far the most dramatic: partly because it became public at such a late stage in production, partly because it entailed the downfall of a directing partnership about whom no one — certainly not Howard, Ehrenreich or Glover — has a bad word to say.

“With Phil and Chris, as opposed to honing a scene, we would try out a lot of different versions of it,” says Ehrenreich. “But we still improvised with Ron, still found the scenes together.”

“We did a lot of character work with Phil and Chris that was really good, which may not necessarily have happened with other directors,” offers Glover. “They took a risk and Ron was able to build on it.”

“I know this sounds strange, but Kathleen is a director’s producer,” Howard says. “And so sometimes she’s got herself into precarious situations by trying so hard to make a fit work.” (Howard and Kennedy have known each other for decades, while his friendship with her old boss, George Lucas, stretches back to 1973 film American Graffiti.)

At first, Kennedy tried to bring the production under control by giving a more active supervisory role to Solo’s co-writer Lawrence Kasdan — a Star Wars veteran who collaborated on the scripts for The Empire Strikes Back, Return of the Jedi and The Force Awakens, and an accomplished director in his own right. But when that arrangement broke down — with theoretically less than a month left on the shooting schedule — the nuclear button was pressed.

“It’s the most literal application of the term ‘creative differences’ I’ve ever seen,” Howard says. “And no movie should have to go through that. And with two guys with as much integrity and talent as Chris and Phil, it’s unfortunate indeed.” There was no formal transfer of power, but Howard says Lord and Miller “reached out and said if I wanted to meet them they’d be willing to, which I thought was incredibly collegial and gracious.”

He also sought advice from Lucas — “who just told me to trust my instincts,” he recalls with a quizzical look. “It was a little Yoda-like.” (Lucas would later drop by the set at Pinewood Studios, just as Howard had visited him on the sets of the original trilogy and the prequels.)

But his first priority was soothing the cast and crew, not least his 28-year-old lead. “I knew Alden was going to do great, and he was of course upset, concerned and a little bit thrown by the whole transition,” Howard says. “But I found him really easy to collaborate with, and we just continued to go with what he was doing.”

Bringing back an already-iconic character like Han was onerous enough as it was. Ehrenreich had a pep talk over lunch with Ford before the shoot began, and also studied his performance in the earlier Star Wars films, “just to understand the way the character worked.” But he didn’t aim for impersonation: “Francis Ford Coppola said this thing about Robert De Niro in Godfather Part II: he didn’t think that Robert De Niro could play a young Brando, but he did think he could play a young Vito Corleone,” Ehrenreich tells me. “It’s a little bit the same here. This is not a Harrison Ford biopic.”

When he arrived back on set, he was expecting “some kind of course-correction. But Ron was supportive of what I’d already been doing, and encouraged me to keep going with it.”

Around 70 per cent of the finished film of Solo comes from Howard’s end, although playing “who shot what?” is much harder than you might think. (In fact, given all of the above, the end product is amazingly seamless.) A suite of comic scenes featuring Paul Bettany as the space gangster Dryden Vos struck me as obvious Lord and Miller, but in fact they were shot by Howard: Bettany’s character was originally a lion-like creature played in performance capture by The Wire star Michael K Williams, but he was unavailable for the required four extra months of shooting, so his part was recast.

In order to keep pace on his television work, Glover flew the writers of his TV series Atlanta to London, “and we were all working when I was done on set and on the weekends,” he says. Glover also senses the upheaval improved his and Ehrenreich’s on-screen chemistry, giving Han and Lando an extra jab of frontier comradeship. “Going through something traumatic always forces a sort of camaraderie,” he says. “Not to say the thing with the directors was traumatic!” he adds hastily. “But once it happened, it brought us even closer.”

Once filming was back under way, Howard found himself drawing on his own eclectic previous experience: the scrappy car chases of his 1977 debut Grand Theft Auto, the making-of-an-icon dimension of his work on the young Albert Einstein series Genius, the lightning-speed man-machine synergy of his Formula 1 biopic Rush.

For Ehrenreich, watching Howard switch from set-piece mode to close-up character work in a heartbeat gave him a new perspective on what Star Wars actually is, beyond the series’ mythological underpinnings and what he calls the “beat-up space meets Morocco” aesthetic of the props and sets.

“What I realised through working with Ron is that Star Wars constantly oscillates between all of these different dynamics — comedy, drama, action, pathos,” he says.

As for Howard, it just felt like second nature. “I did start to feel an uncanny connection to it, this innate understanding of the rhythms and shifts in tone,” he says. Perhaps Lucas’s Yoda-like guidance wasn’t quite so abstruse after all.

———————

Don’t miss it!

Solo: A Star Wars Story is out now