Iraq protests are meaningless when the government is on autopilot

Protesters filling the streets is no substitute for picking a prime minister and cabinet

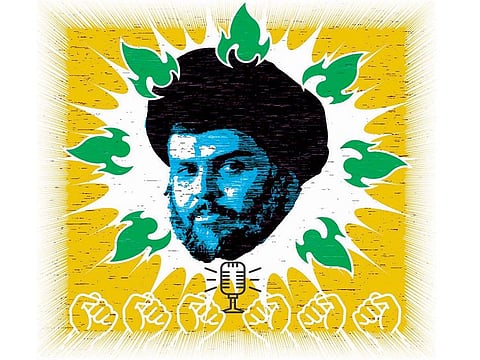

How many people responded to Moqtada Al Sadr’s call for demonstrations against the US military presence in Iraq? Did they, or did they not, come out in the “millions” he wanted? What is certain is that the crowds in Baghdad were substantial, and highly disciplined — in contrast to the mobs gathered by Iranian-backed militias to attack the US embassy on New Year’s Eve.

No one doubts the ability of Al Sadr, a radical Shiite cleric-politician, to rouse a rabble with anti-American rhetoric; in the aftermath of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, his word was sufficient for thousands of incensed — and ill-equipped — young men to hurl themselves against US forces, with predictable consequences. More recently, his formidable voting block of supporters has made him the country’s second-most powerful politician, only slightly behind Tehran’s main man in Baghdad, Hadi Al Amiri.

But Al Sadr has yet to demonstrate the capacity to deploy his political clout in any meaningful service of his supporters — to address their economic grievances.

On the contrary, he has contributed to their plight: His political party is complicit in the corruption, incompetence and sectarianism of successive coalition governments in Baghdad. Ministries run by Al Sadr’s nominees — like health and transportation — were especially notorious in the early, defining years of Iraqi democracy.

Two weeks have passed since the Iraqi parliament’s non-binding resolution calling for American troops to be expelled, but any negotiations toward that outcome will require a new prime minister in place.Bobby Ghosh

This failure makes his recent reinvention as an anti-graft crusader as credible as his highly questionable credentials as a religious scholar. Until recently, he benefited from the lack of any other political outlet for disaffected Iraqis, especially among the majority Shiites; if anything, his rivals were even more discredited among that cohort. But the protests that have wracked Iraqi cities since last fall indicate a growing plague-on-all-your-houses sensibility. That many protesters appear to be young Shiites is especially worrying for Al Sadr. They should be his constituency, but instead have grown disenchanted with his promises of change.

His demonstration of clout last week will not have reassured them. For one thing, the anti-American focus of his message is too narrow: Those in the streets have been protesting against all foreign meddlers, including Iran. Al Sadr, on the other hand, is ambivalent about the Islamic Republic, paying obeisance to Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei even as he occasionally aims rhetorical jibes against Khamenei’s regime and its proxies in Iraq.

Demands for political reforms

For another, Al Sadr’s rallies did not address the protesters’ main demands for political reforms, clean government and better services. He has merely talked a good game about supporting these aspirations. Never mind better government, Iraq has very little government at all. Weeks after the resignation of Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi, Iraq is essentially running on autopilot — mainly because Al Sadr and Al Amiri can’t agree on who should get the job.

Among other things left in limbo has been the question of the US military presence. Two weeks have passed since the Iraqi parliament’s non-binding resolution calling for American troops to be expelled, but any negotiations toward that outcome will require a new prime minister in place. If Al Sadr can’t make that happen, his rallies will have had no meaningful consequence beyond stealing the limelight from the protests.

And not for long. The protesters may have ceded centre stage today, but they are determined to reclaim the public square in the weeks ahead. If that happens, any discussion of how many people Al Sadr brought into the street will be strictly academic.

— Bloomberg

Bobby Ghosh is a columnist and member of the Bloomberg Opinion editorial board. He writes on foreign affairs, with a special focus on the Middle East and the wider Islamic world.