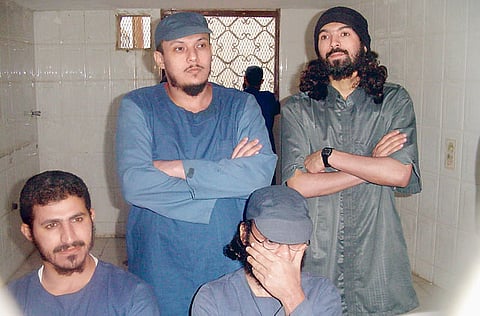

An army of jihadists ready to do battle

Dubbed an ‘urgent priority' by the US, Yemen has become a regional hub for Al Qaida

The market at Ja'ar, a small city in Abyan province in southern Yemen, is on a filthy, dusty road strewn with garbage, plastic bottles, cans and rotten food. Plastic bags fly on the hot wind and feral dogs sniff around the vegetable stalls. Minibuses and donkey carts jostle for space on the crowded street.

A thin short man with a well-groomed beard and shoulder-length hair stands on the road. He is dressed in the Afghan style: shalwar kameez, camouflage vest and an old Kalashnikov. In the past two years Al Qaida has established a local franchise in Yemen, Al Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), which has claimed responsibility for audacious attacks including the attempt to assassinate the British ambassador to the capital, Sana'a, earlier this year.

Guidance from militant leaders

In Yemen, recruits can study ideology and take guidance from militant leaders, including the Yemeni-American cleric, Anwar Al Awlaki, who has been described as "terrorist number one" by the Democrat chairman of the House homeland security sub-committee, Jane Harman. Al Awlaki is believed to have given guidance to the so-called underwear bombing suspect, Omar Farouk Abdul Mutallab, and to Major Nidal Hassan, accused of murdering colleagues in shootings at Fort Hood.

With its conservatism, ragged mountains, unruly tribes and problems of illiteracy, unemployment and extreme poverty, Yemen has been dubbed the new Afghanistan by security experts.

The Guardian spent two months in the country, travelling to the tribal regions of Abyan and Shabwa, where Al Qaida has set up shop and where suspected US drone attacks have killed scores of civilians and few insurgents. Speaking to jihadists, security officials and tribesmen, it became clear how a combination of government alliances, bribes, broken promises and bungled crackdowns has allowed Islamists to flourish and led to the emergence of the country as a regional hub for Al Qaida.

Miserable situation

Ahmad Al Daghasha, a Yemeni writer who specialises in Islamic and jihadist issues, says two factors are responsible for the growing influence of Al Qaida. "First there is the local situation, which is miserable, politically and economically," he says. "Then there is the foreign oppression that we all see on television whether in Iraq, Afghanistan or Palestine that gives Al Qaida's rhetoric legitimacy."

In the south, government control is slipping away fast. Bandits, lawless tribes, secessionists and jihadists are all fighting the government. Though they have few ideological connections, the groups are all contributing to one thing: a failing state where extremism can flourish.

The rise of Al Qaida in Ja'ar has been a gradual process of radicalisation as generations of volunteer fighters have returned from conflicts abroad: the Afghan war against the Soviets in the 1980s, as well as the Nato-led war against the Taliban and the war in Iraq in 2003. Veterans of these conflicts, as well as jihadists who have never fought abroad, are in the streets of Ja'ar fighting for influence. In the 1970s and 1980s, Ja'ar had been predominantly a socialist town. But when the government in Sana'a fought the socialists in a short civil war in 1994, the Islamists fought alongside them. When the socialists were defeated, the Islamists were encouraged to take control of the area. Quranic centres, the Yemeni equivalent of madrassas, were established with government support.

Over the next 10 years, the town became a base for the Islamists: they had jobs and they received their salaries from the government and money that came in support of the Quranic centres.

I spoke to Faisal, a thin skeleton with a thick moustache balanced awkwardly on his small head on the floor of his Spartna living room. A former Socialist party member and head of the Young Artist Association in Abyan, he watched the Islamisation of Ja'ar happen.

"The socialists were defeated on July 7, 1994," he said. "On July 8 a group of Islamists came and picked me up, blindfolded me and took me to the headquarters of political security. I was handcuffed and beaten there. They wanted to know if I was a communist and their commander declared I was one. Then they tied my arms to a tree and hung me there and started beating me up with a stick.

Cinema closed

"Things started changing after that," he said. "The Islamists were given jobs, they became headmasters and officers." They closed the cinema and converted it into a mosque. Art disappeared and gradually women started wearing the full black niqab. "Last year they killed 10 men and threw their bodies in the streets, saying they were homosexuals," he said.

"I agree with George Bush in one thing," Khalid Abdul Nabi, one of the well-known Al Qaida leaders in Ja'ar, said. "He gave us a really accurate wisdom: you are either with us or against us, you are either with Islam or with the crusaders." One of the problems he faced now, he said, was with younger generations of jihadists. When jihadist leaders try to moderate their positions, the young followers will often splinter and form more radical groups, so each generation is more radical than the next.

"The shebab [young Islamists] are part of the Islamic situation in Afghanistan, Somalia, Nigeria and Iraq and jihad is a religious duty, like fasting. But the problem is that most of them, yes they are true jihadists with good intention, they lack the knowledge."

A young commander, Jamal, who is attached to Al Qaida in Yemen had agreed to see me.

Too many tragedies

"There are too many Arabic tragedies, in Iraq, in Chechnya, in Afghanistan and in Palestine, that makes us want to fight in the way of God," he said.

"Look this is how we started. [In 2003], after the outbreak of the Iraq war, Ja'ar became a big training ground for the Saudis going to Iraq. Unlike the Yemenis, the Saudis had no experience in fighting. They were very religious and had lots of money, but they didn't know how to shoot. We started training them. You know we Yemenis are taught to shoot when we are children and then a whole ring was organised to send them to Iraq via Syria."

President Ali Abdullah Saleh's government knew about the jihadist training camps, he said, and had no quibble with them as long as they didn't fight in Yemen. "Saleh told us go to Iraq but not to come back and create problems for him here."

In the winter of 2005-2006, the world began to take note of the flow of jihadists heading to Iraq and the Americans started to put pressure on Syria, Yemen and Saudi Arabia to stem the flow of militants. "The government exposed the ring," Jamal said. "They started arresting people when they reached the border. We started clashing with the government and we killed some of their security forces."

Trust did not last long

In 2006 he was arrested, which led to the first of several meetings with Saleh. Saleh agreed to release the prisoners in return for their promise of inactivity. Three days later Jamal was back on the streets, but trust between him and the government did not last long.

"They put a lot of pressure on us," he said. "I was monitored. You leave your house and there is a government spy. You come back and there are two. So we changed our procedures." When the government arrested some of the jihadists, fighting broke out again. "We fought with them again. We fought the government until all of our brothers were released."

Cycle of arrests

A cycle of arrests, fighting and deal-making ensued, escalating the strength and anger of the jihadists. Sometimes they would be promised compensation by the president, but when they went back to Sana'a to collect the money they would be sent from one government department to the other. Weeks would pass, and so the clashes would erupt again. "Before our last meeting with the president in 2009, Ja'ar fell under our control. By that time, our brothers stopped going to Iraq. They said if we are not arrested on the way and we reach Iraq, either the Americans will arrest us or we would be tortured by the Shiite [Iraqi government]. Why not stay and fight here.

"We entered Ja'ar, and the town fell in our hands. We were more than 40, the police and army left, and we called Allahu Akbar, and planted mines and explosive devices in the streets, and for the first time we went back to our homes and we slept in our beds. We were no longer fugitives, we took over the security of Ja'ar and we imposed Sharia."

A small mouse darted across the floor between our legs. It hit one of the legs and scurried under the bed.

Even this young commander had trouble with the generation of radicals coming after him.

"We were betrayed by the people of Ja'ar," he said. "When we used to hide in the mountains some kids from the town used to come and bring us food and clothes. We trained those kids how to use a weapon, how to wire explosive devices, how to build electrical circuits. They were young kids. We trained them how to attack, how to hide behind a wall."

He clutched an imaginary gun and manoeuvred while he was sitting cross-legged on the floor. "Those young kids started looting and beating up people. They destroyed the town."

His voice became a mixture of blame and regret. "Because of the young, we failed in ruling the town and we had to leave and head back to the mountains."

Even for Jamal, who represents the post-Iraq war generation, there is another generation after him who don't know which government property to loot and which to leave alone, a generation he thinks is unruly.

I asked Jamal if he considered himself part of Al Qaida's organisation in Yemen. "We are all connected, all the jihadists are connected," he opened his arms and pointed at the three of us sitting on the floor. "One of us is Al Qaida," and he pointed at himself, "the other is protecting him," and he pointed at me, "and the other is providing logistics." And he pointed at the teenager who had brought me there.

"The two," he pointed at us, "would only know Al Qaida person they are in contact with, and that Al Qaida person [he pointed at himself] would be the only one in that group to know the leadership."

What Al Qaida gave him, he said, was organisation. "Before Al Wahaishi [the head of AQAP] and Al Reemi [the commander of its military wing] arrived here we were chaotic, we would fight the government whenever we wanted. Now we only move when we are given orders."

Hero to all

As we walked back through empty dark streets I asked the teenage boy leading me how the young looked at people like Jamal.

"He is like a hero for us all, we want to be like him." Why? "Because he stands for his people. He won't let the government do whatever they like."

Speaking to the deputy governor of the Abyan province, I asked him about the meetings the jihadists had with the president and the promised money. He said: "The authority wants to contain those men. They block roads and attack military checkpoints and collect fees from shop owners. Because this is not a state of law, this a state of buying people, they treated the jihadists and Al Qaida in the same way they treated the tribes, they paid them money to lie low."

"You have to understand that the military campaign will cost money, money for soldiers, for vehicles, then money in prison, money for a court case, so the state says why should we pay three million to fight them when we can pay them one million for things to calm down and avoid their evil. But the jihadists take the money, buy weapons and become stronger, and now the state regrets that policy and it is changing."

Update to follow: Ghaith Abdul-Ahad follows the trail of the US' "terrorist No 1", Anwar Al Awlaki

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox