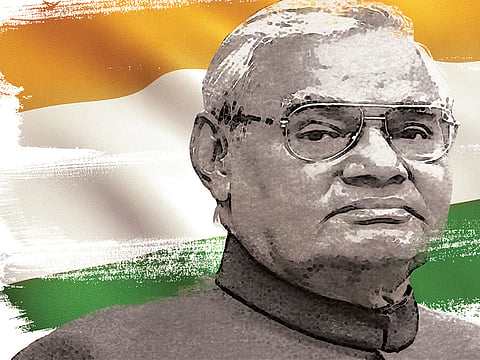

Vajpayee: Politics without taglines

Former Indian PM and BJP stalwart had realised very early in his career that nationalism for the vast majority of Indians isn’t something to be worn on one’s sleeve

A rather grim-looking Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was frantically battling the heat and humidity on Friday — wiping off those stubborn beads of sweat flowing down from his head and face in a never-ending stream. Barely 20 feet away, at Smriti Sthal (spot of remembrance), lay the mortal remains of his party’s behemoth — former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Age finally caught up with one of India’s tallest sons whose half a century-old political career was as steeped in a dignified diligence to sobriety as was his penchant for poetry in personal life.

But coming back to Modi’s sweat-soaked homage to a stalwart on a sultry mid-August afternoon in Delhi. In the wake of the Gujarat riots in 2002, Vajpayee, the then prime minister, had reminded Modi, then the chief minister (CM) of Gujarat, about a public servant’s inalienable accountability and non-negotiable commitment to “Raj Dharm” (duty of the ruler). Telling words, coming from a veteran who had been a part of India’s freedom struggle, who was jailed during former prime minister Indira Gandhi’s draconian assault on democracy in the name of Emergency.

No one will perhaps ever know whether Modi’s mind had raced back to Vajpayee’s sagacious advice, as smoke billowed from the pyre at Smriti Sthal on Friday. But for the vast majority of Indians and for the country’s political class in particular, Vajpayee was that rare breed, that once-in-a-generation occurrence whose becalming influence as a public persona served as an antidote to a squalor-ridden legacy, that momentary glimmer of a shining gem in a cesspool of selfish interests and ugly one-upmanships. His political ambition never let him lose sight of his bigger role as a statesman — nation-building. He never let his ideology play second fiddle to opportunism. His glowing tributes to Indira on the floor of the parliament, in the wake of the then prime minister’s paramount role in Bangladesh’s war of liberation in 1971; his decision to announce a two-year moratorium on all nuclear tests immediately after India’s proud proclamation of nuclear weapons capability in 1998; and most of all, his bus journey to Lahore from the Wagah border in 1999 — in what was the surest sign of New Delhi’s most robust peace outreach to Pakistan since the 1972 Simla Agreement — will all rank among the high-points in Vajpayee’s illustrious journey as a career politician and a statesman par excellence. Even during the Kargil war in 1999, when the temptation to succumb to the demands of jingoism and optics were sky-high, Vajpayee struck a critical balance between prudent diplomacy and a muscular military policy to blunt the aggressors’ propaganda and warmongering.

If the five years of full term as prime minister, between 1999 and 2004, brought Vajpayee the statesman to the fore like never before, then his role as the lodestone for India’s largest Hindu nationalist party — the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) — was no less significant. Vajpayee was one of those few right-wing political heavyweights in contemporary India who had sensed the need to have a strident Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) metamorphose into a more workable template for a pan-India political identity.

His own man

The transformation of the erstwhile ultra-rightist Bharatiya Jan Sangh into the present-day BJP was made possible to a large extent by the Vajpayee brand of politics of consensus and inclusivity. Vajpayee was the foremost Hindu nationalist leader who had realised very early in his career in active politics that nationalism, as the vast majority of Indians see and interpret the concept, isn’t something that ought to be worn on one’s sleeve. Rather, nationalism, and Hindu nationalism in particular, ought to be a way of life that is bereft of all forms of regimentation and indoctrination. It is truly remarkable that for someone who had the ultra-rightist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s (RSS) ideology baked into his DNA, Vajpayee still managed to avoid, with remarkable success, the tag of being an RSS stooge. He was his own man all through his life and career. It is no wonder that with the passage of time, the RSS brand of politics in BJP found greater traction with Lal Krishna Advani, rather than Vajpayee. Even when Advani insisted on his high-optics Rathyatra (chariot ride) to fan the flames of Hindu nationalism and drum up support for a Ram Mandir (temple) at the disputed site in Ayodhya in 1989 — very much in keeping with the RSS playbook — Vajpayee’s reported chilling retort to a Delhi scribe was: “Prabhu (Lord) Ram shall never reside in a shrine based on violence and hatred.”

The exhortations to a sitting chief minister to pledge his soul to “Raj Dharm” and the refusal to join the chorus of “Mandir wohi banaengey” (we’ll build the temple at that very site) bear the hallmark of a son of India for whom it was always “Nation First” — without subscribing to any form of jingoism.

Today, after almost three decades since the 1989 hysteria over Rathyatra, Advani, in spite of all his political acumen and acclaimed literary pursuits, is still a relative lightweight in comparison to a towering lighthouse called Vajpayee. One had conflated Hinduism and Hindutva and paid the price with his political obsolescence. The other had seen the two concepts as distinct in terms of their etymology as they were in their respective lived experiences.

And it doesn’t take a Vajpayee to educate you on the difference between a headline and a side story in history.

You can follow Sanjib Kumar Das on Twitter: @moumiayush.