Giving the gift of joy

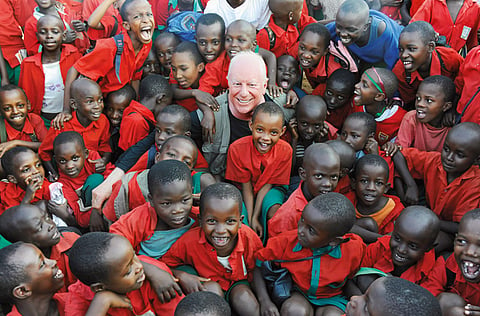

Millionaire businessman, philanthropist and photographer Bobby Sager is putting smiles on children's faces with something as simple as a football

The two pictures are in stark contrast. The first shows a small Rwandan boy, his shoulders drooping, hesitant to look into the camera, dead to the world around him. The other shows the boy grinning with delight as he handles a yellow football. The boy in both pictures is nine-year-old Moises. And the smile on his face is thanks to the gift he received from US-based philanthropist-photographer Bobby Sager.

Now living at a rehabilitation centre in Rwanda, Moises was seven when he was kidnapped and forced to become a soldier during the genocide of 1994. He was one of several kids rehabilitated by Bobby, who apart from taking pictures also organises initiatives to improve the lives of those affected by war or natural calamities across the world.

Moises' transition from boy soldier to normal child can be seen in the book, The Power of the Invisible Sun that Bobby compiled from hundreds of photographs he's taken over the years. They are part of his exhibition on at The One Fusion in Al Quoz 1, running until January 11, 2012.

A successful entrepreneur, a passionate photographer and a keen philanthropist, Bobby was in Dubai earlier this month for the exhibition and to raise funds for his charity, the Sager Foundation.

Bobby is charm personified when it comes to talking about his charity programme, as well as when reacting to what his A-list celeb friends have to say about him. When asked what he thought about superstar musician Sting's remark that "Bobby's a big brash guy from Boston, flamboyant, eccentric, inexhaustible world traveller, and practical philanthropist", his reaction was, "Oh, that's all right. Sting's my best friend, he knows me better than anyone!

"I am considered brash, I know, probably because I spent the last 12 years of my life trying to be an effective philanthropist. I go to some of the world's most difficult places and have to improvise on the ground there figuring out how to make an impact. I suppose that requires a certain amount of brashness," says the 56-year-old.

But more than the brashness, Sting is impressed by Bobby's humanity that is reflected in the amazing images he's taken of children in war-torn countries around the world. Despite the unthinkable violence and destruction in those places, his portraits reveal joy, innocence and strength. In fact so moved was Sting by Bobby's powerful pictures that he decided to use several of his images as a backdrop for the song Invisible Sun onstage during the 2007-8 The Police reunion tour.

Bobby's spent most of the last decade living in some of the poorest and most ravaged parts of the world, initiating dozens of charitable ventures - from lending money to women whose husbands were killed in the genocide in Rwanda, to distributing blankets to victims of the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan, to bringing indestructible footballs to the underprivileged children in Nepal, Pakistan and Rwanda.

The first few millions he made from his bespoke jewellery business were spent travelling around the world with his wife, Elaine. When the money ran out, Bobby went to work for Gordon Brothers Partners, a Boston-based company that he helped expand from a local jewellery wholesale operation worth $10million to one of the largest corporate liquidators in the world worth $6billion. At 45, he was the president and principal stockholder of the firm and in 2009 became the majority shareholder and chairman of Polaroid.

Using money to make a difference

So what prompted him to give it all up to go ‘do some good where it was really required'? "There was no ‘bolt of lightning' that jolted me into philanthropy. The reason is very mundane," he says. "I had a very ordinary childhood. My dad was a salesman making about $300 (Dh1,100) a week. I grew up appreciating what I had and learnt not to take things for granted.

"I see so many rich kids grow up spoilt, feeling entitled and ultimately dysfunctional. So I decided to use my money to show my kids that they could make a difference in the world and to also remind them how lucky they are. I was a successful entrepreneur and had only ever made money. [Making the right business deals] were the choices I made in my life, and after I'd succeeded I decided to make different ones. Elaine and I took our kids, Tess, eight, and Shane, six, out of school and went off to live in places like Nepal, Pakistan and Rwanda, and eventually in Afghanistan and Palestine - to live a fuller life and to give others a better one."

Up close and personal

In 2000, Bobby founded the Sager Family Travelling Foundation & Roadshow. On the very first trip, Bobby's idea of giving his children a taste of real life paid off. "We were in Nepal setting up a series of schools," he reminisces. "It was in December and quite cold. My son was playing with one of the kids there when he asked the kid, ‘Why aren't you wearing your shoes?' When the kid replied he didn't have any, Shane was stunned. For the first time he understood that not everybody has shoes, or electricity in their homes or water to drink."

The Sager family spent about a month sometimes more in each place they visited - Nepal, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Palestine, among others - so they could understand what the people's needs are. "Often I see well-meaning people come into a place and tell the people there what they need instead of spending the time necessary to listen, understand and find out from them what they really need. That's what we've been doing for 12 years now."

Choosing the places to visit has to do with opportunity. "In business I made money because I saw an opportunity," says Bobby. "In trying to make a difference also I seize an opportunity. So we went to Pakistan because there was an earthquake there, to Afghanistan because there was a war; to Rwanda because there was a genocide. In all those places, there was a big opportunity to make a difference.

Bobby started doing his bit for charity 15 years ago, but it was only around 12 years ago that he took up full-time philanthropy - what he calls ‘eyeball-to-eyeball philanthropy'.

"I don't believe in writing a cheque for some distant cause," he says bluntly. "I believe in being hands-on, looking people in their eyes, feeling their humanity, and letting them feel yours. It isn't just helping, it's a way to live life to the fullest. And that's the best return on investment I've ever gotten by a long shot."

Over these years, Bobby and his family have been on 36 trips to various countries. Would all this have been possible if Bobby's wife Elaine - who was his high school sweetheart - and his children been unwilling to lead this kind of gypsy lifestyle? "I am lucky that Elaine and the kids are gung-ho about our lifestyle," he admits. "They could be leading a life of great luxury back in the US if they wanted to. Even if they weren't willing, I would still be doing this, but certainly not have the impact that we have as a family."

One thing that makes even Bobby hesitate is the danger posed to his wife and children in some of the areas they operate in. "We are careful not to take unnecessary risks and so far we've been OK," says Bobby.

The Sagers' time in Afghanistan - they were there three weeks after the September 11 attack in the US - was "educative'', but now it's out-of-bounds for his family. "I don't want to put them in an active war zone," says Bobby. "I am not going there as a thrill-seeker."

Giving people opportunities

What's thrilling for Bobby though is the ‘healing power of the free market' that drives his brand of philanthropy. This ‘healing power' brings about change and empowers people by appealing to individual self-interest. "The common element in our work is that we don't just give out money. We give people opportunities to help themselves," he says.

"Take for instance our work in Rwanda, where almost a million people were murdered in 100 days in 1994. As part of our micro-lending programme, we offered wives whose husbands were murderers in the genocide and were now in prison, sums of money to set up small businesses with women whose husbands were murdered. I wanted to combine micro enterprise with reconciliation. So the widows of the genocide and the wives of the murderers started businesses together, and by serving their self-interest they came together as people, as mothers who wanted a better life for their kids. That's reconciliation by finding common interest, where they understand each other as human beings and everybody gets served."

Bobby looks for what he calls ‘the real return on investments'. "For instance, we train teachers to improve their skills in the North-West Frontier Province in Pakistan because when you train a teacher you multiply the effect of how many students will ultimately benefit. It gives a huge return on investment."

Bobby's fond of subverting popular catchphrases to make his point. Like his explanation of his philosophy: "Take the old parable of teaching a man to fish rather than giving him a fish," he smiles. "Unless you teach him how to sell the fish what's he going to do with all the fish he catches? We have 300 Palestinian women making bracelets, and women making earrings in Rwanda. Unless we teach them to market their products [they are sold in Dubai at THE One], what's the point?"

Among his earlier schemes to get a better return on his money was to sponsor groups of students from countries in conflict through annual scholarships at his alma mater, Brandeis University in Boston. "The idea was that these students would meet each other, develop friendships, go beyond the stereotypes that restrict them. Down the road that would pay off as a really big dividend."

The real deal dividend has been his children. Tess, now 19 and a student at New York University, has developed her own project supporting women's cooperatives in Rwanda and the West Bank by selling their handicrafts through an online shop under the banner "Hands Up, Not Hand Outs". Shane, 17, is still at school and very involved with his parents' work.

"I do all this partly because I'm selfish, my family and I get to live so much life, we learn and experience new things," say Bobby. "The very last line in my book of photographs, Power of the Invisible Sun, says, ‘Be selfish, go help someone'. I am trying to twist the paradigm that you have to be touched by an angel to be giving back to society and all that. That's not sustainable. There has to be something that nourishes you. I've been doing this for 12 years using only my money, I don't take contributions. I want to make a difference, but equally important, I want to live a very full life."

This one's a winner!

"The idea of the indestructible soccer ball was originally brought to my attention by my friend Sting," says Bobby. "I connected with it because of my experience with Moises, a former child soldier living at a rehabilitation centre in Rwanda."

It was Bobby's photograph of Moises that caught Sting's eye. It was a poignant picture of what Moises and the kids in the refugee camps used as a football. Made of bits of rubber and rags, it was Moises' prized possession. So they decided to make them an indestructable ball, something that would last.

For Bobby it's something more: "This ball's a really powerful symbol of hope, it's a symbol of possibilities." Proceeds from Bobby's book pay for the ball project, ‘Hope Is a Game Changer.'

Starry friends

Bobby Sager has friends in high places. But one thing he's very firm about is that he won't use them.

"Friend is a funny word," he says. "Sting is a very close friend of mine. I have a friendship with the Dalai Lama, former President Bill Clinton among others, but I wouldn't describe them as close friendships. I've known both the Dalai Lama and President Clinton for about 15 years. Clinton spent time in my home when he was President. I've been in the home of Nelson Mandela three times, and have visited the Dalai Lama in his home in Dharamsala many times. I don't use my friends to do my charity work. I believe that they are interested in me as a person and in having a friendship with me because of who I am and what I do. I have a programme that the Dalai Lama and I started together 12 years ago, so in that sense we work together. Sting has been with me in refugee camps in Palestine and in villages in Nepal and India. We hope to fund the Nelson Mandela Museum in Cape Town and have done other projects with him. I've been involved in the Clinton global initiative as one of its founding members."