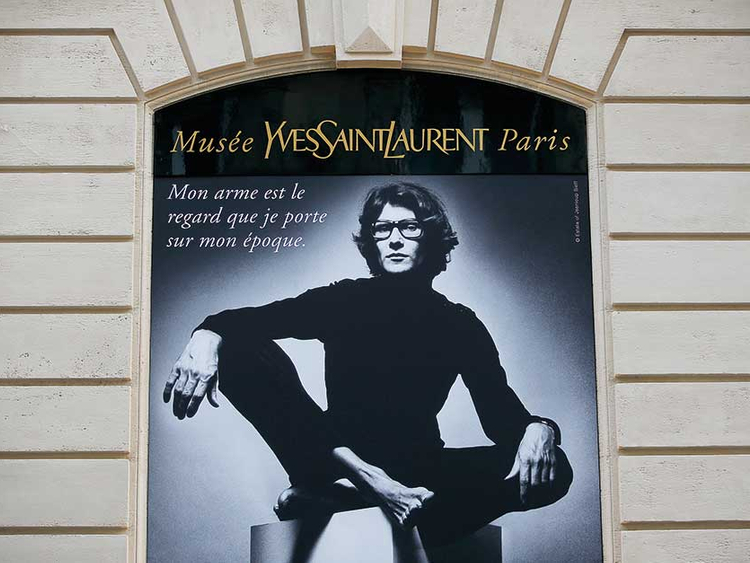

It’s a perfect autumnal morning in Paris. Three letters — YSL — so synonymous now with luxury and glamour, glimmer in the sunlight above the entrance to a three-storey Second Empire mansion house just across the river from the Eiffel Tower. For almost 30 years, this was the couture house of Yves Saint Laurent, the charismatic prodigy who took Paris by storm in his teens and went on to redefine the way women dressed for decades to come. After almost 18 months of renovations, it is now opening as a museum dedicated to his work. As a sign of its importance to the national identity, the minister of culture, Francoise Nyssen, attended the inauguration on Thursday, and on Tuesday, it opened to the public. I was going in for an exclusive preview.

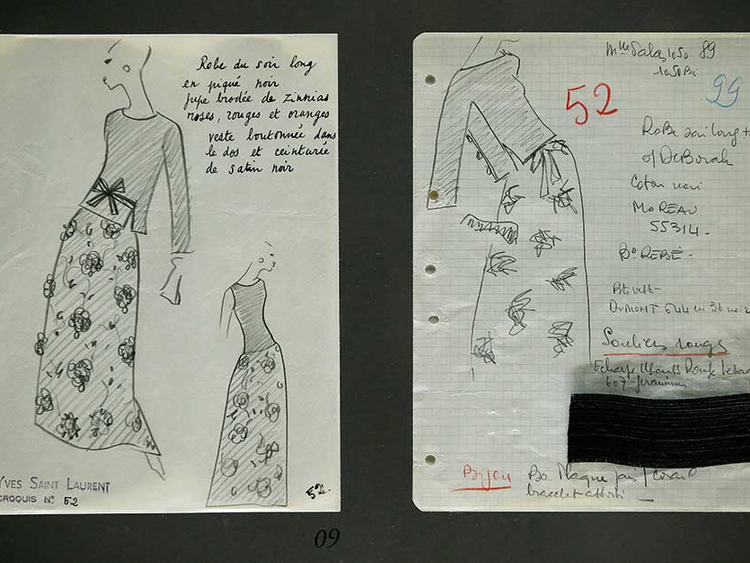

In mannequins and montages, original notes and sketches, videos and voice-overs, the museum charts the Saint Laurent story — from his first groundbreaking show in 1962, through to his designs for ballet and theatre, his fantastical costume jewellery, and his most iconic works including the era-defining “smoking” tuxedo. It’s an extraordinary visual narrative, and one which Saint Laurent himself had anticipated. He meticulously catalogued all his work, and from the ’80s onwards began marking pieces with “M” for “museum”. As a result, the curators are spoiled for choice, with a vast collection of 5,000 garments and 15,000 accessories to select from for the main exhibition spaces.

Designers Nathalie Criniere and decorator Jacques Grange, both long-time collaborators of Saint Laurent, have aimed to recreate the original atmosphere of the haute couture house — all neoclassical columns and burnished statues — and the bulk of the exhibition spaces are located on the ground level, in the salons where Saint Laurent’s wealthy clients would have tried on their custom pieces.

One display features a dozen mannequins adorned in the finery of his first solo collection from 1962, including a naval-style suit with gold costume buttons and a deliciously prim tweed two-piece, complete with looped bow collar. Then there are the others side of his work, the exotic influences that worked in counterpoint to his classic Parisian aesthetic.

A multi-coloured assortment of looks includes his iconic orange “bougainvilliers” cape, covered in iridescent pink, silver and gold petals — a piece he said was inspired by the Majorelle gardens in Marrakech.

Of particular interest to me was the inspiration he drew from art. On the ground level, there is a small room focusing on three painters who influenced his designs, key images placed alongside the corresponding garments — an original of Picasso’s Musical Instruments on a Table, from Saint Laurent’s collection, a projection of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, and work by Mondrian whose iconic designs were transposed onto cocktail dresses for his iconic 1965 collection — a prototype is on display. He and his companion Pierre Berge, who died earlier this month having overseen the creation of the museum, were avid art buyers. Berge famously auctioned much of their vast collection at the Grand Palais following Saint Laurent’s death in 2008.

Upstairs, Saint Laurent’s favourite opera plays through the speakers, a reproduction of the designer’s preferred working conditions. Spotlights illuminate 12 opulent gowns, each one referencing a different period from the history of fashion, from Greco-Roman togas to retakes on the Belle Epoque flapper. “We stop at the ’40s,” the director of collections tells me. “Why? Because from the ’50s onwards, it’s Yves Saint Laurent who made la Mode.”

Overall, it is a small, if artfully put together exhibition. The designer’s pret-a-porter collections are not part of the permanent displays, nor the costumes he designed for cinema, instead these will be featured over time in temporary exhibitions that will replace the permanent display for four months every year (They begin with Yves Saint Laurent’s Imaginary Asia in October 2018).

But we perhaps get the best understanding of the man from his studio, also recreated on the first floor of the new museum. Floor to ceiling windows cast light on a long room, with a mirror wall at the end, which Saint Laurent would use to survey his creations. Joyous details — sketches, coloured pencils, art books, boxes of brooches — evoke a space of creation, collaboration and glamour.

At the end of the room is YSL’s desk, and on the wall behind it, a portrait of him by Bernard Buffet, a black and white photograph of Catherine Deneuve, pictures of his beloved French bulldog Muzhik. The set-up is, Madison Cox informs me, exactly as it was “apart from it’s a little bit tidier — there were rolls of fabric everywhere and his dog running around snipping at models’ ankles.”

Cox, a San Francisco-born landscape designer and a long-time friend of Saint Laurent and, latterly, Berge’s husband, designed the latest incarnation of the Jardin Majorelle. He is now vice-president of the Pierre Berge-Yves Saint Laurent Foundation and is keen to point out the importance of the city in Saint Laurent’s life and work.

“Paris was that mythical place that he wanted to be a part of, the epicentre of French culture.”

And if the museum gives an insight into YSL’s work, you can also trace his life in the city too. He had grown up by the sea — in Oran, in then French Algeria — but by his early teens, his sights were firmly set on Paris; his evenings were spent designing dresses for his paper dolls and drawing up orders for the atelier he dreamed of opening on the glittering Place Vendome. In fact, he ended up a little further west at Christian Dior’s haute couture house in Avenue Montaigne and this is still the heart of the Paris fashion district, with designer stores studding each side of the street — Chanel, Chloe, Fendi, Celine Balenciaga, and of course YSL, now owned by the same group as Gucci, and rebranded Saint Laurent Paris.

His heyday was the ’60s and ’70s — he helped shape the style on the street, but he was also part of the scene, mixing with, among others, Mick Jagger, Catherine Deneuve and Andy Warhol. Many of his haunts are still there: on Avenue Montaigne, the art deco grandeur of the Theatre des Champs-Elysees, where he would attend the latest ballets, and the Le Relais Plaza, at the Plaza Athenee hotel, where he would often dine. “He loved that place,” Cox tells me, “because it was the epitome of French glamour”. Prunier, a discreet, elegant seafood restaurant in the 16th arrondissement, bought by Berge in 2000, was another favourite — today, it is a picture of quintessential French sophistication, where well-coiffed Parisians dine on oysters and converse in muted tones.

Each year, the establishment releases special edition tins of caviar, decorated with designs from YSL’s Love greeting cards. If Saint Laurent’s work as a couturier would be forever yoked to the Right Bank, the second phase of his career was rooted across the Seine in St Germain, the bohemian heart of Sixties Paris. He lived on this side of the river, too. In 1966 he opened Yves Saint Laurent Rive Gauche, the first-ever designer ready-to-wear boutique on Rue de Tournon, behind the Luxembourg Gardens. Though the Rive Gauche boutique is now closed, many of Yves’s old haunts can be found in the area, such as the historic Theatre de l’Odeon and the galleries and antique bookshops of Rue de Seine.

The nearby Cafe de Flore on Boulevard St Germain was where he often met Deneuve, for whom he designed the iconic costumes in the era-defining film, Belle de Jour. From here, I retrace what would have been Yves’s walk home, a 15-minute stroll westwards to the residential 7th arrondissement, in the shadow of the gold dome of the Invalides. The designer’s former apartment on Rue de Babylone faces a couple of sleepy bistros. It’s easy to walk straight past a small stone plaque on the wall. It reads: “Yves Saint Laurent, couturier francais lived in this building”.

The glittering letters of the museum across the river on Avenue Marceau are harder to miss.