ETFs: The new asset class gaining popularity

Investors realise a scarcity of managers who consistently outperform

By Pauline Skypala

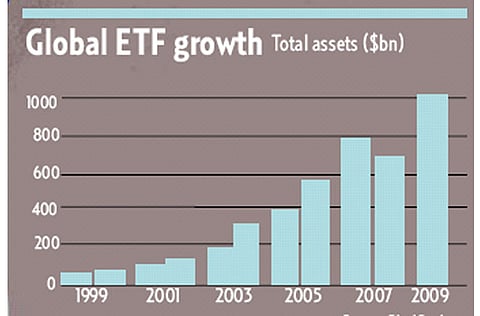

At the turn of the century, exchange traded funds had $40 billion (Dh146.8 billion) of assets under management. Ten years on and that figure has grown to $1.03 trillion, according to data from BlackRock, passing the important $1 trillion marker in December. There is another $154 billion in exchange traded products that cannot be classed as funds.

This is still peanuts in relation to the mutual fund industry, which accounts for about $11 trillion of assets under management in the US and $7 trillion in Europe. But recent sales trends suggest investors are more interested inETFs: a net $94 billion flowed into ETFs in the first nine months of 2009, against $13 billion for mutual funds, according to Strategic Insight.

So are investors deserting actively managed funds in favour of funds that passively track an index, as most ETFs do? It looks that way, but the comparison may be misleading, as ETFs are at least as widely used by institutional as retail investors. In Europe, the split is estimated at 90 per cent institutional and 10 per cent retail, while in the US it is 50/50.

Deborah Fuhr, global head of ETF research at BlackRock, says it is hard to generalise about trends as the US and European markets are so different. But there is no doubt that the events of 2008 led investors worldwide to reappraise products in the light of their exposure to counterparty and liquidity risk.

"During 2009, many investors found that ETFs met their desire for greater transparency," says Ms Fuhr. There is also a growing demand for low cost access to market returns, or beta, as investors become more aware of the scarcity of active managers that can consistently outperform, she adds.

Market development is driven by different factors in different regions, partly because of what the regulations allow. The first ETF in the US appeared in 1993, while the Asian market was born in 1999 and the European one in 2001. So the US had a good head start, and accounts for the lion's share of assets under management in exchange traded products — $793.6 billion against $242.6 billion for Europe and $64.1 billion for Asia.

ETFs also have a bigger share of the investment fund market in the US than in Europe, with 6 per cent playing 3 per cent, respectively, according to figures put together by Source, a European ETF platform set up by Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

Ted Hood, chief executive of Source, says the European industry could be on the verge of a growth spurt that will see ETF market share rising to US levels. ETFs in the US took off as trading products in their 10th year, he says, and potentially the same could happen in Europe. That is interesting from an investment banking perspective, as trading activity is profitable: traders pay commissions and banks make spreads.

Europe trade

Banks see Europe as "kind of dull from a trading perspective", says Hood. "But if you could make Europe trade like the US there is substantial opportunity for growth. Liquidity begets liquidity, which then attracts more assets into the market." In the US, he says, average daily trading volumes for ETFs traded via exchanges (rather than over the counter) are around $70 billion (more than 11 per cent of ETF assets under management). In Europe they are $2.7 billion (less than 1.5 per cent of assets).

Direct comparisons are difficult, though, as there is no requirement to report ETF trades in Europe, as there is in the US. Fuhr says only about one third of trades are reported in Europe. "It makes people trade in the US because there appears to be more volume."

However, she accepts Hood's contention that the fragmentation of the European market is a barrier to growth in the ETF market. He says large European ETF providers typically list their products on every possible exchange.

That maximises asset gathering opportunities, but reduces liquidity, which in turn means trading sizes come down and spreads tend to widen.

The banks behind Source decided that, rather than each launch their own range of ETFs, they would work together to improve liquidity. And most of the ETFs Source has launched are listed on just one exchange, although which exchange is used varies with the product.

There is another point of difference between the markets in the US and Europe that contributes to lower trading volumes in the latter, according to Hood, which is the extent of hedge fund participation. Hedge funds account for 50-60 per cent of trading volume in the US, and the strong growth in ETF assets coincided with that of the hedge fund sector.

"A lot of hedge funds are big users of ETFs in the US," he says. They use them to express views on market sectors, both buying to go long and borrowing to sell short. The process to borrow ETFs for short selling in the US is reliable, liquid and cheap, he adds.

In Europe, there was no such mechanism, so hedge funds used OTC swaps. But swaps are not popular trading instruments, as they are not transparent and involve counterparty risk.

"No hedge fund in the US would ever trade a sector swap. They would borrow an ETF and short it," says Hood.

Hedge funds

So one of the priorities for Source was to facilitate the use of European ETFs for shorting by hedge funds, and it has launched ranges of both European and US market sector ETFs.

The different make-up of the markets is due to a couple of factors. First, investment banks in the US cannot both trade and manage ETFs, so they have settled for market-making and trading ETFs, as that is how they make their money.

In Europe, there are no such regulatory barriers, and there is the additional attraction of Ucits III, the regulatory framework for cross-border funds.

ETFs set up as Ucits III products can use swaps to track indices, which plays to the derivatives expertise and trading capability of investment banks.

There is much debate about the merits of using swaps to provide the returns of an index, rather than buying shares in the constituent companies.

Rory Tobin, head of international iShares business, acknowledges that the use of swaps allows accurate tracking, but defends physical replication, which is the iShares approach, on the grounds of its "superb transparency".

There have been concerns about the counterparty risk associated with swap-based ETFs. However, providers say the exposure is limited by the Ucits rules to 10 per cent maximum, and is usually fully collateralised. Providers such as Source point out that having multiple counterparties reduces the risk further. Wealth managers using ETFs as building blocks for portfolios have differing views.

Stewart Fowler, founder of No Monkey Business, a wealth management consultancy, says the counterparty risk is "probably an acceptable one" but if there is a choice he always opts for ETFs that use full replication.

However, Christopher Aldous, chief executive of Evercore Pan Asset, is not worried, and suggests synthetic ETFs "are the lowest risk of all".

Another area of controversy is ETFs that offer leveraged and inverse exposure to markets. Regulators in the US last year warned that retail investors might not understand how these derivative-based products work.

Further development

There has been less concern in Europe, largely because few retail investors make use of ETFs and sales have been lower.

However, there is likely to be further development in this area. Manooj Mistry, head of Deutsche Bank's db x-trackers UK, says the provider plans to launch a range of leveraged ETFs for institutional investors.

The focus for the coming year is likely to be on active ETFs.

Fuhr is uncertain about the prospects for active funds. Asset managers using ETFs as building blocks would not make use of them, she says, because of the double layer of fees. A plain vanilla active fund that is structured as an ETF "has limited appeal to many of today's users". Some institutional investors prevented from accessing hedge funds may find active funds useful, she says.

— Financial Times

What is an ETF?

An exchange traded fund is an open-ended investment fund that trades on a stock exchange like a stock. It usually tracks the return of an index such as the FTSE 100 or the S&P 500. Most ETFs track an equity index, but a growing number provide access to other asset classes, including fixed income, money markets, commodities, currencies and alternative investments. Last month saw the launch of the first ETF by a hedge fund manager.

Originally, ETFs simply bought the constituents of the underlying index but these days they may also be able to use derivatives to reproduce its return, depending on regulatory restrictions.

How is the price of an ETF set?

The market price of an ETF should be more or less the same as the net asset value of the constituents of the index it tracks.

If for some reason the price diverges from the NAV, authorised market participants or market-makers can deal directly with the fund promoter, redeeming or creating units to bring the price of the fund back in line.

I've heard talk of physical and synthetic replication. What do these terms mean?

As mentioned above, the original ETFs simply purchased the underlying stocks in the index they were tracking. The ETF promoters were mostly asset managers, who were used to managing equities, and mainstream indices were liquid enough that it was easy to buy and sell the stocks as necessary without having an undue impact on the price. This is physical replication.

Then investors decided they also wanted bond ETFs, which often meant tracking indices with a very large number of illiquid securities. This was much harder to do, so ETF managers worked out they could buy a representative sample of securities that would move pretty much in line with the index. This was partial replication.

Finally as investors demanded that ETFs provide exposure to ever more niche or illiquid indices, such as emerging markets or even customised indices, ETF managers in Europe worked out that swaps could do the job.

Instead of buying the underlying stocks and providing that return to the investor, the ETF could enter into a swap with an investment bank that promised to deliver precisely the return of the index in exchange for the return on whatever underlying assets the ETF decided to hold. This is synthetic replication.

In Europe, some providers stick mostly to physical replication while others routinely use swaps. A few use both approaches. In the US, a few ETFs, including the biggest one, the SPDR S&P 500, are not allowed to use synthetic or partial replication because of their structure. Others can use derivatives to manage risk, but only leveraged and short ETFs gain exposure via derivatives.

So which is best?

There is no definitive answer to this.

Synthetic replication is likely to give the most precise replication of the underlying index, but it involves a degree of counterparty risk. If the investment bank on the other side of the swap transaction were to go bust, the ETF might have trouble getting its money back.

To mitigate this, the ETFs are usually fully or almost fully collateralised. This means enough assets are put aside in a separate account to cover the debt that might be incurred if either side of the transaction goes bust.

Physical replication's benefit is its simplicity and transparency — it is clear what the holdings of the fund are.

The choice between synthetic and physical replication depends on circumstances and regulation. Relevant factors might include the liquidity of the underlying index, the reason the investor has chosen the ETF — is it because of its simplicity or does the low tracking error matter? — and the expertise of the ETF provider.

An asset manager is likely to have more infrastructure and experience in minimising the cost of buying and selling actual stocks, while an investment bank's strength is likely to lie in its expertise and access to derivatives.

How much do ETFs cost?

One of the main selling points of ETFs is that they are supposed to be low cost, as with any index product, but that cost can vary significantly from one ETF to another. This cost is usually expressed as the total expense ratio and for ETFs that track mainstream indices is likely to be lower than 0.5 per cent of assets. Less liquid indices will have higher expense ratios. Some ETF managers use revenue from securities lending to reduce the effect of fees.

— By Sophia Grene, Financial Times

The appeal of commodities as an asset class for retail investors has been strengthened immeasurably by the emergence of commodity-related exchange traded products (ETPs) which can be bought and sold as easily as equities, avoiding the burden of storing gold bars or delivering barrels of oil.

About $30 billion (Dh110.1 billion) of new money flowed into commodity-related ETPs in 2009 which proved a banner year for commodity markets when total investor inflows reached a record $68 billion.

Total commodity assets under management (AUM) stood at $257 billion at the end of last year, according to data from Barclays Capital, with assets held by commodity ETPs estimated at a record $91.5 billion.

A growing number of investors are opting for ETPs in preference to structured products or indices such as the S&P GSCI index, which remains the most widely followed benchmark. At the end of the year, assets under management held by commodity indices stood at about $111 billion.

But it is over the past decade that the growing appeal of commodity ETPs becomes clearer, with assets up 914 per cent ($91.5 billion), while structured products AUM have increased 270 per cent ($54 billion) compared with a rise of 19 per cent ($105 billion) for commodity indices AUM, according to Barclays' estimates.

Gold played a starring role for commodity ETPs with inflows of 573 tonnes in 2009, which took total holdings to a record 1,762 tonnes, according to the World Gold Council.

Fearing a deep global recession and further volatility across financial markets, investors sought a haven in gold, while silver, platinum and palladium ETPs also saw huge inflows as these funds provide "easy access to hard assets".

Currency movements, particularly the outlook for the dollar, inflationary pressures and the strength of the global economic recovery should determine whether investor interest in gold remains strong this year. Some analysts caution that redemptions from gold ETPs might increase if the pace of economic recovery improves and the dollar strengthens.

"We expect flows to precious metal funds to slow as investors look for value and divert attention to more volatile commodities, says Christos Costandinides, ETF strategist at Deutsche Bank: "We don't expect extreme outflows from precious metals ETPs (in 2010) but growth rates are likely to be slower than 2009."

Attraction

A key part of the attraction of physically backed precious metals ETPs is that "what you see is what you get" and that counterparty risk — the danger that an investor will lose their money if a bank or fund goes bust — can be mitigated or avoided.

Michael John Lytle, director of marketing at Source, a specialist provider of exchange traded products, says that investors need to understand the structure of the product they are investing in and what this implies about counterparty risk. Lytle also stresses the importance of understanding the efficiency with which a chosen commodity ETP delivers the returns that could be expected from a particular benchmark or individual commodity.

In 2009, crude oil prices rose by almost 80 per cent. However, some of the oil ETPs that invested in the benchmark front-month crude oil contract delivered only single digit returns. A third area of concerns for Lytle is trading liquidity.

He says that it is essential for exchange traded products to have a range of market makers as this tightens bid/offer spreads, whereas structured products offered by some banks often only have one market maker — the originating bank. "There is a rainbow of possible exposures to commodities available via exchange traded products but investors need to be aware which part of the spectrum they are analysing," says Lytle.

Nick Moore, head of commodity strategy at the Royal Bank of Scotland says that the recovery in prices last year was accentuated by investment inflows, and investors' appetite for commodities remains strong.

However, Moore gave a warning: "We expect speculation in commodities to remain a hot topic in the coming years and another spike in prices, akin to that of 2008, would likely prompt the authorities to attempt to further restrict investors' access to commodities."

— Financial Times