HOUSTON: Energy Transfer Partners, the biggest US pipeline operator, has lost hundreds of millions of dollars from delays in the completion of the Dakota Access pipeline. And its standoff with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe over a section running through tribal lands could mean an additional $80 million a month in losses.

But it is not the only one paying a price. For North Dakota’s oil producers, once riding high on production from the booming Bakken fields, it is a new blow, after the plunge in oil prices that has shifted the industry’s activity and focus back to more traditional oil regions.

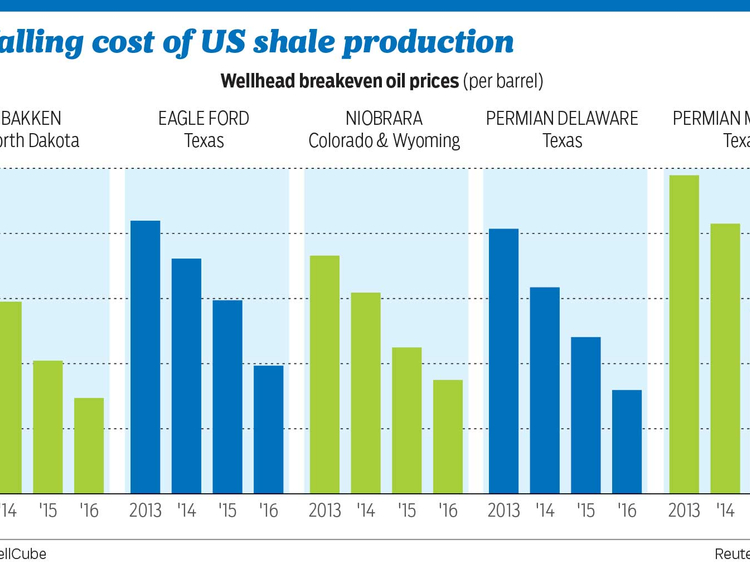

Fields with lower production costs in Texas and Oklahoma have been far more lucrative than North Dakota’s in recent years. The pipeline was meant to give Dakota producers new leverage in the market by reducing their dependence on more costly rail shipments for delivery.

“The biggest loser is the state of North Dakota,” said Ron Ness, president of the North Dakota Petroleum Council. “Companies are not going to get as good a price for their Bakken barrels. It’s a significant impact on their revenues.”

On Sunday, the Army Corps of Engineers cast a new cloud over the project when it said it would not allow a final segment of the pipeline to be drilled under a dammed section of the Missouri River over Sioux protests and would look for alternative routes. The decision could be reversed after Donald Trump takes office, but for now it leaves the project in limbo.

North Dakota’s Bakken field had been at the centre of the shale oil boom that began in earnest in 2011, and oil company executives said the 1,172-mile pipeline would lower costs and help drive up production. Without adequate pipelines, and with slumping oil prices, production in the Bakken has fallen by about a third in recent years.

Bakken producers are forced to ship much of their oil by rail, which adds costs of at least $4 and sometimes as much as $10 per barrel shipped. That created a critical disadvantage for companies like Hess and Whiting Petroleum, which had large stakes in the Bakken. A barrel of Bakken oil now sells for about $1.50 below the US benchmark — $49.77 on Thursday — rarely making it profitable to ship to major markets.

In the meantime, even with oil and natural gas prices in a slump, there has been continued investment and activity in Oklahoma and, particularly, West Texas. Oilfields there have ready access to pipelines, refineries and the growing gas export market in Mexico. As a result, US production levels have fallen less than 10 per cent from record highs more than a year ago.

“We’ve got low-cost oil, and we’re finding new plays all the time,” said Bernard Weinstein, associate director of Southern Methodist University’s Maguire Energy Institute. Nevertheless, he supports the North Dakota pipeline as a way to increase the nation’s oil exports.

Oil company executives argue that pipelines are not only cheaper but also safer than rail transport, citing a variety of fiery train accidents involving oil in the United States and Canada in recent years.

They also note that the Dakota Access pipeline would have the capacity to transport roughly 500,000 barrels of crude oil a day from the Bakken shale fields to refineries in the Midwest, meaning it could be a critical link in coming years if oil prices recover and energy demands increase in a growing economy.

And Energy Transfer, which owns and operates 62,500 miles of pipelines across the country and has a market value of nearly $20 billion, is not giving up on the Dakota Access, which, except for the disputed segment — about a mile long — is almost complete.

“We are fully committed to ensuring that this vital project is brought to completion and fully expect to complete construction of the pipeline without any additional rerouting,” the company, which is based in Texas, said in a statement.

Officials at Energy Transfer declined interview requests.

The company has gone to court to challenge the decision to block the disputed part of the route and to seek alternatives to allay Native Americans’ concerns that the pipeline would cross sacred burial sites and pollute drinking water.

The Trump administration could back Dakota Access, especially given Trump’s selection of Scott Pruitt to head the Environmental Protection Agency. Pruitt, Oklahoma’s attorney general, is a climate change denier and close ally of the oil and gas industry.

Energy experts say Trump might direct the secretary of the Army to reinstate a previous permit for the disputed pipeline segment or issue an executive order granting approval of the entire project. The Republican Congress might also be inclined to support Energy Transfer’s interests.

Those hopes may be why the company’s stock price has climbed since last weekend’s decision by the Army Corps of Engineers to block the route.

If the decision is rescinded, the tribes and environmentalists involved in the protests would most likely go to court. A lengthy legal distraction for Energy Transfer Partners could become a long-running test for the nation’s commitment to fossil fuels — as was the controversy surrounding the planned Keystone XL pipeline connecting Canadian oil sands to Gulf of Mexico coastal refineries. The Keystone XL dispute lasted for years before it was blocked by the Obama administration.

If the Dakota Access fight continued, pipeline proponents might find a friendlier environment in Washington this time.