SINGAPORE/LONDON

The jury is still out over whether an Opec-led production cut aimed at tightening oil markets is working, or if the producer club has simply enabled higher prices without making much of a dent in the global fuel supply overhang.

Analysts say there are early indications that at least some inventories, key in gauging the health of the market, are starting to draw down.

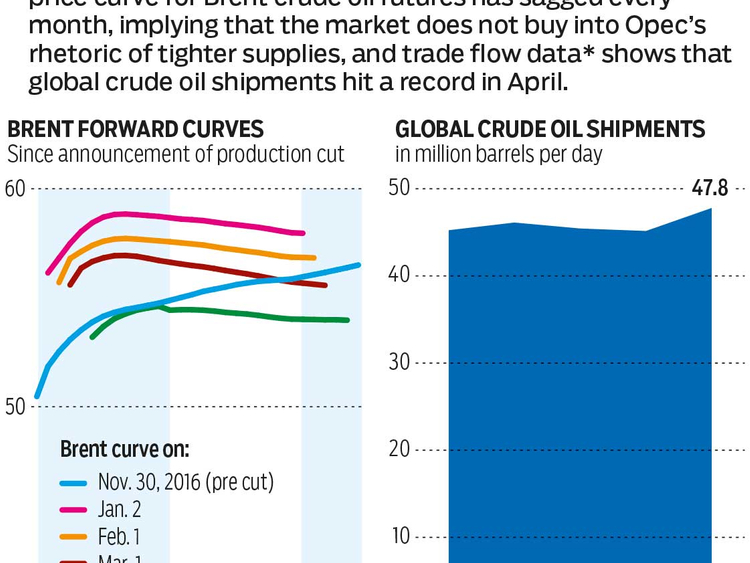

However, inventory levels are hard to judge outside of the United States, as many countries do not release specific figures. Oil shipments show an ongoing excess, while price activity in oil futures suggests sagging optimism the imbalance is being corrected.

Over two years into a 50 per cent price slump, the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec) and some other producers, including Russia, pledged to cut production by almost 1.8 million barrels per day (bpd) during the first half of the year.

But more oil than ever is currently traversing the world’s oceans. Thomson Reuters Eikon data shows global crude shipments, which monitor tanker movements but exclude pipeline flows, hit a record 47.8 million bpd in April, up 5.8 per cent since December, before cuts were implemented.

This is in part due to a jump in production and exports from producers who did not agree to cuts, especially the United States.

“Opec seems more like a magician who is keeping the audience’s attention fixed firmly on his hands (its production policy) while the actual trick takes place elsewhere (non-Opec supply),” said Carsten Fritsch, oil analyst with Commerzbank.

US production is soaring, jumping by almost 10 per cent since mid-2016 to 9.25 million bpd. This brings its output close to the world’s top two producers, Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Futures prices suggest scepticism the market is rebalancing.

Early this year the forward curve for Brent crude futures moved from contango, in which future prices are more expensive than those for immediate delivery, to flat or even briefly into backwardation, suggesting a balancing in prompt markets. This has since reversed sharply.

“If they’re (Opec) so busy complying, how come we’re taking so much extra inventory? Why is the whole curve in free-fall when supplies are supposedly tightening?” said Robert Yawger, energy futures strategist at Mizuho Americas.

Counting barrels

To fully determine the state of oversupply, looking at storage levels is key, but it is not easy. US inventories remain bloated, but outside the United States, it is notoriously difficult to reliably count stored barrels.

There are some signs these harder-to-track inventories are easing. The International Energy Agency (IEA) said crude in less-visible places, such as barrels outside the developed world and those in floating storage, decreased in the first quarter.

But IEA data on the 35 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries paints a more bearish picture.

OECD stocks fell by 17.2 million barrels in March, but since the Opec-led cut started at the beginning of the year, inventories are up by 38.5 million barrels.

“If stocks are still rising strongly, you’ve still got an oversupplied situation,” said Jamie Webster, a fellow at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

“It doesn’t make sense for Opec to pat itself on the back for strong compliance. That’s what they agreed to, not what the impact is.” Some of the oil sloshing around the world could also have been taken out of Opec’s own storage to meet customer demand despite cuts. Saudi Arabian Energy Minister Khalid Al Falih said on Thursday in an interview with the Saudi-owned al-Hayat newspaper that supplies remained elevated in part because traders were selling oil out of tanker storage.

Russia has also been boosting oil exports, despite cuts under the deal.

Millions of barrels of Nigerian oil stored in South Africa’s Saldanha Bay have been sold in recent weeks, and more are scheduled to leave in May.

In Asia, the world’s fastest growing consumption region, many countries, especially China, treat inventory data as strategically sensitive. But trade flows around Singapore, a key way station for virtually all tankers from Europe and the Middle East to Southeast Asia, are a bellwether.

There has been a noticeable drop in crude storage around Singapore this year, although some cautioned these barrels will be quickly replaced by incoming cargoes from the United States and Latin America.