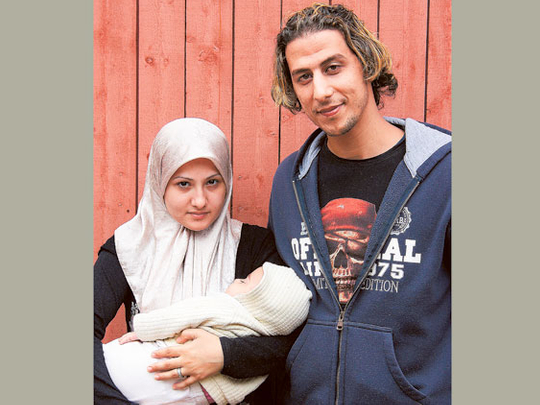

Maersta: Six-month-old Nour Al Hodl smiles, perched on her mother’s knee in the dining room of a spotless refugee reception centre in Maersta, north of Stockholm.

When the Hodl family fled the bombings and violence in the Syrian city of Aleppo earlier this year they had just one goal in mind: to reach Sweden.

This month the Scandinavian nation became the first in Europe to grant residency to all Syrian asylum seekers who managed to make their way to Swedish shores, with the exception of suspected war criminals.

“When we walked out the door of our house in Aleppo we never knew if we’d make it... or if someone would shoot at us,” Nour’s father Khaled Al Hodl said.

But he adds, with a smile, that today he can imagine his daughter growing up to become a doctor.

Sweden is an attractive destination for refugees because “we have a completely apolitical approach to asylum applications in Sweden,” said Fredrik Beijer, head of legal affairs at the Swedish Migration Board.

With one of the world’s most generous refugee policies, Sweden has welcomed tens of thousands of people fleeing dictatorships and wars from Chile in the 1970’s to Bosnia in the 1990’s.

During that time the country developed an extensive reception system for new arrivals, including publicly funded housing, free language courses, job coaching and social welfare payments.

Syrians have been the largest group of asylum seekers in 2013, ahead of refugees from Somalia.

Migration Minister Tobias Billstroem said the increase was understandable.

“The humanitarian crisis in Syria is escalating,” he said. “We should show solidarity.”

According to the Migration Board nearly 11,000 Syrians have obtained asylum in Sweden since 2012 and the figure is expected to rise.

With its international reputation as a haven for those fleeing violence and persecution, it is perhaps unsurprising that Sweden has become the top western destination for Syrians along with Germany.

But Sweden stands out, even when compared with its liberal Scandinavian neighbours.

Despite having similarly generous refugee policies, Norway has taken in less than a thousand Syrians since 2012 and Denmark only slightly more - although the Danes recently decided to accept all Syrians fleeing the worst-hit areas.

The Swedish approach, however, is in line with its ranking among the world’s top foreign aid donors and its vocal support for people’s right to asylum when their lives are threatened.

“My sister, Imam, has been living in Gothenburg for the last two months,” Hodl said.

“We had heard that Sweden gives residence permits to Syrians and Imam was suffering from psychological problems caused by the war. All the family chipped in to get her to Sweden.”

During the 2000’s Sweden took in more Iraqi refugees than any other Western nation, reaching a peak of 18,559 in 2007.

Most of them converged on the town of Soedertaelje, near Stockholm, which has experienced a severe housing shortage, made worse recently by the arrival of thousands of Syrians.

Sweden’s migration policy is not without critics - not just from the anti-immigration Sweden Democrats party, but also among centre-right parties - who have argued that new arrivals should learn to fend for themselves.

They point to persistently high unemployment among refugees, even years after arriving in the country.

That is a fate that Hodl hopes to avoid.

When his cybercafe was destroyed in a bomb attack he and his 17-year-old wife Walaa decided Aleppo no longer offered them a future.

The couple sold their home to raise the 4,000 euros ($5,410, Dh 19,868)) they needed to pay people smugglers to get them out of the country.

“A smuggler got us across the Turkish border along with 90 other people and then they took all our passports,” he said.

From there they travelled to the Turkish city of Izmir where they boarded a flight bound for Germany, armed with fake Belgian passports, which they later destroyed.

“In Germany we changed planes and there was no problem. It was the same when we got to Sweden. The plane landed, I took our suitcase, and we walked out with our baby.”

That suitcase now stands in one of 18 non-descript rooms in the Maersta refugee reception centre, just a few miles from Stockholm-Arlanda airport.

In less than 48 hours after their arrival the couple had applied for asylum and was looking forward to a new life in Sweden.

“We want to live here and get Swedish nationality,” said Hodl.

“I can work at any job but first I need to learn Swedish.”

Until then the Migration Board has provided the family with an allowance of 18 euros ($24.37) per day.

They said their first priority would be to buy some warm clothes.