In Niger, child marriage on rise due to hunger

One out of every three girls in Niger marries before her 15th birthday

Hawkantaki, Niger: Each day before the reaping, the 11-year-old girl walked between the stunted stalks of millet with a sense of mounting dread.

In a normal year, the green shoots vaulted out of the ground and rose as high as four meters, a wall tall enough to conceal an adult man. This time, they only reached her waist. Even the tallest plant in her family’s plot barely grazed her shoulder.

Zali could feel the tug of the invisible thread tying her fate to that of the land. As the world closed in around her, she knew that this time the bad harvest would mean more than just hunger.

In Hawkantaki, it is the rhythm of the land that shapes the cycle of life, including the time of marriage. The size of the harvest determines not only if a father can feed his family, but also if he can afford to keep his daughter under his roof.

Even at the best of times, one out of every three girls in Niger marries before her 15th birthday, a rate of child marriage among the highest in the world, according to a UNICEF survey.

Now this custom is being layered on top of a crisis. At times of severe drought, parents pushed to the wall by poverty and hunger are marrying their daughters at even younger ages.

A girl married off is one less mouth to feed, and the dowry money she brings in goes to feed others.

“Families are using child marriage, as an alternative, as a survival strategy to the food insecurity,” says Djanabou Mahonde, UNICEF’s chief child protection officer in Niger.

This drought-prone country of 16 million is so short on food that it is ranked dead last by international aid organisation Save the Children in the percentage of children receiving a “minimum acceptable diet.”

The consequences are dire. A total of 51 per cent of children in Niger are stunted, according to a report published in July by Save the Children. The average height of a two-year-old girl born is around eight centimetres shorter than what it should be for a child that age. In the tiny village of Hawkantaki, nearly every household has lost at least one child to hunger or the illnesses that come from it. Their miniature graves dot the hamlet. Nana Abdou’s one-year-old brother, who died of hunger last year, is buried in a corner of the animal pen. Soon after his death last year, her family accepted the dowry. Twelve-year-old Nana is engaged to be married before the end of the year.

“Our problems started a long time ago, but every year it’s gotten worse,” she says. “The fathers are marrying off their daughters to reduce their overhead... He’s obliged to if he wants to reduce the number of children he has to feed.”

The numbers tell the story in Hawkantaki, population around 200.

Last year, before the start of the harvest, there were 10 girls in Hawkantaki between the ages of about 11 and 15. By spring of this year, seven were married, and another two are engaged.

That’s a rate of 90 per cent, three times the national average.

None of these girls had “done her laundry” yet, the local euphemism for a woman’s menstrual period. And every single one says hunger hastened her marriage.

The youngest is Zali, a whisper of a girl, whose waist is so tiny you can almost encircle her with your hands. She has no breasts to speak of. Her voice hasn’t broken yet.

Seen from the sky, the village of Hawkantaki looks like a brown dot on a sheet of neon green.

The houses of hand-patted mud are built around a village square. Zali’s faces the northern side. It takes exactly 36 seconds to walk from her door to that of her best friend Aisha, directly opposite on the southern side. Aisha’s cousin Rama lives on an alleyway leading off the square. So do their friends Marliya, Sarey, Shoubalee, Sadiya, Shamseeya, Rakhiya and Nana, all aged between 12 and 15.

“You can’t say Zali’s name without saying Aicha in the same breath, or Aicha without Marliya, or Marliya without Sarey,” said Aicha’s mother, Habsou Daouda. “These girls are inseparable.”

There are no calendars on the walls. Instead of months, they count “moons.” Years are remembered in terms of harvests. Ages can be calculated by the events that happened at the time of a person’s birth.

None of the girls own watches, or cell phones. They have never seen a computer, surfed the Internet or sent a text message. The village has only one light bulb, and it’s strung to a tree, powered by a generator.

There isn’t a single television in Hawkantaki. For special occasions, like a wedding, they rent one, and bring it in strapped to a donkey.

Since birth, the lives of these girls have followed a nearly identical trajectory. They first went out into the fields strapped onto their mothers’ backs. As girls, they played with sticks, raking their “hoes” in the same rhythm as their mums. By the time most kids are learning to hold a pencil, they have become so adept with a real hoe that the space between their thumb and forefinger is already as hard as leather.

On the day of the reaping last fall, the young girls cut the millet and ripped off the leaves to reveal the husk. They bundled the cattail-shaped husks together with pieces of leaves as twine. Then they carried the bundles back on their heads.

Inside each of their courtyards, they pounded the husks in wooden bowls. But the upbeat, cheerful rhythm of the pounding soon slowed down, as they ran out of millet.

Pennisetum glaucum, the variety of millet cultivated in Niger, originated in western Africa and has been grown here since prehistoric times. It’s also known as “pearl millet” for its ovoid grains, which are larger than those of many other cereals grown in the region. The plant is hardy, offers some protein and is known to be resistant to drought.

But even pearl millet cannot survive the repetitive droughts that have pummelled the Sahel in recent years. Zali’s family’s fields failed to produce in 2005, in 2008 and in 2010. Last year marked the fourth drought in the 11-year-old’s short life — an occurrence that used to happen once every decade.

In a good year, her stepfather’s four hectares yielded 150 scoops of millet, the size of soup bowls. At the end of the harvest last year, he counted just 17.

It was the same in all the households. Fields that should have produced 50, 100, even 200 scoops of millet yielded five, 10 or 20. The land had failed all of them, and not a single family in Hawkantaki had anything left over to put in their granary.

It’s like waiting all month for your salary, and then spending it in a few days. Except they had waited all year. And the next payday was another year away.

“The millet last year only came up to 30 per cent of its normal height. There was only one rain. The second one didn’t come,” says 50-year-old Dadi Djadi, Zali’s stepfather.

“It was a catastrophic harvest.”

The missing buttons on Djadi’s aging safari suit show glimpses of his stomach. It’s not just flat. His stomach drops inside of him, as if to mark a hole.

It was soon after, in the emptiness that followed the harvest, that the visitors started to appear.

The groups of older men, wearing skullcaps and robes down to their ankles, came in groups of threes and fours. They said ‘Assalamu alaikum.’ And they asked to see the fathers of the girls.

Sadiya’s father was the first to say yes, accepting around $100 (Dh367) as the dowry. It’s half the amount usually offered, but her desperate family accepted. A crippling hand infection meant her mother could no longer work even as a day labourer in other people’s fields.

Marliya’s father also said yes to the same pitiful amount. So did Sarey’s. Aicha, Zali and Rama’s fathers were offered around $200 (Dh734).

Rama’s father immediately spent half the money intended for his daughter at the market, buying a bag of millet, salt and the vegetables whose taste they had forgotten.

Most of the marriages should be illegal under Niger’s law, which states that the minimum age of marriage is 15. The law, however, only applies for civil ceremonies officiated by the state. Marriages in villages are sealed inside mosques and fall under what is called “traditional law.”

The parents of the girls say they were “ready” and of “marriageable age.” When pushed, some acknowledge they would have liked to wait, and circumstances forced the marriage.

Most of the girls say their older sisters already had their periods before they got married. But no one asked the girls for their opinion.

When the girls walked to the well, they could hear the boys gossiping about them. They made lewd jokes about what was going to happen next.

Around October last year, Zali heard her name and the word “armey,” marriage, and her face felt hot. She came home and started crying. Her mother asked her what was wrong.

“People outside are saying that I’m going to get married,” she said.

Her mother nodded.

On the day of Zali’s wedding this January, she wore a new pagne, a wraparound skirt. It was one of the few items bought for her with the $200 dowry given to her father. The other item was a veil, the kind worn by married women. She was now 12-years-old.

There was barely any food at the wedding.

Her family borrowed a bullock cart to take her to her husband’s home. Her girlfriends piled in with her, laughing. At the door, Zali was lifted onto the back of an old woman who carried her across the threshold, in an ancient marriage tradition.

The mud-walled room had been built by hand by her husband. He is supposed to provide the roof over her head.

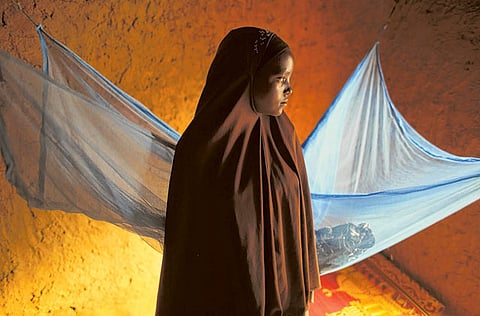

The bride in turn is supposed to provide the furnishings, bought with the cash dowry. In the four months since the engagement, however, Zali’s family had spent almost all of it on food. All she found in the room was a yellow-and-orange plastic mat, a mosquito net, and a few bowls.

According to the local custom, the bride’s friends stay with her for a week. The nine girls sat on the mat on the floor with Zali, singing songs, telling stories and giggling. Each time her husband approached, they shooed him away, clapping their hands and throwing things at him. It was like a game.

And then the week was over, and the 12-year-old girl was suddenly left alone with a 23-year-old man.

When a marriage is consummated, the bride cooks a special meal and returns to her family’s home for the first time since the wedding.

Marliya served her parents the meal after her first night alone with her husband.

The 14-year-old bride was asleep on a sheet of plastic when he came in. Her family had spent her entire dowry, not even leaving enough for a $10 bed mat.

He closed the door of corrugated tin. She tried to run, but he grabbed her arm and twisted it, until she fell back onto the floor.

When he left, she pulled on her veil and ran to complain to her older sister. “This is what he did to me,” she said, twisting her arm in mid-air.

Her sister told her that was normal, and sent her back to her husband’s house.

The next day, she asked her in-laws for food for her parents’ meal. All they could give her was a cup of millet. The dish is served with a meat sauce, but these are hard times in Hawkantaki, and no one can afford meat. So Marliya pounded the green-hued grain and served it to her parents plain.

And so it was for the other girls, sooner or later.

Rama’s marriage began with humiliation, because her father had spent every penny of her dowry. Too ashamed to bring his daughter to her husband’s house empty-handed, he absconded the day of the ceremony and has not been seen since. At first, the 14-year-old pushed her husband away. She gave in after a few days, because she did not want to seem ungrateful to the in-laws who had bought her mattress.

Sarey came down with a fever on her wedding day. They still made her go. She ran away a dozen or more times, until she too made the meal.

Zali fought for a month. At night, her husband tried to touch her. She pushed him away. It was like this the second night. And the third. Weeks passed. It was then that her mother-in-law took her aside to dress her down.

That night, Zali lay down on the mat in her unlit hut. He said nothing when he came in. He just opened her legs.

The next day, Zali’s mother walked into the barren fields that radiate outward from the village. She found the kalgo tree.

All over Niger when the millet runs out, desperate families are reduced to boiling its leaves for food. Her mother went to collect the leaves for a different reason, because they are also known for their anti-inflammatory properties, and are prescribed for new brides.

Zali’s mother boiled them and prepared compresses to soothe her daughter’s crotch.

So many mothers went to pick the leaves this spring that hardly any were left on the denuded branches of the tree.