Academic and diplomat takes on Erdogan

Ihsanoglu faces the challenge of confronting a party that has never lost in national elections

Antalya: By next week, a 70-year-old Turkish scholar and diplomat faces the challenge of his life: besting a political party that has never lost a national election.

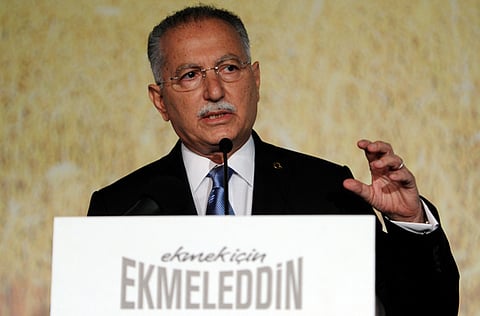

It is a task next to no one expected for Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu, the soft-spoken opposition candidate who will stand against Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey’s prime minister, in the country’s first ever presidential vote on August 10.

As he travels the country with a bus full of opposition politicians, Ihsanoglu is running up against the formidable electoral machine built by Erdogan and his ruling Islamist-rooted AK party, which has won every national contest since its 2001 formation.

The opposition candidate’s key message to voters is that, if he fails in his task and Erdogan wins the presidency, Turkey faces political crisis at home and the risk of greater isolation on the world stage.

While the prime minister, often criticised for his allegedly divisive approach to politics, wants to establish an activist, executive presidency, Ihsanoglu says such an outcome would “not be a democracy but something different”.

He says it is particularly important that Turkey’s president remain “neutral” now that the post will be directly elected for the first time, with a mandate to rival parliament.

“You need a person who would not overstep his authority,” Ihsanoglu tells the Financial Times. “The place where politics should be done - and this is how it has been for decades in Turkey - is parliament.”

He has pointed out that a previous clash between Turkey’s president and prime minister, in 2001, helped precipitate a devastating financial crisis and argues that Turkey’s economy is not currently as strong as the government depicts.

Ihsanoglu, an ingenu politician, never sought the presidency. But his resume commended him as the joint candidate of a cluster of opposition parties, including the two biggest, the secularist Republican People’s Party and the Nationalist Movement Party.

His nine-year stint at the helm of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, an inter-governmental body, and his background as an Islamic scholar were also seen as an opportunity for his secularist backers to look beyond their base to match Erdogan’s appeal to Turkey’s often pious masses.

But the obstacles he faces are formidable. Ihsanoglu relies on a pair of campaign buses and seats on scheduled flights to get to his campaign events. By contrast Erdogan has enjoyed the advantages of office for more than a decade, and is hugely favoured in media coverage, particularly on television.

While the barnstorming prime minister is often hailed as a campaigner of genius, the still-little known Ihsanoglu can appear diffident, reluctant to descend from the bus to address the huddles of well-wishers and eschewing large-scale rallies altogether.

On a recent stop in Antalya, a prosperous Mediterranean resort where he must pile up the vote if he is to force Erdogan to a second round vote on August 24, he was met by more affection than excitement. Plunging into the city centre, he gave no stirring speech, just a near-inaudible statement to a cluster of microphones.

Meanwhile, members of his entourage fretted that Ihsanoglu was receiving uneven support from the coalition behind him, benefiting from the secularists’ political machine but with less backing from the nationalists, some of whose voters may defect to Erdogan.

Ihsanoglu also maintains that Turkey’s ties with the rest of the world are in a parlous state. Relations are strained with much of the Middle East, including Israel, Iraq, Egypt and Saudi Arabia, while ties with western allies have also cooled.

“Turkey needs a better foreign policy and the world needs a better Turkish foreign policy,” he says. “Our relationship with the world should be based on mutual respect and mutual interest, not ideological bias.”

Ihsanoglu adds that he does not believe recent polls showing Erdogan with more than the 50 per cent support necessary to avoid a second round run-off vote and contends that his support is closing on that of the prime minister’s.

Erdogan has lampooned his polyglot opponent by calling him “mon cher” - depicting him as a member of a rarefied elite that has little contact with ordinary Turkish people. Indeed, Ihsanoglu was born and educated in Egypt, where his Islamist father lived after the establishment of the secular Turkish Republic.

By any reckoning, he has a mountain to climb and just days to do it. But, Ihsanoglu says, the voters he meets are desperate for what he offers - an idiosyncratic mixture of “change” and “stability”.

As for his own part in the campaign, he sounds almost resigned: “There are certain challenges you have to take in life.”

— Financial Times

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox