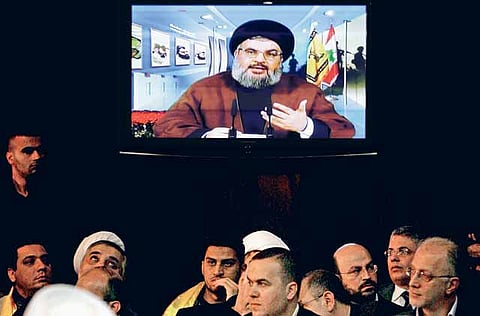

Hezbollah buffs up its nationalist credentials

Nasrallah's call to pay electricity bills and obey traffic rules seen as new tack

Beirut: The leader of Lebanon's Shiite movement Hezbollah recently delivered an odd but deeply important political message to his followers: Heed traffic signs and pay your electric bills.

The call may not seem particularly significant, but it was widely seen as the latest sign that Hezbollah — long considered mainly as Iran's arm in Lebanon running its own state-within-a-state — is reinventing itself as a more conventional political movement in Lebanon.

The group remains fiercely anti-Israel and is highly unlikely to give up its extensive arsenal of rockets and other weapons. Hezbollah's leader Hassan Nasrallah gave a fiery speech on Tuesday vowing to rocket targets deep inside Israel, including Tel Aviv's Ben Gurion Airport, if Israel's military strikes Lebanese infrastructure.

But despite the tough talk, Hezbollah seems more concerned these days with its position at home, trying to show it can work with Lebanon's many other factions, some of which oppose any military entanglement with Israel. That means moderating its actions and playing within the system.

New image

The shift was forced by the seismic events that had shaken Lebanon over the past few years, analysts say.

In particular, Hezbollah's 2006 war with Israel and 2008 sectarian clashes with political rivals raised criticism among some Lebanese that the movement was dragging the country into violent conflicts. Moreover, Hezbollah now has a place in a fragile national unity government, putting further pressure on it to stay in line.

Notably, Hezbollah has not carried out a single rocket attack into Israel since the 2006 war. It has also yet to avenge the assassination of its top military commander, Emad Mughniyeh, who was killed in a 2008 car bombing in Damascus that was widely blamed on Israel. Nasrallah on Tuesday repeated pledges that revenge would eventually come.

Hezbollah "is emphasising that it also has other roles to play besides the resistance," said Amal Sa'ad Gorayeb, an analyst specialising in Hezbollah. The group is trying to highlight its "nationalist dimension" as opposed to its strictly Islamic or Arab identity.

A key step was Nasrallah's announcement in November of the group's platform, only the second since Hezbollah was founded in 1982 following Israel's invasion.

The new language was strikingly conciliatory. While the group's first platform, released in 1985, called for establishing an Islamic republic in Lebanon, the new manifesto does not mention an Islamic state and underscores the importance of coexistence among Lebanon's 18 religious sects.

It also speaks of a "consensual democracy" and says it seeks a "sovereign, free and independent" Lebanon with a strong state that preserves public liberties.

"One of the major aims behind this manifesto is to firmly entrench Hezbollah as a Lebanese movement... to codify it as a Lebanese party par excellence," said Sa'ad Gorayeb.

Hezbollah has also shown hints of trying to shed its state-within-a-state image.

In a December 23 speech on a Shiite holy day, Nasrallah told supporters that heeding traffic laws and paying electric and water bills to the government was a religious duty. Many in its south Beirut stronghold of Dahiya have long been accused of simply stealing from electricity cables and water systems.

Hezbollah also enlisted the help of police and municipal authorities to take down illegally built shops, booths and apartments in Dahiya.

Nasrallah makes his support for the Iranian regime clear. But to boost its domestic legitimacy, Hezbollah "has recently taken great pains to publicly distance itself from Iranian patronage," a 2009 report by the US think tank Rand Corp. said.

Not everyone is impressed.

Sami Gemayel, a right-wing Christian lawmaker, accused the group of "waging a cultural war" on the Lebanese.

Since it was founded at the height of Lebanon's civil war, Hezbollah has grown into one of the most robust, organised and sophisticated resistance groups in the world with a small army of about 6,000 fighters. With an annual budget of more than $100 million largely supplied by Iran, it also runs a network of schools, charities and clinics, and has its own satellite television and radio stations.

Since Israel withdrew from south Lebanon in 2000 — removing the main motive for its armed struggle against Israel — Hezbollah's opponents in Lebanon have grown bolder in demanding it relinquish its weapons and in criticising it as a rogue element in Lebanon.

Hezbollah has "found it necessary to try and alter its image as an autonomous, self-sufficient group that is above the law," says Sahar Atrache, a security analyst for the Brussels-based International Crisis Group.

The 2005 assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri sparked major turmoil and led to the withdrawal of Syria, a major Hezbollah backer, from Lebanon.

A year later, Hezbollah fought a fierce war with Israel in which more than 1,400 Lebanese were killed and large parts of the Shiite south and infrastructure across the country were devastated by Israeli bombardment. Some in Lebanon blamed Hezbollah for providing the spark for the month-long war by capturing two Israeli soldiers in a crossborder raid.

In 2008, Sunni-Shiite clashes brought Lebanon to the brink of civil war before a political settlement was reached.

Hezbollah now has two Cabinet posts in a national unity government between pro-US parties and the Hezbollah-led opposition. Hezbollah also holds 11 of parliament's 128 seats and has an alliance with the Christian Maronites of Michel Aoun's secular Free Patriotic Movement.

Growth: Sophisticated resistance group