Philippines eyes 'mayor economy': Can one-province, one-freezone work?

How local government units (LGUs), given the legal mandate, could propel country forward

Manila: What if the key to unlocking the Philippines’ development isn’t just in national policies — but in letting cities and towns compete like startup companies?

This is the essence of the so-called “mayor economy" — a model of governance that puts a premium on risk-taking and innovation at the local level.

What is a 'mayor economy'?

It's where local leaders are incentivised to act as innovators, like CEOs or managers driving growth through a nationally-sanctioned competition.

It’s a strategy that helped propel China from agrarian poverty into one of the world’s leading economies — and it’s one the Philippines could adopt to leapfrog toward inclusive progress.

Competitive “municipalism”: A blueprint

In the 1980s and 1990s, China’s central government gave local governments autonomy to experiment with reforms, especially in Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and industrial cities.

These municipalities competed for investments, infrastructure funding, and public recognition, according to Harvard and LSE economist Dr Keyu Jin.

“The ‘mayor economy’ makes sense,” Jin says.

The result? Cities like Shenzhen went from fishing villages to tech metropolises. Successes were scaled nationally; failures stayed local.

This decentralised dynamism — instead of a "top-down" control — became the engine of China’s rise.

The proposal to create at least one free economic zone (freeport or ecozone) per province in the Philippines has gained traction in recent years as part of a broader strategy to decentralise development and promote regional growth.

What is a freezone?

A freezone (also called a freeport or economic zone) is a special area within a country where business and trade laws differ from the rest of the nation.

These zones typically offer:

Tax incentives (e.g., income tax holidays, duty-free importation)

Simplified import/export procedures

Faster business registration

Infrastructure support

They are regulated by the Philippine Economic Zone Authority (PEZA) or other special authorities like SBMA (Subic), CDC (Clark), or AFAB (Authority of the Freeport Area of Bataan).

What’s being proposed?

Some lawmakers and economic planners are pushing for a “one-province-one-freezone” policy to:

Spur job creation and industrial development in underserved areas

Reduce over-reliance on Metro Manila and nearby regions

Attract foreign direct investment (FDI) to rural provinces

What’s stopping them?

This policy would require new legislation or executive orders to authorise and fund ecozones across all 82 provinces comprising the Asian nation.

If the Philippines empowered mayors or governors to compete in GDP growth and job screation, the country’s 1,600+ local government units (LGUs) could become laboratories of innovation rather than bottlenecks of bureaucracy.

What is the current situation?

The Philippines, a vast and mineral-rich archipelago in a pond with more than 3.3 billion inhabitants (East Asia), only has 12 SEZs or "free port" areas.

By comparison, Dubai (with a land area smaller than Philippine province of Camarines Sur), has 26 free zones operating. It started with Jebel Ali Free Zone (JAFZ, in 1985), the UAE's first free zone, to the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC, 2004).

In the Philippines, the free zone locations are defined by Manila. Too bad, if you don't have one.

Philippine mayors leading the charge

Despite the limits, some Filipino mayors are already proving the promise of this model.

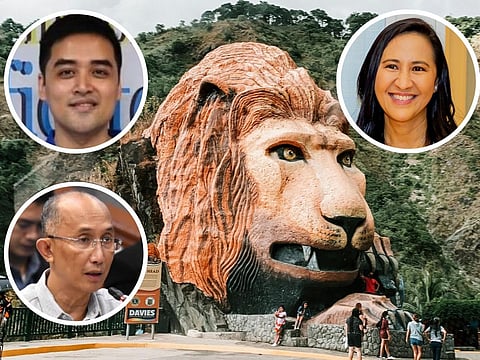

Take Benjamin Magalong of Baguio, Joy Belmonte of Quezon City, and Vico Sotto of Pasig — each one showing how empowered, performance-driven leadership can transform local governance.

Benjamin Magalong (Baguio): The technocrat mayor

A former police general-turned-city-executive, Magalong brought a data-driven approach to public governance.

His administration prioritised urban planning, environmental rehabilitation, and digital governance.

Under his leadership, Baguio launched smart city initiatives and took bold steps against corruption in the public market system.

His style shows how discipline mixed with civic innovation can yield real-world results.

Joy Belmonte (Quezon City): The big city reformer

Leading Metro Manila’s largest city, Belmonte has leaned into social services reform, disaster preparedness, and gender inclusivity.

Under her watch, Quezon City (the country's richest city) pioneered innovative health and welfare programmes during the pandemic and promoted green building codes.

She demonstrates how metropolitan governance can work when mayors focus on sustainability and social equity.

Vico Sotto (Pasig): The reform icon

Sotto represents a new generation of leadership: young, tech-savvy, and allergic to political dynasties. No project accomplished in the city under his watch bears his name or initials.

In 2019, Vico ended the 27-year hold of the Eusebios on Pasig. It’s a city that works today: His commitment to transparency, participatory governance, and anti-corruption has become a model nationwide.

By digitising transactions, publishing city budgets, and dismantling inefficient bureaucracies, he’s proven that good governance is good politics.

He shuns displaying his face or name in larger-than-life tarpaulin banners ubiquitous in other parts of the country.

Local Government Code of 1991

Under Republic Act 7160 (LGU Code), local executives in the Philippines are granted wide-ranging powers, including:

Administrative oversight (supervise local offices, services, and personnel, appoint certain local officials and employees); financial management (propose the annual budget, approve disbursements within legal parameters), emergency powers (during disasters, may declare a state of calamity and mobilise resources), law enforcement (maintain peace and order, oversee local police, under national PNP structure).

Local executives also have a say in economic development, though it's limited to pomoting investments, tourism, and partnerships, grant local business permits and licenses.

No 'free zones' by mayors, governors

Under current rules, Philippine town or city mayors and provincial governors cannot create an economic freeport zone on their own, without approval from the central government.

Why Not?

A number of limitations are set:

Economic freeports and special economic zones (SEZs) are created by national law and/or presidential approval,

Economic freeports and SEZs are considered "national policy instruments" established by congressional legislation,

A SEZ (in every region or province) is possible only with the endorsement of 24 senators or 300 or so members of the House of Representatives, as well as by presidential approval.

(e.g., Subic Bay Freeport Zone, under RA 7227) and presidential proclamations (based on laws such as RA 7916 or the CREATE Act).

These require coordination with national government agencies, including:

Philippine Economic Zone Authority (PEZA)

Bases Conversion and Development Authority (BCDA)

Bureau of Customs,

Department of Finance, and others.

In short, under the current model, it's a national policy to limit these instruments to certain areas (Clark, Subic), relatively close to Manila.

Limits on Philippine mayors

Under the Local Government Code (R.A. 7160), mayors and local executives in the Philippines do not have the authority to grant tax exemptions, customs privileges, or immigration privileges —essential features of a freeport zone. In sum:

Mayors and governors can...

Propose economic development programmes

Create local economic enterprises

Work with investors and developers

Mayors and governors cannot...

Unilaterally establish zones with national-level tax incentives

Change customs or immigration policies

Bind national agencies to local economic frameworks.

What local mayors can do instead:

Is it possible to scale the "mayor economy" under the current RA 7160?

It turns out it is.

Local government units can support or initiate proposals for special economic zones by:

Passing a resolution requesting the creation of a freeport or economic zone in their area,

Partnering with the Philippine Economic Zone Authority (PEZA) or other government agencies for zone development,

Working with national legislators (Senators and members of the House of Reresentatives) to sponsor a law for a zone in their locality,

Creating local investment promotion offices (LIPOs) to attract business while staying within existing legal bounds.

Examples

Clark Freeport Zone: Created by national law and managed by the Clark Development Corporation, under the Bases Conversion Development Authority (BCDA).

Local governmemnt units (LGUs) like Angeles City benefit from it, though they did not create it independently.

While only the national government can legally establish a freeport zone, LGUs can play a key role in initiating and supporting such developments.

How to scale the mayor economy

Is 'mayor economy' possible under current rules?

To truly unleash this competitive local governance model, national policymakers should:

Loosen central control: Give LGUs greater fiscal autonomy and flexibility to innovate. That may entail some tweaks in the Local Government (RA 7160, first passed in 1991).

Create rankings and incentives – Publicly rank LGUs on performance metrics like ease of doing business, sustainability, and transparency. (How fast can you get a building permit or business permit in your town/city?)

Reward success, replicate best practices – Cities that demonstrate impact should receive additional funding and scale-ready support. (i.e. offer financing to ramp manufacturing of products with export potential).

Invest in mayoral capacity – Provide training, tech infrastructure, and access to data for local leaders, with links to relevant agency. (How long does one agency sit on a permit application, i.e. for zoning, earthworks, excavation? How to speed up the process?)

Encourage public-private partnerships (PPP) – Mayors should be empowered to collaborate with the private sector, without excessive red tape. (i.e. how can local governments improve water, sewage, flood control, and integrate locally produced renewable energy from solar/hydro/wind/batteries into the power distribution network or electric cooperative?)

From fragmentation to friendly rivalry

Framers of the 1987 Philippine Constitution established a unitary presidential, democratic republic with separation of powers among three branches: the executive, legislative, and judicial.

The president, as both head of state and head of government, leads the executive branch, the legislative power is vested in a bicameral Congress (24-member Senate and the House of Representatives, with 316 seats) while judicial power is vested upon the Supreme Court and lower courts.

However, the current Manila-centric governance and a fragmented, under-invested, under-resourced LGUs create a vicious cycle.

On the Bangsamoro economic policy making

On a positive note, the Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL, ratified in the 2019 plebiscite) grants the regional government the authority to create economic zones, industrial estates, and freeports within the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM).

This authority mirrors the powers of the Philippine Economic Zone Authority (PEZA), allowing BEZA to operate, administer, manage, and develop these zones.

For the rest of the Philippines it is illegal to do the same, unless approved by Manila.

This is problematic, for a number of reasons:

The country is huge: The Philippines’ geography makes centralised governance from Manila increasingly impractical.

Luzon’s mainland alone spans 109,965 km² — almost three times larger than the Netherlands.

Down south, Mindanao covers 97,530 km², roughly equivalent to three Belgiums. Even “smaller” islands like Masbate (3,268 km²) dwarf entire countries like Singapore (736 km²).

Yet despite this vastness, national policies are often crafted with little consideration for regional realities.

Running such a fragmented and diverse archipelago from Manila is like managing a mini-Eurozone west of the Pacific where only Brussels sets the rules — unwieldy and often tone-deaf.

A one-size-fits-all approach to 7,641 islands ignores deep disparities in geography, infrastructure, and resources.

Studies by the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank have both highlighted how centralised governance in the Philippines hampers inclusive growth and local innovation.

To unlock the country's full potential, stronger regional autonomy and genuine decentralisation must move from policy rhetoric to political reality.

This has been proven by the economic necessity, and aptness, of crafting the BOL, which created the BARMM, a mini-state within the bigger Philippine state.

The lack of vibrancy in the regions and economic competition, confines remote regions to a posture of mendicancy towards Manila, and only creates more of the same, including the the worst-in-the-world in the capital. People gravitate towards where jobs are.

One example of neglect: The touristic province of Sorsogon (which boasts natural hot and cold springs, white sand beachers, rich fishing and pastoral grounds), and 3x the land area of Singapore, has no operatonal civil airport.

'Coopetition'

With timely support from the current crop of policy makers, a “coopetition” culture can emerge.

Mayors who outperform should inspire others to follow, and a race to excellence, not mediocrity, could redefine Philippine local governance.

In short, let cities rise. Let mayors lead. And let Filipino innovation flow from the grassroots up.

The next wave of Philippine development may not start in Malacañang — but in the Sangguniang Bayan or Lungsod (City) halls.

Philippines' Top 10 Richest Cities, Provinces and Towns

Quezon City: ₱443.406 billion

Makati: ₱239.478 billion

Manila: ₱77.506 billion

Pasig City: ₱52.152 billion

Taguig: ₱40.840 billion

Mandaue: ₱34.231 billion

Cebu City: ₱30.545 billion

Mandaluyong ₱32.550 billion

Davao City: ₱29.701 billion

Paranaque: ₱27.376 billion

10 Richest Provinces

Cebu: ₱235.738 billion

Rizal: ₱35.594 billion

Batangas: ₱31.999 billion

Davao de Oro: ₱23.107 billion

Ilocos Sur: ₱21.562 billion

Bukidnon: ₱21.058 billion

Iloilo: ₱19.977 billion

Negros Occidental: ₱19.419 billion

Cavite ₱19.342 billion

Pampanga ₱19.127 billion

10 Richest Municipalities/Towns

Carmona, Cavite - ₱6.522 billion

Limay, Bataan - ₱5.791 billion

Silang, Cavite - ₱4.454 billion

Caluya, Antique - ₱3.822 billion

Cabugao, Ilocos Sur - ₱3.805 billion

Cainta, Rizal - ₱3.766 billion

Taytay, Rizal - ₱3.670 billion

Binangonan, Rizal - ₱3.489 billion

Sta. Maria, Ilocos Sur - ₱3.267 billion

Sta. Cruz, Ilocos Sur - ₱3.215 billion

Source: Commission on Audit (2022 data)

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox