Koi story: priceless Japanese fish make a splash

Fish have for decades been popular in Japan, where top breeders take their most prized specimens to highly competitive ‘beauty parades’

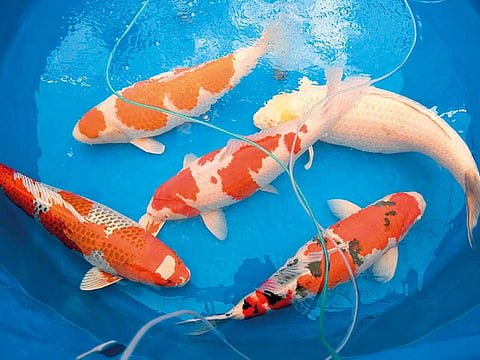

Kazo (Japan): Hand-reared for their colour and beauty, koi carp have become an iconic symbol of Japan that can sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars and even participate in fishy beauty contests.

The nation’s koi carp were brought to the world’s attention when visiting US President Donald Trump was snapped unceremoniously dumping the last of a box of feed into a palace pond in Tokyo.

But the fish have for decades been popular in Japan, where top breeders take their most prized specimens (known as “nishikigoi”) to highly competitive “beauty parades.”

Koi carp displayed in plastic bags during a “nishikigoi (coloured carp) contest” in Tokyo. AFP

At one such competition in Tokyo, judges in sharp suits, notebooks in hand, stride around tanks lined up along a pedestrian street where the valuable koi strut their stuff.

They come in all the colours of the rainbow: pearly white, bright red, cloudy-grey, dark blue, gleaming golden yellow.

But it is the curvature of the fish that accounts for 60 per cent of the final score, explained competition organiser Isamu Hattori, who runs Japan’s main association for breeders of koi carp.

Breeders Ryuichiro Kurihara and Yasuyuki Tanaka transferring a customer’s nishikigoi koi carp to a water tank on their truck in Kuki, Saitama prefecture. AFP

Colour and contrast make up another 30 per cent, he told AFP.

And the final 10 per cent? “Hinkaku” — a concept that is tricky to define and even harder to judge, best translated as the “presence” or “aura” of the fish.

‘Everything matters’

“‘Hinkaku’. It’s either there in the genes at birth, or it’s not,” mused Mikinori Kurikara, a koi breeder in Saitama, north of Tokyo, who says he can spot it in fish when they reach eight or nine months old.

“Put it this way, it’s like looking after your own children every day. You care for your kids and want them to grow healthy. In the same way, you take care of these fish, appreciate them and adore them,” he told AFP.

A less glorious fate awaits the other koi who have not been fortunate enough to catch the eye of the breeder: they are sold off as feed for tropical fish. AFP

At his farm, thousands of tiny “nishikigoi” (coloured carp) dart around deep basins of carefully purified water, meticulously divided by age and colour.

A less glorious fate awaits the other koi who have not been fortunate enough to catch the eye of the breeder: they are sold off as feed for tropical fish.

“It’s a really delicate job, really difficult. Everything matters: the ground, the water quality, the food,” explained the 48-year-old, who took over the farm from his father and is training his son, half his age, in the subtle arts of koi breeding.

Put it this way, it’s like looking after your own children every day. You care for your kids and want them to grow healthy. In the same way, you take care of these fish, appreciate them and adore them.”

“We have many secrets,” he adds mischievously. “But even if we let them slip, it wouldn’t work. You have to be able to feel it.”

‘Social ladder’

These days, any self-respecting traditional Japanese garden has plenty of colourful koi gracing its ponds, but it is a relatively recent tradition.

Around 200 years ago, villagers in the mountainous region around Niigata (in the north-west of Japan) started to practise genetic engineering without knowing what they were doing.

For the first time, they began to cross-breed rare colourful carp, not for food but for pure aesthetic value.

The craze for nishikigoi gradually took over the whole of Japan and then spread into other parts of Asia.

They are especially popular in China, where carp swimming against the tide symbolises the idea of perseverance leading to riches — rather like people climbing the social ladder, said Yutaka Suga, professor at the Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia at Tokyo University.

Today, koi is big business and Japanese exports are booming — 90 per cent of domestic production is exported and sold at auction.

In 2016, Japan exported a record 295 tonnes of koi carp, generating turnover of 3.5 billion yen (Dh114 million or $31 million), an increase of almost 50 per cent from 2007, according to Japan’s agriculture ministry.

As for individual carp, “the prices have become insane,” said carp association boss Hattori.

“Today, a two-year-old carp can sell for 30 million yen each ($265,000) whereas 10 years ago, two million yen was already a very good price,” he told AFP.

Like racehorse owners, many foreign owners leave their prized possessions in their home Japanese farms so they can compete in the most prestigious fishy pageants, which are only open to domestic rearers.

One such owner, Chinese koi collector Yuan Jiandong, was in Tokyo to cheer on some of his own carp.

“It’s not a way of making money. It’s a way of spending it for fun,” laughed the pharmaceutical boss from Shanghai.

But owning koi is so much more than a vulgar display of wealth, he said.

“When you see these beautiful fish gliding around in your pond, you forget the stresses of daily life and you find peace of mind.”

And you can’t put a price on that.