Fighting poverty and hunger

As UNMC chief he is devoted to eradicating illiteracy and promoting equality

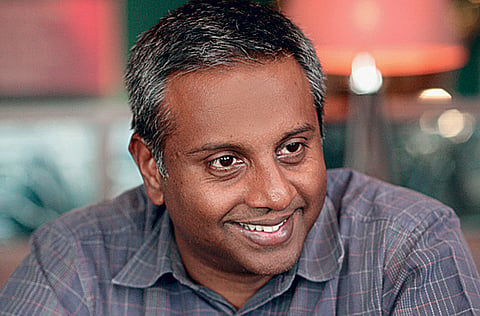

New Delhi: Salil Shetty, Director of the United Nations Millennium Campaign (UNMC) has recently been appointed Secretary General at Amnesty International, the global human rights body. He will assume the new position in June this year.

Having worked as the chief executive of international anti-poverty NGO ActionAid, Shetty joined the UNMC in 2003, shortly after it was set up by then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan.

A successful global campaigning force, UNMC supports citizens in their efforts to hold the governments accountable for the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in over 50 countries.

The objectives include eradicating poverty and hunger, promoting gender equality, fighting against disease and illiteracy and forming a global partnership for development.

In an exclusive interview, the first after his new appointment, New York-based Salil Shetty spoke to Gulf News on issues ranging from global food crisis and greenhouse gas emissions to corruption and governance.

GULF NEWS: As director of the United Nations Millennium Campaign for the last 6 years, how far have you been able to achieve the goals you set out for yourself?

SALIL SHETTY: I am pleasantly surprised on how much progress the world has made on the MDGs. Signed in September 2000 at the UN by 189 countries at the largest gathering of world leaders in history, these goals have become the global framework to plan and measure progress in its objectives.

Part of the progress, in its first 10 years (from 2000 to 2010), can be accounted for by the fact that barring the last year, the developing world in particular has seen a period of very steady economic growth. But having a clear set of benchmarks and targets to be achieved on a time-bound basis has created significant peer pressure and impetus.

The UNMC has played a small but significant role in making this happen. It has supported citizens groups to hold their own governments to account at the local and national level, on meeting their MDG commitments.

Regarding MDGs, in which spheres do you feel frustrated and are unable to operate at your will?

I find it very disconcerting when some of the poorest countries in the world are on track to achieving several of the MDGs, while their more prosperous neighbours do not make enough efforts. This simply reinforces the Millennium Campaign's main message that the core ingredient in the fight against poverty is indeed political will at the highest levels.

Can you cite success stories wherein you have been able to convince countries/governments on seeing your point of view as far as rights and dignity of people are concerned?

At the national level alone, one can focus and list several success stories. We are often told that sub-Saharan Africa is lagging behind on achieving the MDGs. But many of the poorest countries in that continent have shown amazing progress on many of the goals. For instance, Malawi on agriculture, Tanzania on child mortality, Uganda on Aids, Ghana on poverty, Kenya on education and Rwanda and Mozambique on several other goals.

In Asia, we have many star performers including China, Vietnam and Bangladesh. Brazil has tackled the food problem head on with massive cash transfers, resulting in a big decrease not only in hunger but also inequality. This is the result of the collective effort of different stakeholders. At the heart of it, of course, are the poor people themselves in these countries, who have been at the vanguard of this revolution.

The governments have of course played a pivotal role. External support from donors has also helped in many cases. Citizens groups, supported by the Millennium Campaign, have played their part as in case of the ‘Make Poverty History' campaigns in many developed countries across the world. These include the United Kongdom, Australia and Canada playing a crucial role in increasing aid levels and cancelling debts.

What have been your most cherished moments in the last decade?

It's not easy to answer that. But yes, the most satisfying moments have been when I've met somebody whose life has been positively impacted through the efforts that I've been involved with. In my previous role in ActionAid, it was easier to identify instances, as we worked a lot at the very micro level. But with the UN, my work is more focused on trying to bring about changes in the bigger picture and the Millennium Campaign has been able to foster a fair bit of change in this regard. The ‘Stand Up and Take Action' campaign that mobilized over 173 million citizens was certainly a high point, not just because of the scale, but also of the quality of actions and the steady growth in participation, year on year.

Regarding ‘global food crisis', would you rate India at par with some African countries? Or is the situation a lot better in India?

It's hard to generalise things at a continental level and compare India and Africa in a superficial manner. As mentioned earlier, Malawi, one of the poorest countries, has moved from being a ‘basket case' to a ‘show case' on agricultural production in a matter of few years. In fact, it is now a net exporter of food to many of its neighbours. India, on the other hand, faces the stark reality of 40 per cent of its children facing malnutrition, farmer suicides and annual reports of starvation deaths in places like Koraput and Kalahandi in Orissa.

At the same time, it is true that in comparison to many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the government in India has a stronger capability and systems of food stocking and distribution. India doesn't face transitionary food insecurity at a large scale. But the problem of chronic hunger continues to haunt a worryingly large proportion of India's population.

In the Indian context, do you feel the leadership here takes development issues seriously and allocates resources accordingly?

The United Progressive Alliance and more recently the Congress-led governments at the Centre have come to power on an anti-poverty and inclusion platform. In that sense, the leadership at the national level takes the MDGs very seriously. There has been a significant increase in budgetary outlays for the realisation of the MDGs on livelihood, education and health.

However, in many sectors the per capita investment is still very low. In the health sector, at less than 3 per cent Gross National Income, India's public investments in health is amongst the lowest among poor countries.

But apart from the need to allocate greater resources, the biggest problems in India are essentially at the local implementation level, which pose the greatest bottlenecks. Even a much smaller and poorer neighbour like Nepal, which has been mired in conflict for the last decade, has done better on many of the goals.

Highlights of a campaigning career

- Salil Shetty was born to Hemlatha Shetty and V.T. Rajshekar on February 3, 1961 in Mumbai

- Graduated with an Advanced Accountancy BCom from St. Joseph's College of Commerce, Bangalore - 1981

- Proceeded to the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad and got his MBA - 1983

- Began his career with Wipro in Mumbai - 1983

- MSc in Social Policy and Planning from The London School of Economics - 1991

- Chief Executive, ActionAid worldwide, 1998 - 2003

- Director, United Nations Millennium Campaign, 2003 - to date.

- Scheduled to take over as Secretary General, Amnesty International - June 2010