He is a free man because his victim's sisters said he should be released from prison

Criminal justice experts see a shift in the debate over mass incarceration

On Thursday, Angelo Robinson walked out of an Ohio prison. Robinson, 43, had spent more than half of his life behind bars and, until quite recently, had no reason to believe he would get out anytime soon.

But a remarkable effort to free him began last year, and eventually both the prosecutor's office that won his 1997 murder conviction and relatives of the woman he killed supported his release.

No one disputed his guilt. His release Thursday was achieved through an unusual legal arrangement based on the simple notion that Robinson had, as one of the victim's sisters put it, "been punished enough."

Some criminal justice experts said the very fact of a release like this, however unique, reflected a shift in the debate over mass incarceration. People who were once left completely out of that conversation - those locked up for violent crimes - are now moving, slowly, toward the center of it.

"I think it points to the fact that the culture has changed around incarceration," said Nicole Porter of the Sentencing Project, a group that advocates improvements to the criminal justice system. "People are willing to do things that people weren't willing to do 10 or 15 years ago."

More than half of inmates in state prisons were convicted of violent crimes. This is chiefly because of sentencing; while the rate of violent crime has declined substantially over the past two decades, the average time served for a murder conviction has more than doubled, and life sentences have proliferated.

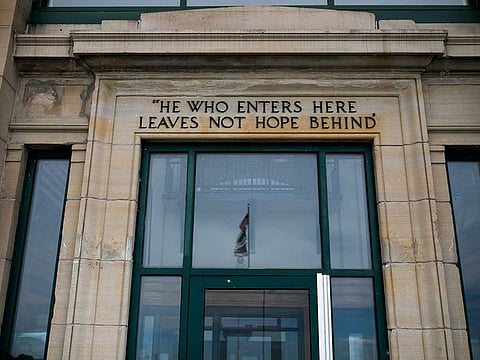

Beyond Guilt

Yet many national discussions about the prison system, including some exchanges in Wednesday night's Democratic presidential debate, have focused only on nonviolent offenders.

Criminal justice advocates argue that substantially reducing incarceration rates in the United States would be impossible without releasing some people who committed violent crimes. And, anticipating political resistance, they point to evidence that violent offenders have lower rates of recidivism than others.

This year, the Ohio Justice and Policy Center, based in Cincinnati, began an initiative called Beyond Guilt to push for the release of people who have spent a long time behind bars but shown evidence of rehabilitation. Robinson's case was already in the works.

The story started in 1997

In 1997, Robinson was dealing drugs in a Cincinnati apartment when men in ski masks showed up, firing shots and trying to force their way in. Robinson, who was in a back bedroom, heard someone at the bedroom door and fired several shots. It turned out to be Veronica Jackson, an acquaintance of his and a 34-year-old mother of six.

He was offered a deal at the time to plead guilty to manslaughter but chose to go to trial. He was convicted of murder and sentenced to life.

Last year, David Singleton, the center's director, who had met Robinson in prison years earlier, began to think about how to get him out. There was no program in Ohio that allowed an early release for someone like Robinson. Singleton began talks with the local prosecutor's office, which did not oppose the idea and even suggested potential ways forward.

"The defendant served 23 years in prison for murder and possession of cocaine and our hope is that he takes full advantage of his second chance," said Julie Wilson, a spokeswoman for the Hamilton County Prosecutor's Office.

They arrived at a mechanism for his release: The judge agreed to vacate Robinson's murder conviction and accepted a guilty plea to lesser charges of involuntary manslaughter and cocaine possession. He then sentenced Robinson to time served and put him on probation. In his reasoning, the judge specifically cited the consent of Veronica Jackson's family.

Some of her relatives, including at least one of Jackson's sons, steadfastly opposed the plan to release Robinson. Others, though initially resistant, changed their thinking. A brother, currently in prison himself, was in favor. Two of the Jackson sisters submitted affidavits in support of Robinson, and one said she was looking forward to meeting him.

"I'm so glad to hear that good news," said Sarah Jackson, 57, who said she had been especially close to her little sister Veronica. "I want to talk to him and let him know that he is forgiven and that he's going to get his life straightened out now."