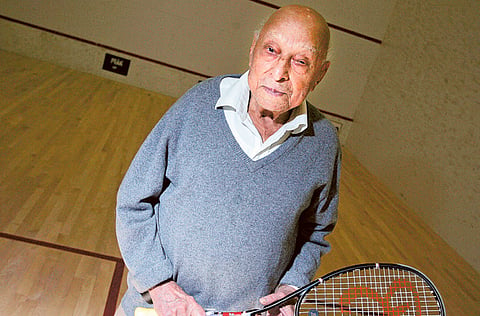

Pakistani squash great Hashim Khan in poor health

His family basks in memories of 100-year-old legend despite his condition

Aurora, Colorado: Hashim Khan’s family really has no idea how old their father is since he never had a birth certificate.

Best guess? He turned 100 on July 1 — that’s what they celebrated anyway. He also could be older, some say even as old as 104.

Just another intriguing layer to the lore of Khan, one of the greatest squash players ever.

He’s the patriarch who got the ball rolling on Pakistan’s squash supremacy, winning his first British Open title in 1951 at an age when most retire, and then six more championships after that. He later travelled to America to raise a family of 12 and help hook a younger generation on the sport.

Over the last six months, his health has drastically deteriorated. Hospice workers are providing around-the-clock care for him at his home. His family remains by his side, reminiscing about his squash heyday.

The tales they tell: Like how he started out playing squash barefoot. Or how he once went through a player’s legs to get to a ball near the front wall.

Or how they heard Buckingham Palace built a squash court just to watch their father’s flair.

“Just a rumour,” said Gulmast, one of Khan’s seven sons, who all played on the professional level.

“I like the concept that his age is shrouded somewhat in mystery,” his son, Sam, said. “He’s a whirlwind who comes out of the distant Himalayan mountains and conquers the world. Nobody knows where he came from or even when he came from. It’s sort of fitting that it would be that way.”

Around his house, Hashim Khan doesn’t have many traces of the trinkets he acquired throughout the decades. There’s a framed picture of him shaking hands with Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh. And on a table by the couch, an encased picture of him on the cover of Squash Magazine. Another of him posing with a racket.

His awards are displayed inside the Hashim Khan Trophy Room, which is a squash court the members at the Denver Athletic Club converted into a shrine to him.

Three of his friends stopped by on Thursday, just to pay their respects. When they started talking squash, his eyes lit up.

“Remember your rules for squash? Snap your wrist, don’t hit the tin ... fight like a tiger,” said Marshall Wallach, who started a foundation in Khan’s honour.

Another friend, Dennis Driscoll, asked Khan to demonstrate his grip — the one that was so accurate and oh so powerful.

Khan bent his wrist ever so slightly, as if he held a racket in his hand again. As if he was that player he once was decades ago.

He was exposed to squash through his father, Abdullah, a chief steward at a British officers’ club in Peshawar. Back then, the youngster would go to the outdoor courts to watch the officers play and fetch their errant shots.

Eventually, the officers would head inside to escape the baking sun. That’s when Khan sauntered onto the court and emulated their shots wearing no shoes, holding a cracked racket, and using a broken ball.

Khan’s father died in a car accident when he was 11, and he dropped out of school to become a full-time ballboy. He honed his skills playing the officers. He later became one of the club’s coaches.

At 37 — and at the behest of the Pakistan government eager for a national hero — Khan went to the British Open, the unofficial world championship. He beat the best player in the world, four-time defending champion Mahmoud Al Karim of Egypt, 9-5, 9-0, 9-0, for his first title. His last was at 44.

About then, he taught his brother, Azam, to play squash, and he won four titles. Hashim Khan’s cousin, Roshan Khan, and nephew, Mohibullah Khan, each captured one. Add Khan’s cousin’s son, Jahangir Khan, who won 10 straight titles through the 1980s, and the “Khan Dynasty” accounted for 23 British Open titles.

Khan brought his family to the US in the early 1960s after being offered a lucrative deal to teach squash at the Uptown Athletic Club in Detroit. He later took a pro position at the Denver Athletic Club in the early ‘70s, with membership instantly soaring.

The past few years have been difficult for Khan, who lost his daughter in 2007 and then his wife of 65 years, both to diabetes.

Up until recently, he could usually be found at the club. Not playing, of course, he gave the game up at 93, but watching from the stands and offering tips.

More than winning, Khan was known for sportsmanship — always allowing an opponent to leave the court first. He was all about respect.

That’s why his youngest son, Mo, has received so many calls and emails from well-wishers. Even Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper recently stopped by for a visit, Mo said.

“We never really thought of him as this world-class champion and one of greatest players in history,” Sam Khan said. “To us, he was just dad.

“He just loved the game.”