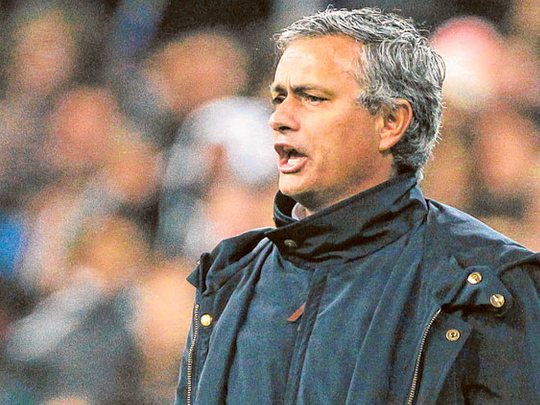

London: Barring any unforeseen twists in the tale, Jose Mario dos Santos Mourinho Felix will soon return to his adoring British public with a second stint as manager of Chelsea.

While the return of the “Special One” will largely be a matter for celebration in south-west London, there’s also a huge and ready constituency nationwide, licking their lips in anticipation of more fun from this much-loved pantomime villain, currently serving his last days at Real Madrid.

On Friday night, Mourinho described this season as the “worst” of his career, following a 2-1 Kings Cup final defeat to city rivals Atletico. This came at the end of a season in which he had been feuding, it seems, with almost all of the Real squad, and kept Iker Casillas, the Spanish goalkeeper — chief feudee — on the bench for much of the time.

For most of us, our first Mourinho Moment came in March 2004, when his Porto team scored a last-minute goal at Old Trafford to send Manchester United crashing out of the Champions League. Dramatic as Costinha’s winner was, it paled next to the unbridled celebrations of his manager. Mourinho ran the length of the touchline before sliding to his knees — to scowls of disdain from Alex Ferguson — and pumping his fist at the shell-shocked crowd. It was to be the first salvo in a decade of lively encounters between the two.

Jose Mourinho was born 50 years ago in the port city of Setubal, 30 miles south of Lisbon. Football was in his blood. His father, Felix, was capped by Portugal and Mourinho played to a middling level at Belenenses and Rio Ave. Yet it was coaching that caught his imagination. He started out on a familiar route into football management, coaching Vitoria’s youth team in Setubal.

The 1992 arrival of Bobby Robson as manager of Sporting Lisbon was, by common consent, the game-changer for Mourinho. Starting out as his translator, he quickly earned Robson’s respect for the intense detail of his preparatory notes. When Robson left for Porto, then Barcelona, he took his trusted match analyst with him, a journey that ended with promotion, when Mourinho took over as Porto coach in 2002. On arrival, he wrote a letter of welcome — a mission statement — to every member of his squad. It began: “From here on in, each practice, each game, each minute of your social life must centre on the aim of being champions.”

In his first season, Porto won the Portuguese league and the Uefa Cup, winning the league again the following year — and then came that memorable 2004 Champions League run. After dispatching Manchester United, Porto went on to win the competition outright, an achievement that brought Mourinho to the attention of Roman Abramovich.

If we’d thought his Old Trafford celebration was entertaining, it was as nothing compared to his first interview in the Chelsea hot seat. He said he would expect the sack if he were to fail, but for Mourinho, failure was inconceivable. Why? Because he was special. “Please don’t call me arrogant. I’m European champion and I think I’m a special one.” Mourinho had spoken. The Special One was born.

Mourinho is supremely skilled at manipulating the media and enraging the opposition — players, supporters and managers alike. With one well-timed soundbite, he would set the cat among the pigeons. Coming to Chelsea the summer after Arsenal had gone a whole season unbeaten, Mourinho said: “Look at the way your teams play against Arsenal. They don’t believe they can win.”

The emphasis on “your” and “they” was genius, implying that he, an outsider, was about to show the Premier League how it should be done. It worked a treat. The usually phlegmatic Arsene Wenger allowed himself to be drawn into a slanging match, commenting on any and every Chelsea slip-up. This apparent obsession led Mourinho to label him a “voyeur”.

There’s a school of thought that this bullish, antagonistic persona is just that — a mask, a smokescreen, carefully cultivated to take the pressure away from his players so they can fully focus on the task in hand. In doing so, he creates a siege mentality that is predicated on loyalty. There’s a counter-argument that Mourinho craves the limelight and is addicted to praise, describing all his teams and their achievements as Me, My and Mine.

What’s for sure is that he’s a Machiavellian operator who picks his spats as adroitly as he picks his teams. Having incensed Alex Ferguson in 2004, Mourinho was quick to realise it had been a Pyrrhic victory. He began to court Ferguson, buttering him up with praise and playing to his self-image as a man of superior taste.

Mourinho was solicitous in his praise of Manchester United, their “legend” and, particularly, Ferguson. He as good as treated this year’s Champions League match between the clubs as an open audition, praising his venerable opponent. Madrid won and Mourinho was well aware that Ferguson himself would have a huge say in the anointment of his successor.

There’s something irresistible in the notion that the wily Ferguson was on to Mourinho all along. He was all too aware that the faithful dad and husband was a serial adulterer when it came to football clubs. That the same devout family man who raised £25,000 (Dh139,000) for Tsunami Relief and donated his Uefa Ballon D’Or to the Bobby Robson Trust in 2011 is also the man who poked Barcelona coach Tito Vilanova in the eye then ran away; who boasted of his €15 million (Dh70 million) salary to the Italian media; who is regularly censured and sent to the stands for his outbursts; and who sprinted down the Old Trafford touchline, pumping his fist at the crowd.

Mourinho is all these things and more. He would guarantee great copy, give great headline, ruffle a few feathers, then go home to the wife and kids. Welcome back. We’ve been expecting you.