Highlights

- Here's how the Philippines can leap-frog the "nickel boom".

Manila: Filipino business tycoon Manuel V. Pangilinan, a.k.a. MVP, has revealed his electric dreams. His vision: take advantage of brisk global electric vehicle (EV) demand. How? By scaling up mining.

Specifically, Pangilinan, 77, who is at the helm of the listed Philippine gold-copper miner Philex Mining Corp – is targeting nickel.

MVP, the Wharton-educated CEO of telecom carrier PLDT and Smart, who also chairs power distribution giant Meralco, has made known his bold plans to enable his country to take part in the so-called “nickel boom”, a strategy that has worked remarkably well for Indonesia.

Why nickel?

Nickel, a silvery-white lustrous metal, is everywhere you look. Check your phone. It’s a “hidden” mineral, used in making stainless steel found in most digital devices as well as in medical equipment.

Increasingly, it has become a vital mineral for the lithium-ion batteries used in EVs.

The Philippines, a highly mineralised country, has at least 34 operating nickel mines. It is the world’s second-biggest nickel producer. Yet the country contents itself with exporting mostly raw nickel ore, instead of products manufactured from its mineral wealth.

MVP wants to expand nickel mines: “It's the mines that should be expanded to the point where you have the basis to justify smelting or refining operations in this country,” Pangilinan was quoted as saying.

For decades, mining has suffered from severe under-investment. For example, the Mines and Geosciences Bureau has identified 9 million hectares as having high mineral potential: less than 3% is currently covered by mining tenements.

In 2023, the country produced an equivalent of 400,000 metric tons of nickel ore. It was much higher in the past, having peaked in 2015 at 554,000 metric tonnes, briefly overtaking Indonesia, today’s top producer.

Still, the Philippines accounts for anywhere from 10 to 12 per cent of the in-demand metal globally, after top producer Indonesia, which accounted for 1.8 million metric tons in 2023.

Until now, the Philippines exports a lion’s share of its nickel ore to China. Notably, the Philippines even exports nickel ore to smelters in Indonesia, according to the 2023 Reuters report. It also exports some semi-processed nickel to Japan, via Sumitomo Metal, which then supplies them to Panasonic, Tesla’s main battery supplier.

For some reason, the Philippines has completely ignored the US, where EV sales hit 1.2 million in 2023, a 58 per cent jump.

Nickel ore vs refined nickel

Nckel is a key mineral. It is highly ductile and has excellent resistance to corrosion and oxidation, making it 100 per cent recyclable. It is used in the “cathode”, which has a direct influence on the energy density of a battery cell.

These attributes are vital for various applications, including infrastructure construction, chemical manufacturing, telecommunications, energy provision, environmental conservation, and food processing.

Other alloys of nickel can be used in boat propeller shafts and turbine blades. But it’s the commodity’s use in batteries as a cathode material that pushed demand for nickel to skyrocket.

The more nickel, the more battery power. This is measured in terms of energy density: "volumetric” energy density is the amount of energy stored in a given unit volume; “gravimetric” energy density is energy per mass (measured in watts per kg).

On Tuesday (February 20, 2024), the live price of refined (99.8 per cent) nickel is $15,973.97, according to Markets Insider data.

Global nickel production hit 3.06 million tonnes in 2022, and grew further to 3.372 million tonnes in 2023, according to the Nickel Institute. Between 2023 to 2030, nickel production is expected to grow at an average annual compounded rate of 5 per cent.

Of the 3+ million metric tonnes of new or primary nickel produced and consumed each year, this is evenly divided between Class 1 (containing a minimum of 99.8 percent nickel) and Class 2 (containing less than 99.8 percent nickel) units, according to the Nickel Institute.

Class 1 nickel is primarily used for battery cathodes. Class 1 nickel is usually sourced from Russia, Canada, and Australia, while Class 2 nickel is primarily sourced from Indonesia, the Philippines, and New Caledonia.

Role of nickel in EVs

Elon Musk’s nickel concerns

Given the rise in EV adoption, demand for nickel and other battery minerals is expected to rise even further in the short term. In 2021, Tesla CEO Elon Musk has cited concerns about the inability of its suppliers to deliver enough batteries.

“We are production-limited. The reason we are making our own cells is to *supplement* max production of suppliers. Even moving at full speed, they cannot build enough cells.”

“Nickel is our biggest concern for scaling lithium-ion cell production. That’s why we are shifting standard range cars to an iron cathode. Plenty of iron (and lithium)!”

Following are key reasons why the Philippines is left behind in the so-called “nickel boom”:

#1. Disruptions

Mining is a hot-button issue: Philippine Communist rebels used to routinely raid mining sites. Several such raids were made on nickel mines — three in 2011 and another 2015 — briefly disrupting their operations.

With the military’s relentless anti-insurgency drive, however, alongside rural development projects, the armed communist problem has gone down to its lowest, almost insignificant level. Many war-weary volunteers have either died or had given up their arms altogether after waging the world's longest ongoing communist insurgency, a conflict that so far claimed 43,000 lives.

Nickel is a key EV battery component. It is used in the “cathode”, which has a direct influence on the “energy density” of the battery cell.

If the peace-and-order issue was once an issue, and is now almost a non-issue, why is the Philippines’ nickel production and exports down – while its neighbour Indonesia has experienced a “nickel boom”?

In 2022, exports of nickel from the Philippines actually declined by 9.36 per cent over 2021, according to industry data.

Besides the supply-and-demand equation, there’s the matter of legislation. The country’s largest business group, the Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industry (PCCI), described local mining laws as being "too restrictive". For the mining sector, it means most investors hold back or go elsewhere, thus dulling the industry's potential to be a major economic contributor.

In 2023, George Barcelon, PCCI president, told local media that the government was imposing numerous taxes on commercial mining firms as well as environmental regulations that discourage.

“The fact is, when our laws are too strict, the legitimate miners tend to be more careful because it’s a big investment,” Barcelon said at a forum. He said the small miners generally flout the rules and are the ones who create a lot of issues and pollution.

Barcelon also argued that more mining should be allowed due to modern-day technology being available to ensure it is not harming the environment.

“We were afraid of mining before that they may be spilling their refuse irresponsibly. You can monitor them with drones, 24-7,” he said.

#2. High power rates, poor infrastructure

Another major reason, as cited by New York-based investment banker Stephen Cuunjieng, is high power rates.

Filipinos pay among the highest electricity prices in Southeast Asia, along with Singapore.

In December 2021, the Philippines' residential rate was $0.16/kWh, second to Singapore ($0.18/kWh) and higher than Thailand ($0.10/kWh), Indonesia ($0.10/kWh), and Malaysia ($0.05/kWh), according to an Ateneo de Manila University study.

The Philippines is heavily dependent on imported fuel, and has also completely ignored nuclear power.

Generation charges (fees paid by distribution utilities to power suppliers) account for around 55 per cent of consumers’ electricity bills, said Jephraim Manansala, chief data scientist of the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities (ICSC).

The net result: investors ignore the Philippines in favour of cheap-power neighbours – as the electricity typically accounts for about 30 per cent of the cost of input.

And unlike its neighbours, Philippine policy makers and legislators remain iffy about any decision to subsidise electricity. There's been much talk about nuclear power, but it hasn't produced a single kilowatt of electricity.

The country also falls behind in several crucial indicators including power and road infrastructure. To be fair, renewable energy and the communications infrastructure have greatly improved, and continues to improve, thanks to updated laws allowing greater competition in these sectors.

#3. Lack of whole-of-nation 'nickel boom' strategy

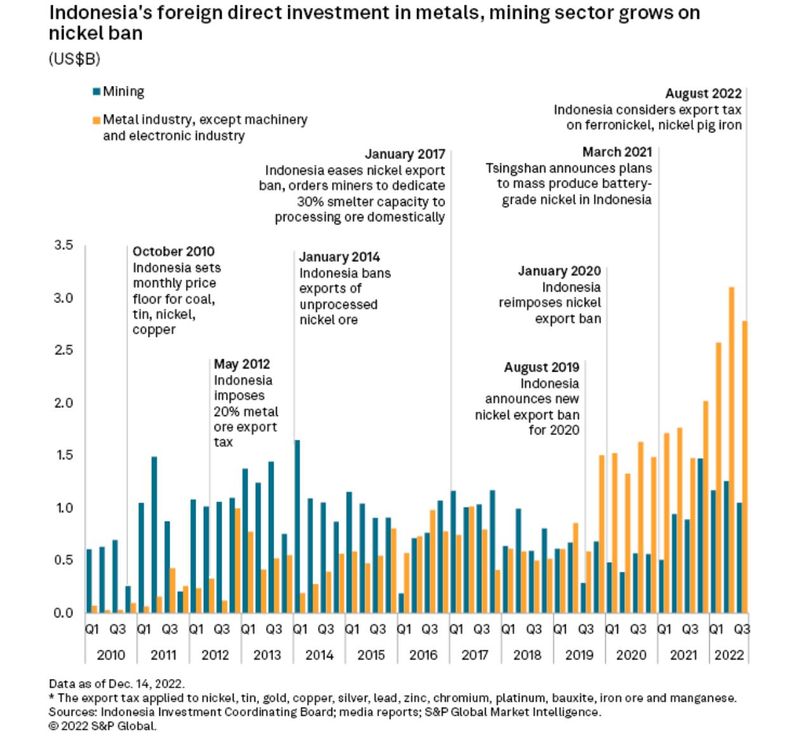

This is the biggest challenge yet. And in this, the experience of Indonesia is a good example. In 2014, the Jakarta government under Joko “Jokowi” Widodo shocked the nickel market when it made good on a commitment to ban all exports of unprocessed minerals.

Following the move, nickel jumped above $17,000 per metric tonne in the global market. The price spike was short-lived. By August 2016, nickel went down to $10,755 a tonne in London Metals Exchange.

Due to insatiable demand, however, the average nickel import price amounted to $31,176 per tonne in May 2023. It has since gone back down, hovering between $21,000 in Q3 and $22,000 in Q4 as the global growth outlook improves, according to ING.

Indonesia doubled down on its ban on unprocessed minerals in 2020. The move was deliberate: For one, it forced miners to process the ore domestically, thereby adding more manufacturing jobs – and creating more value for Indonesia’s nickel production.

The ban worked. Not only did it generate a $14-billion fresh investments in local nickel smelting capacity; it also saw double-digit growth for its nickel downstreaming provinces (Maluku Utara and Sulawesi Tengah) and a 10-fold increase in the value of nickel exports — from $600 million in 2016 to $6 billion in 2022, according to Trading Economics.

Foreign investments have already developed an integrated steel industry. Indonesia is now on track to repeat this success up the EV battery supply chain. There’s been talk about Tesla investing in a battery factory in Indonesia, too, though nothing came out of it.

On record, Tesla has mainly sourced its batteries from Japan's Panasonic for many years. This means the Philippines, which supplies Sumitomo, which supplies Panasonic, is one of the main sources of nickel that goes into Teslas.

#4. Red tape, poor infrastructure

Having rich natural resources, and a critical mass of highly trained and educated talent — key considerations for attracting investors — are no match for a tough business climate and convoluted business laws.

The Philippines has an anti-red tape law passed on May 28, 2018, which amended an earlier law (RA Act 9485, the Anti-Red Tape Act of 2007.)

In 2023, the Ease of Doing Business Law was also signed. Still, it takes 28 days and 16 procedures to register a company in the Philippines vs 2.5 days on average in Singapore – in some cases, it takes as little as 15 minutes.

9 m

hectares identified by the Philippine government as having high mineral potential is covered by mining tenements (source: Mines and Geosciences Bureau)In a recent World Bank ease-of-doing-business metric, the Philippines ranked at far No. 95 (out of 190 countries), while its neighbours Singapore ranked No. 2, Malaysia ranked No. 12, and Thailand at No. 21, Vietnam at No. 70 and Indonesia at No. 73.

The Philippines also lags in rail connectivity, road connectivity, traffic congestion and power supply. As far as the digital backbone goes, Vietnam has more than 90,000 cell sites while the Philippines has 17,850. The Philippines spends about 5 per cent of GDP on infrastructure while Vietnam has recently accelerated theirs to 8 per cent.

Bureaucratic processes are due in part to archaic laws, as well cultural and institutional factors: complex and outdated regulations, inefficient government processes, corruption, and a severe lack of automation in administrative procedures.

The Philippines has been working on reforms to cut bureaucracy and improve the ease of doing business. Significant challenges remain.

Boosting investments: how and why

The Philippines has abundant minerals – gold, copper, iron ore, lead, zinc, nickel and chromite (also silver, mercury, molybdenum, cadmium, and manganese) – from major and minor deposits on the islands of Luzon and Mindanao.

As in any industry, attracting more investments, and tech know-how in nickel production, from smelting to refining, is key.

“For Indonesia and the Philippines, we have substantial resources (of nickel),” said Dante Bravo, president of the Philippine Nickel Industry Association.

“But, of course, we have to prepare. We have to invest more in exploration. We have to allow more investments in the industry, make the environment more attractive. That’s oneidea of how we can support demand for the long-term, particularly the demand for nickel in the battery-grade sector.”

Bravo believes the nickel boom is only starting. "We see that there’s going to be a lot of activity in the EV sector," he said, citing estimates that investments in the EV space will hit $1 trillion in 5 years.

As for Indonesia, its “nickel boom” has also boosted local job creation, showing the “multiplier effect” of manufacturing – which means that, on average, the addition of one manufacturing job creates nine others.

Manufacturing also has the highest multiplier effect of any economic sector: for every $1 spent in manufacturing, another $2.74 is added to the economy.

< 3 %

percentage of the 9 million hectares identified by the Philippine government as having high mineral potential is covered by mining tenements (Source: Mines and Geosciences Bureau).Way forward

For the country to take advantage of brisk global EV demand, MVP offers this unsolicited advice: expand the mines.

Currently, less than 3 per cent of the 9 million hectares that have been identified by the Philippine government as having high mineral potential is covered by mining tenements, according to data from the Mines and Geosciences Bureau.

MVP also said he supports the plan to ramp up resource processing locally in order to export higher-value products. Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.'s government has been pushing miners to invest in the downstream sector to become a major player in the EV supply chain.

Manila has also considered following Indonesia's lead: by taxing nickel ore exports among a range of measures to lure investment in manufacturing and processing plants.

TIMELINE

- April 2021: Former President Rodrigo Duterte decided to lift a 2012 moratorium on new mining agreements.

- December 2021: An order overturning a 2017 ban on open-pit mining was issued by then- Environment Secretary Roy Cimatu.

- 2022: Metal production increases almost 32 per cent vs 2021. Total export value for 2020–2022 hit $18.7 billion or 8.51 per cent of the country's total exports.

A nickel a surplus situation is expected this year (2024), creating a downward pressure on price, though demand from the stainless steel industry is also seen to continue tracking upward.

To harness nickel's boom potential, a whole-of-nation, whole-of-industry approach may be needed. With each step, fresh investments are needed. Environmental factors, too, need to be taken into account, if the country wants to be seen as an ethical mineral supplier. For example, open-pit mining, often deemed as the most cost-effective ore extraction method, is also recognised as one of the most environmentally destructive techniques.

For example, in April 2005, mining and processing of gold, silver, copper and zinc started in an open-pit mine on Rapu Rapu island. Due to poor environmental safeguards, it was suspended six months later after two heavy cyanide-laden spills were released into water bodies, causing the ecological death of rivers and fish stocks.

As mines are expanded, recalibrating legislation and environmental rules may be needed to address environment concerns requiring the use of latest technology. More important, a bluepint to boost smelting and manufacturing could potentially allow the country to grab a bigger share of direct foreign investments.

For MVP, these are the key challenges: expertise, technology, and capital to explore, conserve and develop the country’s nickel reserves more efficiently and safely.

Nickel, given it desirable power density-booster qualities, is a critical mineral of the battery EV era. Amid global supply chain disruptions and the higher demand for electrification, there will be an increasing focus on sourcing the commodity from reliable and environmentally-responsible sources.

Riding the wave of the “nickel boom” could just hold the key for the country to hit a higher middle-income nation status sooner than later.