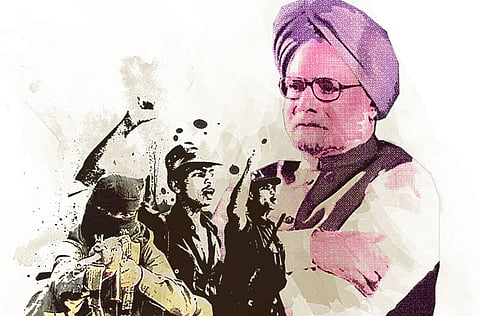

Singh is not coping with India's problems

His government seems incapable of checking corruption and Maoist violence

Maoists kill 40 more people, including security officials, at the same place — Dantewada, in Chattisgarh — where some Gandhians had marched for peace earlier in the week. The transfer of essential supplies to the northeastern state of Manipur continues to be blocked by the Nagas. Food prices have increased by 20 per cent in six months. Teachers assault a vice-chancellor. Two passengers are killed in a melee that the railway officials caused by changing the platforms of two trains just before their departure. A cleric with a beard is detained by police for one day on the complaint of a lady passenger, who suspected him of being a terrorist.

All of these things have happened one after another in a couple of days, giving the impression that the Manmohan Singh government, completing its sixth year of rule this month, is not able to fix the country's problems. No doubt, some of them are trivial, but they underline the fact that there is no accountability. More than that, what they emphasise is the listlessness that has crept into governance. It is not so much the systematic failure but the government's inability to deal with even minor hiccups that grates.

The obvious explanation is that the prime minister, who has been described as an economic ‘guru' by US President Barrack Obama, is out of his depth when dealing with even mundane affairs. His focus on maintaining nine per cent growth has pushed everything else into the background.

Yet his main failure seems to be his inability to tackle the biggest challenge: corruption. It has infected society, pervading every field. Understandably, the prime minister has to take into account political compulsions. He has to overlook the malpractices or sheer dishonesty of coalition partners to stay in power. But did the Congress party have to go to the extent of foregoing prosecution in cut-and-dried cases? Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Mayawati, who has 21 members in the Lok Sabha, has been let off the hook in the disproportionate assets case. Telecommunications Minister A. Raja of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, which commands 18 seats in the Lok Sabha, has cost the exchequer Rs40 billion (Dh3.1 billion) in the 2G bandwidth allocation scandal.

Consequences

I am not making a moral argument. I am drawing attention to the consequences. Corruption is beginning to be accepted as a normal way of life in India, yet I do not recall the prime minister making any recent statement against it.

Had Singh pursued the proposal to appoint a Lok Pal (ombudsman) with the power to look into corruption in high places, he would have been seen as at least creating an investigative institution independent of the pressure that the ruling party in a minority has to reckon with. The Lok Pal, whose creation was part of the Congress election plank, would have reviewed the evidence collected by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). Incidentally, it is a pity that the CBI is a government department. This does not evoke confidence in what it does.

The prime minister has rightly identified the Maoists as the greatest threat to the country. Their violent defiance and the killing sprees in which they indulge are adequate proof of their challenge to the state. But this does not mean that the Indian Constitution can be ignored.

The Union Home Ministry's recent threat to punish individuals who are in contact with the Maoists makes political discussion difficult. The People's Union for Civil Liberties has characterised the statement as "a crude and unsuccessful attempt to curb the fundamental right of speech". The government should not equate criticism with criminal acts. In fact, Congress leader Sonia Gandhi has herself criticised the government for not advancing development in Maoist-infested areas. Yet equating Maoist violence with a lack of economic progress is oversimplifying the problem — that they do not believe in the ballot box is the real issue.

In matters that challenge the country's integrity, the government should seek consensus. All political parties should come together to undermine Maoist propaganda. They claim to speak for the rights of the marginalised, including landless peasants, tribal groups and dalits. But the Maoists have been responsible for serious abuses, including the destruction of schools and hospitals, extortion torture, and killing.

In the fight against the Maoists, it is important to have the cooperation of the states. India is best governed locally, not nationally. The states have to participate, though they are dependent on the centre for weapons and training. But Home Minister P. Chidambaram gives the impression that he is the only person standing between chaos and order in the country.

As for the blockade, Manipur needs New Delhi's support because the state has suffered from the excesses that the security forces have committed there. The Nagas' strength is their well-equipped underground force, an equal irritant to the centre.

Democracy survived in India even when the Congress government suspended fundamental rights some 32 years ago. The Maoists or their ilk cannot extinguish the nation's faith in the ballot box. What is needed is the right approach and the political will.

Kuldip Nayar is a former Indian high commissioner to the United Kingdom and a former Rajya Sabha member.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox