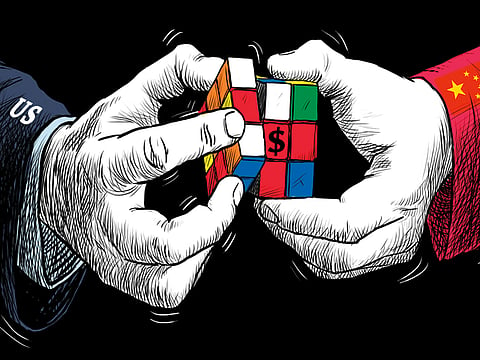

Why US-China trade war is still on the cards

Any increased US veto of foreign investment and mergers could therefore see China — and indeed other countries — respond in a like-minded way

Chinese Finance Minister Liu Kun said last Friday that Beijing would respond “resolutely” after the breakdown of bilateral talks with United States to avoid a potential all-out trade war. While financial markets had been buoyed by hopes of a breakthrough, the inauspicious political backdrop to the session indicated this was very unlikely.

The negotiations, the first since June, coincided with the enactment of $16 billion (Dh58.84 billion) in new US tariffs on Chinese imports. A way out of the trade impasse now looks potentially even further away, and may require the personal intervention of US President Donald Trump and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping when they are next scheduled to meet in November at the G20 and Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation forums.

The bleak political context to the meeting was set by Trump’s signing of legislation last week, requiring the US commerce secretary to deliver a ‘Report on Chinese Investment’ in the US to Congress and the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) every two years, up to 2026. While the bill focuses on military capabilities not just of China, but also Russia and Iran as “potential adversaries”, it singles out Chinese investment as a security threat and zeros in on Beijing’s ‘Made in China 2025’ plan.

The reaction in Beijing has been predictably furious and made success in last week’s negotiations even less likely. The Chinese Defence Ministry asserted that the new law “abounds in Cold War thinking, exaggerates the level of the China-US confrontation ... undermines the atmosphere of development of China-US military ties, damages China-US mutual trust and cooperation”.

What the legislation certainly underlines is how much the Trump administration is focusing on perceived national security risks around inward and outward investments. Since 1990, there have been only five cases where US presidents have blocked big commercial mergers involving US firms: Two of these have been under Trump, including his order in March blocking Broadcom from merging with US-based Qualcomm.

For Trump, there is a clear political narrative around his actions in this area that he sees as a key plank of his ‘Make America Great Again’ agenda. This programme includes reducing the US global trade deficit and cracking down on trade practices perceived to be unfair. Especially with the new law, the president is only likely to become more activist in this area — at least as long as he perceives there is a political benefit to doing so, and key foreign countries resist his calls for trade renegotiations.

The new legislation also give CFIUS — which is an inter-agency, Treasury-led committee with nine Cabinet members, two ex officio members and members appointed by the president — authority to review any transaction involving foreign investments in US “critical infrastructure or technology companies”, even when they don’t involve the foreign entity acquiring a controlling stake. The act also expands CFIUS’s scrutiny to include real estate deals, mandating a review for any foreign purchases of property near US military installations, or sales of real estate located in US ports.

These are significant new powers for CFIUS, which was established in 1975, but gained increased traction after the September 2001 terrorist attacks. Even before the new law, CFIUS had the power to examine any takeover bid by a foreign company if deemed to pose a national security threat; intervene to change parts of proposed deals, for instance excluding part of a US firm from an agreement; and been able to negotiate with the parties to a proposed deal.

Of course, legitimate US concerns do exist about some overseas foreign investment. And the US is by no means the only country that is looking to modernise its powers in this area.

For instance, European policymakers in Germany, France and the United Kingdom are also debating this topic as technological, economic and geopolitical changes mean that reforms to public powers to scrutinise investments on national security grounds may well be needed. Across these nations, governments are looking at the best way to combine a broadly open approach to international investment while having appropriate security safeguards.

Compared to these European powers, however, what is striking about the US approach is the degree to which China has been singled out by Washington policymakers. So much so, that some in Beijing already perceive the new US legislation is just the latest part of a wider, grand strategy under Trump to thwart the nation’s rise as a global superpower.

In this context, any increased US veto of foreign investment and mergers could therefore see China — and indeed other countries — respond in a like-minded way. While increasing protectionism through tariffs and tougher security probes of foreign investment is easy to initiate, this can be difficult to control and unwind and it remains highly unclear if the latest US actions will fundamentally modify China’s policies, or simply trigger a further deterioration in bilateral relations.

While markets appeared to believe a breakthrough was possible in the talks, this was always optimistic in the current context. However, given the incentives that both sides have to eventually resolve the escalating economic disputes, a roadmap could yet emerge this autumn to help resolve them that may potentially require the personal intervention of Trump and Xi when they are next scheduled to meet face-to-face in November.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.