Turkey evolves into a one-man show

Ankara’s system of government was formerly admired by Western democracies as a model to be emulated, and its departure from democratic values has strained relationship with the EU

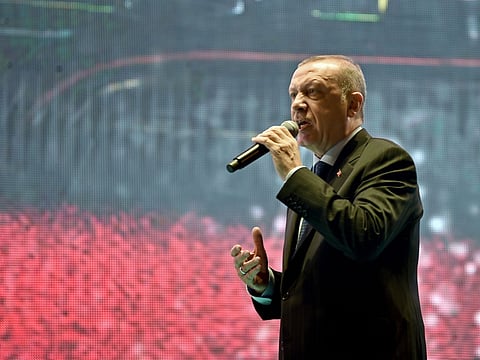

In light of the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s executive power grab albeit with the approval of 52 per cent of the country’s population, can Turkey still lay claim to being a democratic republic based on the separation of powers?

Certainly its system of government formerly admired by Western democracies as a model to be emulated by other predominantly Muslim states has teetered away from democratic values over the past six years, which is one of the factors negatively impacting Turkey’s fragile economy.

The Turkish lira has slipped 17 per cent since the beginning of this year due in part to investor concerns that the central bank has lost its independence to set interest rates. Inflation has ballooned to 15 per cent. Borrowing is said to be unsustainable.“Turkey’s economy is so hot it may face a meltdown” reads a recent headline in the New York Times, seconded by the Washington Post that predicts the nation is “headed for a big crash”.

On Friday, Fitch Ratings announced it had reduced the country’s sovereign debt rating to BB from BB+ citing deteriorating “economic policy credibility and “heightened uncertainty” caused by “initial policy actions following elections in June”.

One of those troubling actions was Erdogan’s appointment of his son-in-law Berat Albayrak as Minister of Treasury and Finance, a move that has not only been criticised as nepotistic but also slashed a further three per cent from the currency’s value.

Erdogan’s 15-year-long leadership style has always tilted towards the authoritarian supported by his millions of devoted followers but since constitutional changes have came into force his word is virtually law. Most checks and balances faced by democratic leaders have been erased.

The post of prime minister has been abolished and the president’s new responsibilities via nine newly minted offices encompass all institutions. Ministries, judicial and prosecutorial appointments, the military, intelligence services, the vetting of journalists and the state budget are all under the control of one powerful individual. According to Abdul Latif Sener, a former deputy prime minister, “there is no constitutional mechanism to change the government”.

Besides Turkey’s economic woes, personal freedoms have been substantially diminished, not least the freedom to protest and exercise free speech. Since the attempted coup two years ago over 160,000 people have been imprisoned and purges are still ongoing, the latest involving 18,000 state employees, the majority members of the police, the military and the teaching profession accused of having links to terrorist groups.

More than 1,000 companies have been sequestered by the state. Some 320 journalists have been arrested; 130 media outlets have been shut down. Protests are dealt with severely.

On July 6, four university graduates were arrested in Ankara accused of defaming the president. They were accused of defaming the president over a banner emblazoned with cartoons with the words “The World of Tayyip”.

Turkey’s departure from democratic values has strained its relationship with the EU, currently considered to be a marriage of convenience based on mutual interests. Last year Erdogan angrily told the EU to “stop leading us by the nose”. “If you want to take Turkey into the European Union just tell us, do it. When you do not want it, tell us,” he said.

An EU report published in April appeared to scupper Turkey’s accession chances. It slammed mass arrests, corruption, a lack of freedom of expression and human rights abuses. Turkey is taking “huge strides away” from the European Union said EU commissioner Johannes Hahn at the time.

In June, the EU indicated Ankara’s hopes were deadlocked while asserting Turkey was one of the bloc’s important partners due to its role in preventing migrants from crossing the Mediterranean. In that respect Turkey holds Europe over a barrel threatening to open the gates if the EU does not institute visa-free travel for Turks.

Nevertheless, the country’s Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu confirms that Turkey’s strategic goal is to progress to EU membership although in truth as one poster on social media put it, Erdogan “has as much chance of winning the lottery”.

Linda S. Heard is an award-winning British political columnist and guest television commentator with a focus on the Middle East.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox