The situation in Libya just got a whole lot more complicated

The international community has been scrambling for a political solution to the Libyan crisis for several reasons

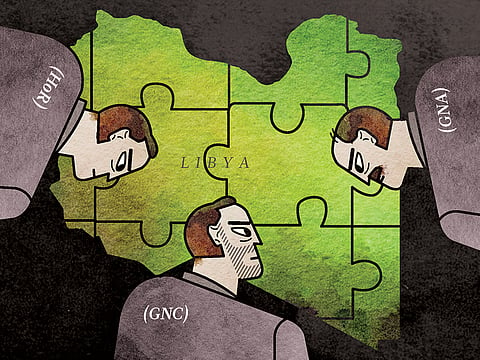

Libya now has three competing governments — up from two a month ago — thanks to further interference from foreign powers.

The first foreign intervention in Libya, in 2011, had only the removal of former leader Muammar Gaddafi and securing the country’s oil as aims. There was no plan for post-Gaddafi governance and little understanding of the complexities of the Libyan social order. Furthermore, having taken up arms to rid themselves of the dictator, hundreds of thousands of men are now reluctant to put them down… or certainly not until there is some semblance of consensus, peace and order. As a result, around 2,000 heavily-armed militias are operating across the country, battling for resources and influence; Libya’s entire population is only six million.

The political situation is equally chaotic and just became more so.

Until April 7, Libya already had two rival governments. The internationally recognised, elected government, known as The House of Representatives (HoR) was forced to flee Tripoli in August 2014 when Libya Dawn, a key pro-Islamist militia umbrella, seized the airport and ensconced an Islamist-led Government of National Congress (GNC), headed by Khalifa Ghweil. Meanwhile the HoR parliament relocated to a 1970s hotel in Tobruk, in the far east of the country where Islamist militias hold sway, and announced it was ‘business as usual’. The HoR is backed by General Khalifa Haftar’s ‘Libyan National Army’; Haftar is a divisive, CIA-trained military man with lofty ambitions of his own.

Under pressure in Syria and Iraq, Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) has found fertile new pastures in Libya’s chaos and now controls most of the coastal region — which is also abundant in oil.

The international community has been scrambling for a political solution to the Libyan crisis for several reasons: a working, western-friendly, central government is essential to lead the fight against Daesh and operate the essential machinery of the country’s economy — the National Oil Corporation (NOC) and the Central Bank of Libya (CBL); in addition, the anarchic situation on the coastline is facilitating the lucrative work of the people smugglers (which Daesh has largely seized for itself) and has obvious security implications for Europe, just 300km across the Mediterranean.

UN-brokered negotiations involving representatives of both the GNC and the HoR, which lasted for months in the Moroccan town of Skhirat, eventually produced the Libyan Political Agreement which was signed on December 17, 2015, and appeared to have produced a new unity government — the Government of National Accord (GNA) — with Fayez Sarraj, a businessman with little political experience, and in exile in Tunisia, as prime minister. The expectation was that, once properly ensconced, Sarraj would call for foreign help to train a new Libyan Army and confront Daesh. In other words, legitimise another foreign intervention, just as the first was endorsed by UN Security Council resolution 1973.

But it seems foreign powers have been operating in Libya for some time already.

A leaked memo from a confidential briefing given by the Jordanian King Abdullah to US congressional leaders revealed that around a thousand British SAS soldiers have been deployed in Libya since January, and that Jordanian special forces are embedded within them. King Abdullah, the country’s ruling monarch, has long been a devoted ally of the western powers and he is richly rewarded for his loyalty — last February, US President Barack Obama handed him $1 billion (Dh3.67 billion) aid to combat terrorism and house the 800,000 Syrian refugees who have found sanctuary in Jordan.

Special forces centre

The king is also keen to make Jordan a centre of excellence for special forces. He trained at Sandhurst in Special Operations and has told me personally that he is very proud of this.In addition, he has a personal vendetta against Daesh, who brutally burned alive the Jordanian pilot Muath Al Kasaesbeh. When the video of this atrocity was released last February, the king swore revenge, as did his head of the Armed forces.

The British government has denied King Abdullah’s claim, admitting it would necessarily endanger military personnel on the ground. British Prime Minister David Cameron would not have been obliged, in any case, to gain parliamentary approval to deploy SAS personnel as they are not considered part of the conventional army.

Assuming that the king is not lying, and it is my belief that he is not, the deployment was likely related to the March 30 arrival — by sea — of Sarraj and six members of the Presidential Council in Tripoli. The foreign forces, working with local militia, may have been seeking to investigate and, if possible, improve, the security situation ahead of this defining moment in post-Gaddafi Libya. Unlike the GNC and the HoR, Sarraj has (for the moment at least) the backing of the Libyan Investment Authority, National Oil Corporation and the Central Bank, which holds the nation’s purse strings — just the sort of friends the West would like to share. A few days later, the ambassadors of Britain, France, Italy and Spain arrived in Tripoli to offer their support for the new government with the optimistic Spaniard declaring, “We are very close to normality, very close to peace”.

Unfortunately, the two rival governments already in place have now refused to acknowledge Sarraj as the country’s new leader. Sarraj was obliged to travel to Tripoli by boat because the GNC would not allow him to fly and his advent was heralded by explosions and gun fire around the city. Nor has he been able to advance beyond the confines of the naval base, where he has now set up GNA operations. Only the day before Sarraj arrived, Ghweil had agreed to step aside in the interests of national unity. Now, however, he is threatening to jail anyone who works with the GNA.

And then there were three… or four, if you also count the vigorous bids for power by Daesh. Unsurprisingly, the news this week has been that Sarraj’s planned request for international help has now been postponed, presumably because his tenure is so very precarious.

Little wonder that Obama refers to the Libyan intervention as, “the worst mistake of my presidency”.

Abdel Bari Atwan is the editor-in-chief of digital newspaper Rai alYoum. He is the author of The Secret History of Al Qaeda; A Country of Words, his memoirs; and Al Qaeda: The Next Generation.