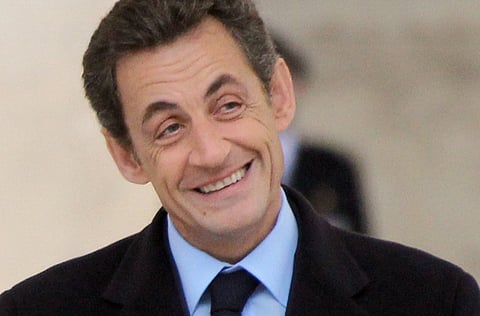

The Sarkozy circus

Lurid gossip about the president's marriage spiralled into a political scandal

It's a farce straight out of Molière — with a few twists even he might have rejected as too far-fetched. What started with vague rumours of marital infidelities involving the French president and his pop-star wife has snowballed into a political mess, involving inquiries by the police and intelligence services, the banishment of advisers, the smearing of a former justice minister — and, of course, dastardly plots by wicked Anglo-Saxon financiers.

Welcome to "Le Château", as the Elysée Palace is now known to French satirists, home to Nicolas Sarkozy, Carla Bruni-Sarkozy and their cadre of highly influential — and occasionally hysterically ineffectual — advisers.

The story began with those online rumours, which appeared on Twitter shortly before the regional elections in which Sarkozy and his centre-Right UMP party suffered a drubbing. They claimed that the president's wife was having an affair with a fellow pop singer, while Sarkozy had sought consolation in the arms of a married junior minister (and karate champion). The story was picked up by a blog on the website of Le Journal du Dimanche, a respected Sunday newspaper, and seized on by the foreign press.

Given the lack of evidence, and robust denials all round, Sarkozy could simply have laughed the whole thing off. But this president doesn't get jokes: he gets even. First, he reportedly "pressured" the paper, which is owned by a friend of his, into removing the blog. Two journalists were then summarily fired. France's domestic intelligence agency was ordered to pursue the culprits; Le Journal du Dimanche also filed a criminal complaint, sparking a separate police inquiry into the "introduction of fraudulent information into a computer system".

Pointing fingers

Enter, stage left, Sarkozy's spin doctor, Pierre Charon. All this could be a calculated plot to destabilise the president before the elections, briefed the portly Alastair Campbell à la française, who promised a campaign of "terror" against the rumour-mongers (despite his own reported proclivity for gossip). The potential culprits suggested ranged from the opposition Socialists to the president's arch-rival, former prime minister Dominique de Villepin, to British financiers, bent on stopping Sarkozy from pushing for stricter regulation of the City at next year's G20 meeting.

Charon, however, ended up by blaming Rachida Dati, 44, France's Dior-loving former justice minister. Once a protégée of Sarkozy and his second wife, Cécilia, she had been ousted from the Cabinet and exiled to Brussels as an MEP, where she had complained that she might die of boredom. She was stripped of her bodyguards, chauffeur and official car — only to protest her innocence and threaten to sue for slander.

The head of the domestic intelligence service denied that Dati's phone had been bugged and insisted he had called off his investigation once the police started theirs. Enter a second Elysée aide — Claude Guéant, Sarkozy's chief of staff, also known as "The Cardinal". "The president of the Republic no longer wishes to see Rachida Dati," he told one newspaper. The next day, however, he suggested cryptically that "yesterday's truth is not, perhaps, that of today".

Subsequently, the Elysée has tried to damp things down: in a poised radio interview, Bruni-Sarkozy declared the rumours "insignificant". "There is no plot," she insisted. "There is no vengeance. There is nothing. We have turned the page." Dati, she added, remained "very much our friend".

But to return to Guéant's words, the French are now asking themselves whether "yesterday's truth is that of today" when it comes to Sarkozy himself.

The president is fighting back. On Tuesday, he banished many of his advisers, including Charon, from his daily meetings, and hopes a landmark reform of the pension system will help claw back support ahead of his chairmanship of the G20 next year.

But some wonder whether it will make any difference. One columnist in Le Monde last week quoted Jacques Pilhan, a wily adviser to two former presidents: "To speak when one is unpopular is like walking in quicksand. The more one jiggles about, the more one sinks."

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox