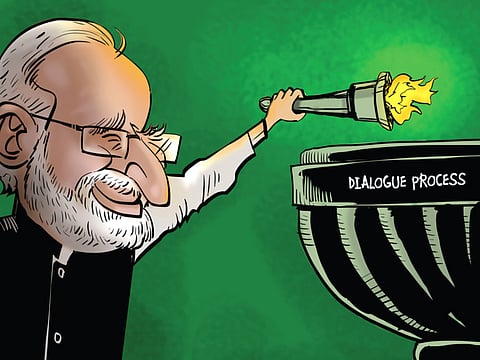

Pakistan trip: Advantage Modi?

A stabilisation of relations marked by a slow upward progression as the dialogue process begins is what the peoples of the two countries can hope and press for

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s surprise visit to Lahore was viewed by some in Pakistan as a public relations move with the advantage going to him. Was it against the recent run of play in bilateral relations between the two countries; and where if anywhere will it lead to? These questions deserve more attention.

Since the BJP government took over the reins of the government in India, relations have been troubled despite initial expectations when Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif controversially accepted the invitation to attend the new PM’s inauguration last year. Even before he left Delhi the Indian spokesperson labelled the congenial meeting between the two leaders a lecture for Pakistan to control terrorism. That set the tone. Firing incidents flared across the Line of Control in disputed Kashmir accompanied by belligerent statements from the Indian side.

When meetings to revive the dialogue process were fixed, umbrage was taken that the visiting Pakistani officials wanted as before to meet Kashmiri leaders. India’s emphasis that the talks would centre only around terrorism was not acceptable to the Pakistani side that was determined to bring up Kashmir and all other disputes.

Pakistani officials assessed that despite Sharif’s determination to build better relations with India riding high on its economy, its strategic and conventional military strength bolstered by the US, its western allies, and Russia gave no such reciprocal priority to a neighbour it considered beset by terrorism and temptingly vulnerable to external destabilisation. Indian officials alleged that while the government wanted better relations the Pakistan military was opposed to it. An inauspicious situation which appeared to be gridlocked.

Then, on the margins of the Climate Conference in Paris on November 30 this year the two prime ministers appeared to meet by chance and sat down for an “impromptu” chat. One can assume that this was not unplanned ; and that the two leaders had a variety of channels beyond their diplomats to exchange views on how to break the deadlock.

Ensuing events tend to bear this out. On December 6, the two National Security Advisers along with the Foreign Secretaries met in Bangkok with the media informed subsequently. On December 8, Indian Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj attended the Afghanistan-centric Heart of Asia conference in Islamabad and held talks with Sharif and her counterpart. Both sides agreed to restart the dialogue process now termed the Comprehensive Bilateral Dialogue covering Peace and Security, Confidence Building Measures (CBMs), Jammu & Kashmir, Siachen, Sir Creek, Wullar Barrage/Tulbul Navigation Project, economic and commercial cooperation, counterterrorism, narcotics control and humanitarian issues, people to people exchanges, and religious tourism. To complete the circle Modi following the inaugural ceremony of the new Indian-financed Afghan Parliament building in Kabul asked if he could a few hours later, enroute to Delhi, drop by to see Sharif who was in Lahore. He was welcomed and warmly received.

Dialogue process

The last visit by an Indian prime minister to Pakistan was by BJP leader Atal Bihari Vajpayee who attended the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (Saarc)Summit in January 2004. As coordinator for that conference, I witnessed that unprecedentedly no calls by the Indian prime minister on then President Pervez Musharraf or then Prime Minister Zafarullah Khan Jamali had been requested. Only after the conference began were these requests conveyed.

That visit in 2004 set in motion the dialogue process which in fits and starts has defined the objectives of both countries since then. Ironically in the intervening years then Congress Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, despite wanting to, was unable to visit Pakistan. This surprise visit to Lahore, though not a state visit, is a significant event and while the initiative was taken by the Indian prime minister, both leaders behind the scenes were responsible for making it possible. The advantage accrues to both countries.

How far will they take this advantage, and where will it lead? If there are any two countries that need better relations, at the very least stable relations, it is Pakistan and India: two nuclear neighbours with significant portions of their population beset by poverty. It would be unrealistic to expect any dramatic or sudden shift. A stabilisation of relations marked by a slow upward progression as the dialogue process begins is what the peoples of the two countries, the region, and indeed the international community can hope and press for.

Both countries need to address all their disputes through talks, and both need space to address internal issues. Probably the first step will be to tackle the low hanging fruit: liberalising the visa regime for more people to people contact; speeding up the repatriation of civilian prisoners held up by identity issues; giving special ID cards to fishermen who are frequently picked up for straying, restoring sporting links; reactivating the Joint Judicial Commission to meet periodically to address some of these issues; and a meeting of the two directors general of military operations (DGMOs).

Both governments will have to make an effort to dilute the hostility of the media. Pakistan for its part should endeavour to regain in India a constituency for better relations. Just reviving pre-1954 24-hour visas to visit Lahore would make a significant contribution. In the dialogue process extending both nuclear and conventional CBMs frozen since 2007 will need further building on, and there are certain near-agreements that merely need finalisation. Better relations would improve the pace and prospects of the recently reactivated TAPI gas pipeline, and in turn constitute a regional CBM.

For both countries to move forward, addressing internal doubts and caution will be as complex and crucial as dealing with each other.

Ambassador Tariq Osman Hyder is a retired Pakistani diplomat.