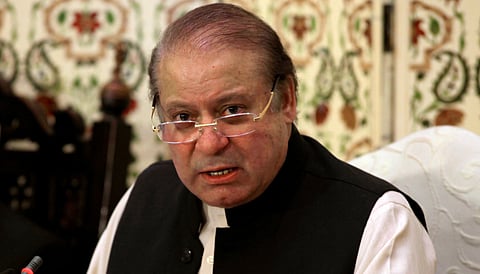

Nawaz Sharif jeopardising Pakistan’s future

Though it is convenient to blame the army, it has shown no sign of interfering with the political process and yet the former prime minister continues to fulminate against ‘unnamed forces’

Former prime minister of Pakistan, Nawaz Sharif — facing serious criminal charges and now a victim of his own delusions — continues his rants against the superior judiciary and “the unnamed forces”. In the process, Pakistan is fast sliding into an anarchic state.

Known for his combative style and insecurities, his idea of the prime minister’s role and power is akin to the 19th century Rana prime ministers of Nepal, where the hereditary post, with absolute power, passed from father to son. Just like the important positions remained within the Rana family and its different layers, depending upon their importance, power during Sharif’s premiership has remained confined within his narrow family and his courtiers.

Nawaz, the eldest child in a strictly patriarchal family, grew up under his father’s shadows. His urge to enjoy freedom of action, often exercised by his smarter younger brother Shahbaz Sharif — the Punjab Chief Minister — remained suppressed under the strict family values. Pakistan’s worst military ruler, General Zia-ul Haq, had launched him into politics as the army’s front man. Conspiratorial by nature, he has destabilised every civilian prime minister since Zia’s time, beginning the 1980s.

Every time he has been in power, Nawaz has been sacked, chasing unbridled authority and for his inability to play as a team member. The constitutional separation of power between the three branches of the government — the executive, legislature and judiciary — has held no meaning for him. He is yet to comprehend that statecraft requires compromises through inputs from various organs of the state. Operating through his family and cronies, he has left all state institutions dysfunctional and weak. Rarely showing himself in the parliament, he made it ineffective. The Cabinet met barely four to five times a year during his four-year rule. Democracy to him and his compatriots means winning elections only. Little does he understand that democracy means transparency, rule of law, responsible governance and accountability. He considers himself larger than the state institutions.

Now, when the Supreme Court disqualified him from holding any public or party office in Pakistan, Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), the oligarchic party, amended the law through the force of its majority in the parliament, allowing even a disqualified person to hold party office. Ironically, Nawaz wants to become a kingmaker and rule through proxies, denting democratic values in Pakistan. He has, therefore, chosen to put his interests before that of his country. As he is now being tried for serious criminal offences under the Supreme Court’s orders, the ministers often act as opposition politicians, criticising state institutions.

Three main reasons have been identified for the troubles the Sharif family is facing now. Pakistan, for which the credit must go to General Pervez Musharraf, has a fiercely independent and unforgiving media that is free to report corruption stories. In fact, much of Nawaz’s ‘probing’ took place on prime-time television programmes, than in the actual court rooms! Most of it is born out of a feeling of extreme disgust at the way the Sharif family has lied to the country and judiciary and then claimed victimhood. Except for the party loyalists and Nawaz’s courtiers, no one believes them. The media and the power of the civil society now act as major barriers to his quixotic ambitions.

Second, after decades of corruption, cronyism and misgovernance by the Pakistan Peoples’ Party (PPP) and PML-N-led governments, the 2013 election saw the entry of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf PTI), led by the charismatic cricketer-turned-politician Imran Khan. Securing the second-highest number of votes, PTI emerged as a credible alternative force on the political horizon of the country. Known for his tenacity, Imran has single-handedly led the drive against corruption, compelling the Supreme Court to step in and deal with the issue, leading to the trials and Nawaz’s subsequent disqualification.

Third, since the political parties and civil society came together in 2007 to reinstate the then chief justice of Pakistan, who had been deposed by the then president Musharraf, the judiciary has acquired new muscles, which most Supreme Court judges continue to flex. Nawaz, who reportedly bought out or engineered the ouster of judges finds it aberrant to stand in as an accused in criminal cases that could possibly lead to fines, imprisonment and life-long bans on him and his family to hold public offices.

Though it is convenient to blame the army, it has shown no sign of interfering with the political process and yet Nawaz continues to fulminate against “unnamed forces”. Following the ‘Panama Leaks’, he continued to lie to the public and the parliament and when it came to the courts, he presented the clumsiest defence of his family’s ill-gotten wealth.

His party, reeling under a series of legal setbacks, now faces the challenge of maintaining party unity. His attitude, his rantings and those of his close aides have resulted in a systemic crisis, which the country could well do without. How long will the army’s patience be tested is now the million-dollar question.

Nawaz is now seriously jeopardising Pakistan’s future.

Sajjad Ashraf is an adjunct professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore. He was a member of Pakistan Foreign Service from 1973 to 2008 and served as Pakistan’s Consul General in Dubai during the mid 1990s.